Art and Art History

Voyeur & Violator: The Obscene Narrative in Early Modern Italy

Spring 2024, Volume 22, Issue 2

Daniel Heberle ’24, Christopher Heuer*

I dedicate these lustful pieces to you, heedless of fake prudishness and asinine prejudices that forbid the eyes to gaze at the things they most delight to see. What harm is there in seeing a man mounting a woman? – Pietro Aretino, 1537[1]

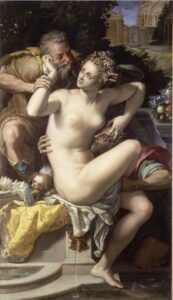

Hands caress the curled, ribboned hair, grapple onto her arm, and search in between the thighs because the elders have finally coerced Joakim’s chaste wife into having their way with her. She does not look frightened or scared, but rather optimistic. The woman gracefully holds onto the man’s face and holds the crown of the man’s head beneath her, continuing his search between laced fabric and flesh. Alessandro Allori’s Susanna and the Elders (Fig. 1) reads closer to Pietro Aretino’s obscene Sonetti Lussuriosi than a scene depicting feminine defiance against the elders who lust after her, canonically failing to violate her. Decades before the heroine Susanna of Artemisia Gentileschi, the painted and engraved Susanna sat in between the violators; the painted figures or internal viewers within the paintings of Renaissance Italy and well into the Baroque, and the voyeurs; the external viewers, who ogle before the work. Moreover, the relationship of viewing the female nude body from the perspective of the elders, and that of an awareness of the viewer’s role in these acts of sexual violence, reflects a transgression in the conception of the obscene narrative, and in the reception through both painted figure and the early modern viewer in sixteenth century Italy. Outside these images lie the obscenities of Renaissance visual culture such as Marcantonio Raimondi’s I Modi, engravings after drawings by Giulio Romano and Aretino’s Sonetti.[2] During the period in which these works were created, the holy and the sinful were circumscribed by careful distinctions between the permissible erotic-nudity and the tasteful display of sexual intercourse, and the obscenely erotic-sexual content that threatened a centuries-long established decorum of how to depict nudity and intercourse in art. As a result of erotica in the Renaissance, and the connotations to antiquity and the pursuits of pleasure beyond the teachings of the Church, paintings and prints depicting the Book of Susanna fluctuates between the physical interaction and the purely visual observation.[3] This specific narrative scene reveals the troublesome relationship between a secularized erotic visual culture alongside the didactic artistic programs issued by the Church at the time of the Council of Trent and afterwards. Further, considering the history of critical approaches to the rational and functional roles of the painters, the viewer’s position in the work becomes dependent on a retrospective understanding of the narrative and whether or not to victimize Susanna, or to join the elders in objectifying the nude wife.

Figure 1. Alessandro Allori. Susanna and the Elders. 1561, oil on canvas, 202 x 117 cm, Musée Magnin, Dijon, France.

Alessandro Allori’s approach to the scene radically alters perceptions of the beholder’s innocence in the face of other, albeit later Italian examples such as Domenichino’s Susanna or the Prado Guercino. Allori chooses the direct, confrontational, and hallucinatory route of perception via Mieke Bal’s elucidations of the elder’s internal intentions, and their actions actualized by their threats, whereas other artists opt for a passive, looking mode of contact between the elders and the unknowing Susanna. Additionally, the treatment of expression, gesture, and physical contact radically alters the passivity or active engagement, and perhaps indulgence, in the depiction of sexual violence. The obscenely erotic nature of the visualized Susanna narrative presents a unique problem in the realm of painted biblical narratives because of the extratextual nature of its depiction––an extratextual accessibility of this kind uncovers the severe extent to which narrative scenes can be lead astray from the safety of iconographic accuracy. The structural relationship between the male painter, the male gaze, and the reception of the decent and obscene erotica during the early modern period may also contribute to the nefarious appearance of Renaissance and Baroque renditions of this scene. [4]

