Insight into the Humanities: A Conversation with Bernie Ferrari

Insight into the Humanities: A Conversation with Bernie Ferrari

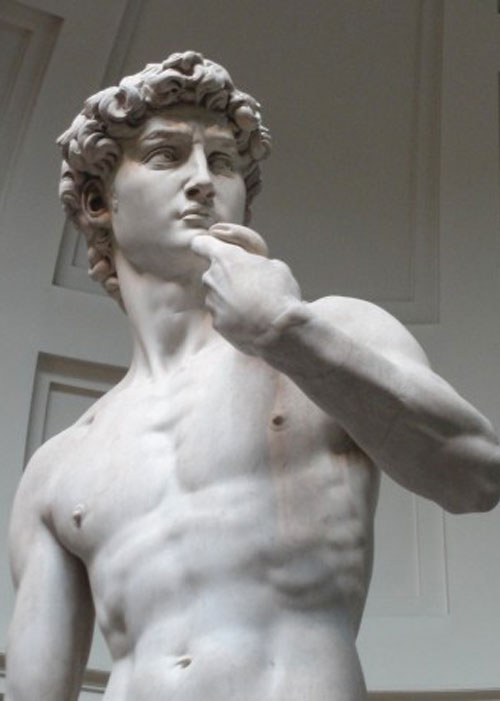

Every year, University of Rochester Trustee Bernard (Bernie) T. Ferrari ’70, ‘74M (MD) spends 30 minutes with David. Michelangelo’s David, that is. He halts there and looks up in wonder at this eloquently cut 5.5 meters of block marble at the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy.

Linda and Bernie Ferrari

“I stand there and ask myself how this was done by a 26-year-old man so long ago,” he says. “It gives me perspective into the human spirit and insight into the possibilities of what we can do.”

Ferrari’s passion for the humanities runs deep. “Literature, music, the arts—all of the humanities—help give our lives meaning,” he says. “We need them in our lives.”

As a science major and then a medical student, Ferrari’s University days were full of classes, required readings, and countless labs. He didn’t have much free time, nor the space in his schedule to take many humanities classes. But, the ones he did take sparked his curiosity and interest. He recalls memorable courses in architecture and film, and spending time in Rush Rhees Library where on Friday evenings he would listen to elegant string quartets.

Having just announced his retirement from Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, Ferrari talks about time, and what defined different periods of his life. “When you become a physician and then a surgeon, every second is taken. It’s only later that you can carve out time for yourself. For me, interest in the humanities began in high school and then grew in college. They provided a respite from the intense course of science and medical study. And now, I can discover anew what they humanities bring to the surface of life, which is beauty.”

Both Ferrari and his wife, Linda, have a deep appreciation for the Renaissance—an intense period of cultural, artistic, and political rebirth in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. It’s when a movement called humanism was born in Italy. “Linda and I are incredibly intrigued that such a small peninsula during a relatively short span of time could produce so many geniuses.”

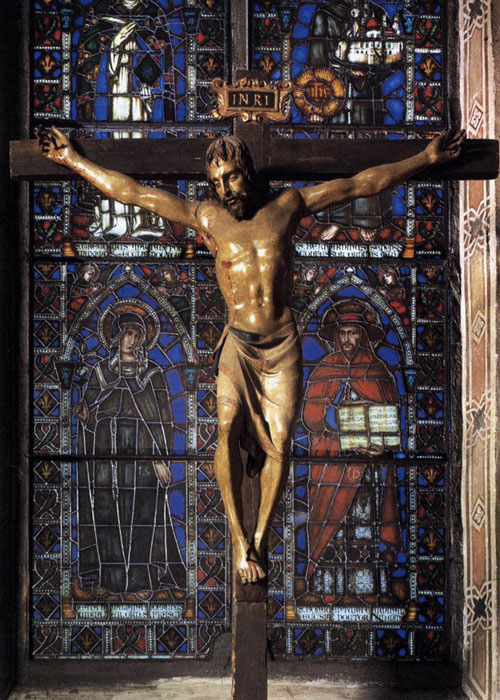

The output and productivity of the Renaissance is a bit mind-blowing for the Ferraris. “From Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore to Michelangelo’s David to Donatello’s crucifix of Santa Croce . . . we look at this incredible array of humanistic creativity and wonder: how did this happen?”

That wonder fuels the Ferraris’ deep commitment to the humanities. They both recognize the value of preserving research that can inform our collective humanity. For them, the faculty who conduct humanities research are paying an important service to the world, and providing a lens through which to see it.

“Conducting research in the humanities is like looking in the rear view mirror of history, to see what man can accomplish,” he says. “But, it’s even more than that. The humanities help us determine the angle and aperture of the windshield, tint it, and even redirect it to allow us to ask questions about our future and our present in ways we might not ask otherwise.”

Ferrari gives the example of Niccolò Machiavelli, often called the father of modern political science. In thinking about Machiavelli, Ferrari references Christopher Celenza, is a Georgetown dean and professor and who served two years ago as a Symposium invited speaker. “Celenza writes extensively on Machiavelli and what his contributions mean to us today. His research helps us think about leadership, and he tees up excellent questions. All of the dusty library hours Celenza has spent on his research have contributed volumes of insight into today’s society.”

The Ferraris’ philanthropic commitment to the humanities at the University emphasizes their vital role. “In today’s world, especially in higher education where so much of the emphasis has turned to preparing students for specific jobs, it is most important to preserve the humanities,” he says. “In our view, the humanities cannot become victim of the yearly, and even daily, realities of budget limitations. They are too important.”

“All jobs require the skills they offer and the beauty they bring to our lives,” he adds. “We need endowments like these to forever protect them and to provide, on small and large scales, a foundation off of which they can grow.”

Learn more about this year’s Ferrari Humanities Symposia here. Read about the most recent gift from the Ferraris here.

—Kristine Thompson, April 2019