It may seem strange to consider the sexual charge of the Susanna imagery without first mentioning the larger presence of the erotic within the early modern Christian world. Without delving into how the susceptibility of eroticizing the image functions, more on this later, there have been numerous instances where the religious image has inspired tremendous sensations within people. During the fourteenth century, one anonymous author encouraged Dominican nuns to “[i]magine the Lord […] disrobed for your sake, so that he might rest beside you naked.”[5] One century later in 1427, Saint Bernardino recounts that someone “defiled himself” while standing before a cross, contemplating Christ.[6] These among other instances show an unusual boundary between the devotional and the perverse. Christ can be imagined lying disrobed beside nuns and prayer can even be transformed into a moment of pleasuring the self. Moreover, the very visual representation of figures in paintings become objects, or sites, of inflamed desire. Vasari gives the potent example of Fra Bartolommeo’s St. Sebastian, which “gave rise ‘to light and evil thoughts’ among female parishioners” when they were in confessions.[7] Centuries before the Modi, viewers did not need to be inundated with the severely erotic since patrons and worshippers understood how to exercise pleasure out of the unforeseen locations of the religious artwork.

When it comes to understanding what exactly is explicit and transgressive about the Susanna imagery, per Bette Talvacchia, we should hesitate to label these images “pornographic” due to anachronistic concerns with applying the term to early modern images.[8] With the nineteenth century lineage of the word coming into use during the excavations of Pompeii, Talvacchia looks instead to the binary of “onesto/disonesto” used by Vasari and his contemporaries pertaining to conventions of erotic imagery, explicitly regarding the Modi but which can extend to the Susanna imagery.[9] It is important to remember that while the Modi predates the Council of Trent and provides significant insight into the opinions of visual erotica, Allori’s Susanna dates to the final years of sessions. This time period spanning between the Modi and Allori’s Susanna is exceptionally peculiar in the treatment of visual erotica. In 1539, Girolamo Romanino completed frescoes at the Magno Palazzo for the Tridentine Cardinal Bernardo Cles.[10] What was evidently treated as a comparison between Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling painted some decades earlier, Romanino’s ignudi exhibited their bodies, “with decency […] in most cases the twisting postures are calculated to conceal the genitalia”, which was received by the Sienese doctor Pietro Andrea Mattioli in a poem about the frescoes as Romanino’s ingegno, and in turn his onestà.[11] Here, the erotic is balanced, and well received through Mattioli’s poetry, and does not cause a stir. For the early moderns, visual erotica was not necessarily problematic since it was viewed as either decent, “onesto“, or what could fall under obscenities, “disonesto“.

Mentioned earlier, the most potent and infamous example of the obscene artwork in sixteenth century Italy: Marcantonio Raimondi’s series of 16 engravings after Giulio Romano, I Modi, serves as a touchstone for printed visual representations of sex in papal Rome around 1524.[12] Moreover, the Modi remains the most thoroughly researched series of erotic imagery in sixteenth century Italy, in the present day, and concerning early modern criticism against obscene imagery. Through the Modi, among other examples covered herein, we can assimilate early modern reception onto Allori’s creation. The series is unique for the complete deviation from a mythological or biblical narrative, it is rather a fixation on continuously changing positions, possible and impossible, in sexual intercourse.[13] This deviation from narrative may confuse the possible relationship to the Susanna imagery, but a closer look into the implications and experimentations of how to depict sex accomplished through I Modi may situate us in a position to understand Allori’s ulterior motive in depicting Susanna and the Elders.

A few years after the scandal of Raimondi’s jailing by Clement VII and the order to destroy all prints and plates to produce the series, a series of woodcuts after Raimondi’s engravings, accompanied by poetry, were printed in 1527 by Pietro Aretino, called the Sonetti Lussuriosi (Salacious Sonnets). [14] The Modi fixates on the interaction between man and woman for the pure pursuit of pleasure, disregarding previous Christian discourse on the hierarchies of position and reasons for intercourse, “licit only under certain conditions and when done in certain ways.”[15] The original positions may have been sketched out by Romano, “on the walls of the Sala di Costantino in a state of pique against Clement VII,”[16] uncovering the nefarious relationships between notable courtesans with members of the papacy.[17], [18] The pope’s government occasionally made rulings regarding printed images; one famous instance concerns a privilege obtained by Ugo da Carpi for a chiaroscuro woodcut, granted by Pope Leo X in 1518.[19] Printed text in books were subject to censorship as recalled by Lodovico Dolce in his Dialogo della pittura, “the law prohibits the printing of immoral books,” however, the engraved or woodcut image was considered a separate and less important matter.[20] Thus, the censorship of the Modi is considered “the first time the Lateran ordinance was applied against printed images.”[21] Although the censorship of Raimondi’s Modi was evidently effective, Aretino’s Sonetti containing the woodcuts would become famous for its brusqueness, the depiction of Raimondi’s lost work, and the written dialogues Aretino constructs between the figures in the images.[22] The indulgence of the erotic printed on the pages of the Sonetti are at the same time the efforts of Aretino to tarnish the reputation of papal Rome after almost being fatally stabbed on July 28, 1525 by Achille della Volta, a member of Gian Matteo Giberti’s household, the datary to the Pope.[23] Moreover, the Sonetti are caught between the tensile papal politics and an unusual attention to vocalizing the silent imagery of the Modi.

Although it may be tempting to fixate on the formal aspects of the Modi, the few plates revealed to us through Aretino’s woodcuts in the Sonetti introduce an “old procuress” checking in on the courtesan and her client.[24] Aretino makes the old woman’s intentions explicitly obvious, “Ah, shameless pair! I spy you / On that mattress pulled down to the floor.”[25] The window itself is rendered as an opening to the outside world, albeit completely bare and left uncut save a single line to create the sill, and the old woman leans into the window with her hand gripping the ledge. A device not necessarily known to scenes of explicit content, besides the implications of voyeurism belonging to the iconography of Isaac and Rebekah and the spying Abimelech, or even Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, the window implies a distanced means of viewing erotic scenes as legitimated through the image itself. This addition to the engagements realizes the viewer’s position in relation to the scene, and also the position of an unseeable viewer that may lie beyond the window, out of our sight, thus making our presence in the scene resemblant of the visible procuress without having an occupational relationship to the courtesan with legs lifted and stretched. We must consider that before the Sonetti, Raimondi’s engravings were not ekphrastically rationalized or dramatized beyond their purely visual content. Before the Sonetti, the Modi were simply the “ways” or “positions.” While Raimondi’s series independently worked off of existent Venetian texts advertising and explicating the popular and eminent culture of courtesans in the sixteenth century,[26] Aretino gave a voice to the physically active, gesticulating and expressive figures.

The epigraph of this paper concerns a letter from Aretino to Battista Zatti, a surgeon from Brescia.[27] This remarkable document contains the first mention of the Sonetti by the author himself. Moreover, the Zatti letter contains highly intriguing elucidations about the importance of the phallus and its causal relationship to the creation of notable men from Italian history, along with the writer and the recipient.[28] After these pleasantries and praise of the phallus, Aretino engages in a fascinating exercise in the abject connotations of the hands and mouths of men:

Men’s hands might well be hidden since they gamble money, swear oaths, practice usury, make obscene gestures, tear, pull, punch, wound, and kill. And what about the mouth that curses, spits in the face, devours, and makes you drunk and vomits? [29]

Aretino makes a stern argument for the appreciation of the phallus which is always “hidden” and compares the hidden nature of the human anatomy with seemingly innocent bystanders of the stigmatized phallus. For Aretino, the hands and the mouth are far more guilty of the potential for not only ugliness but the violence and obscenity, ostensibly the sinfulness, than the phallus can produce, or be capable of. With this letter, we should consider that the pornographer intends to write in support of the sexual organs and that the Sonetti are not merely a playful interpretation of Raimondi’s engraved reproduction of Romano’s posizione.

Returning to the elders, one commonality shared between almost every depiction is the hands and mouth. Il Guercino deploys the gestural power of the hands to caution the viewer not to alert the bathing Susanna (Fig. 2). We are met with an elder’s gaze and furrowed brow, he knows we are also present from behind the bushes and thus participants in their spying. He points with one hand and pulls back the bush with the other allowing the other elder to look at their target. With a foreshortened, splayed open hand that breaches deep into the foreground, the other elder exculpates the viewer, telling us “[d]on’t disturb her” and “[d]on’t be so quick to judge us – wouldn’t you also be enchanted by her?”[30] From the letter to the Brescian surgeon, Aretino’s words accompany Guercino’s scene in a similar, appropriate manner as the Sonetti describes the Modi. Behind the bushes, hands “might well be hidden” from Susanna and these discreetly “obscene gestures,”[31] like the grasping of the erect and phallic staff, signal their nefarious intentions. Perhaps nowhere else in the history of biblical narrative scenes can the relationship between figures and viewer be so inherently problematic. While there are other examples such as depictions of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife, the viewer is the sole voyeur of the adulterous meeting. The story of Isaac and Rebekah spied on by Abimelech, famously painted by Raphael for the Vatican Loggias, contains another example of a third-party voyeur. However, Abimelech is always distanced from the viewer, looking down from a balcony. Though both parties view the adulterous pair, the complicity of the parties does not approach the ethically compromised criminal-accomplice relationship established and possibly encouraged by patron and painter.

Figure 2. Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, known as Guercino. 1617, oil on canvas, 176 x 208 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

What is particularly striking about Allori’s Susanna is the openness of the figure for the elders. There are no necessary signs of resistance to what the elders are doing. This is what Freedberg refers to as a “particular kind of exposure of the body” wherein Susanna gives herself to the elders, and to the viewer as well.[32] The exposure is gained in two ways: namely the mannerist, nearly impossible contortion of the torso where Susanna’s breasts are presented to the viewer, and the permission granted to the elder whose arm reaches in between her legs. Ultimately, this available bodily allows the “beholder”; whether the painted figure or the external viewer, to obtain a sensory-driven mode of exploration “in search of the sexual organs.”[33] One may argue that the Modi allows the viewer to reach this heightened state of visual and perhaps visceral arousal, and in some measures the similarities between the two types of images begets this comparison. The distinction between the latent narrative content found in the Modi, contemporary courtesans in the Vatican and the clever allusions to antiquity, and the presence of a known narrative from the Book of Daniel is crucial if we understand the significance of Allori’s rendering of the story. The openness of Allori’s painting sets the elders to receive what they desire, and arguably this image grants the viewer an otherwise unavailable depiction of the violated Susanna. In a moment of unprecedented painterly access, Allori provides the viewer with an improbable outcome that has thus been realized and set into action. This rare moment in sixteenth century Italian painting, where the eroticism of textual narratives is not displaced by some abstraction and distancing akin to the Modi; of nameless figures in ambiguous all’antica spaces. The eroticism instead provides the extreme ends of potentiality in inaccurately depicting biblical narrative scenes near the end of the Tridentine meetings.

As objet d’art, “the painted woman is also an object, available to the viewer’s gaze.”[34] As a Derridean parergon, the female nude rests on the borders between the artistic and the obscene.[35] Where the female nude figure is placed before the elder’s view, similar to how the viewer observes artwork in an exhibition space, a metaphysical condition is established between internal and external viewers. Guercino’s Susanna gracefully captures this condition where Susanna is displayed for the painted figures of the elders in the same way that Susanna is painted for the external viewer. This condition gives rise to Nead’s observation of a border. Addressing the border may clarify the objectifying depictions of Susanna in Allori’s painting. Because the combination of interaction and observation forms the erotic structure of not only the Book of Susanna, but also the visualized, albeit improvised text. While the Prado Guercino carefully balances on that border between art and obscenity, Allori’s radical approach topples over into the obscene. For not only do the elders get their way, but Susanna offers little resistance. Moreover, there also exists a border between looking and touching. When it comes to the voyeur, looking may be the primary and initial action, butut looking semantically infers the desire of touching.[36] Allori boldly crosses this border; in a discussion of a Domenichino Susanna (Fig. 3), Ellen Spolsky also notices this apparent crossing between what she considers the jumping “into that space in both picture and story where he [the elder] doesn’t belong.”[37] However, this crossing concerns a balustrade, and not Allori’s obscene direction of the elder’s hand from outer to inner thigh. Domenichino’s elder is making the attempt to reach the naked Susanna while Allori’s elder has been more than successful at achieving this goal.

Figure 3. Domenico Zampieri, known as Domenichino. 1603, oil on canvas, 56.8 x 86.1 cm. Galleria Doria Phamilj, Rome, Italy.

Within Domenichino’s work, and specifically Susanna’s upward gaze, Spolsky has argued that Susanna’s plea for divine intervention provides the ultimate weapon against the frail elders.[38] With the long history of physical weakness resulting in spiritual strength, the “imitatio Christi,” tracing back to Hildegard von Bingen,[39] the argument for Susanna’s complete innocence and chastity is shattered in the consideration of Allori’s perverse creation. Averse to the characteristic upward gaze towards God, Allori’s Susanna locks eyes with the elder. In Satisfying Skepticism, Spolsky makes an even more ambitious claim that the painter and the viewer retrospectively acknowledge Susanna’s innocence in an examination of works by Tintoretto and Anthony van Dyck:

By imagining and painting the moment of her instinctive resistance, the painter can both enjoy her unprotected powerlessness and can also attest her innocence as though he himself were the prophet Daniel […] Thereby, [Tintoretto and van Dyck] make themselves and the viewer into the Daniel who ‘sees’ the innocence of the woman and condemns the elders.[40]

Spolsky’s argument implies that the painter, within an epistemology of the text now visualized through painting, actively understands Susanna’s innocence at the level of judgment and justice already having been served through the text itself. She goes even further to state that the viewer also assumes the role of Daniel.[41] From the perspective of observation, Mieke Bal defines the situational relationship of the pornographer to the visual image as “not yet acting, they were ‘hidden and spying’.”[42] Whereas Spolsky appears to interpret the viewers’ viewpoint as one of Daniel ready to interrupt the elders before anything physical were to happen, Bal carefully recognizes the voyeuristic conditions of an unaware, bathing Susanna, and lustful old men waiting for the right moment to act. Allori’s approach is considerably pernicious to the argument Spolsky presents because it does not matter that Susanna is textually innocent when, in the moment pictorialized, her chastity may be breaking before the viewer’s eyes. In the space between her covered thighs and the elders’ “hidden” hands, Allori presents us with the ambiguity of Susanna defiled, or about to be. If the elders have gotten this far in this wildly extratextual depiction of the Book, then who is to say they will not carry out their rape after all? In a reading of the trial scene, Bal explicates that the elders’ description of the young man and his actions are the self-identification of the elders: “lying down with her is what they saw, hallucinating the fulfillment of their desire.”[43] This act of hallucination speaks to the potential not only of an imagined outcome of the interaction, but more importantly the visualized imagination brought forth by Allori, where their desire is becoming fulfilled.

When it comes to the potential for arousal with the Susanna depictions, we must consider the efficacy of erotic images and their shortcomings. David Freedberg contends that images showing “blatant sexual engagement” are most likely to fall short of arousing the viewer because they lack “the frission, the tension, or the still stranger arousal that arises from the sense of” images that border between the artistic and the unartistic.[44] The Modi for example, although incredibly scandalous for its time, should not perform as well as the Susanna imagery because it simply shows too much. Though the engravings represent images as Nagel refers to them “without any cover,”[45] stripped of any censoring of perverse acts, what should we make of the aesthetic and sensual image concealed once more? What Freedberg understands is that tension, of the just yet unobtainable, is the driving force of arousal. Unlike the Modi, the Susanna imagery is exceptionally effective as a transmitter of arousal because the elders rarely physically violate Susanna, save Allori’s painting. Even then, there are no cazzi or potta, only arms and discreet hands. Although the viewer understands Susanna’s ultimate innocence, the potential to hallucinate what “might’ve been” is evident with the presence of Allori. Susanna is not repelled by the elders’ actions, instead, she is magnetized to them. Opposed to the rhetorical features or “pastoral conditions” of the Greek romances the Susanna story emanates out of, we may conclude that Allori contemplates the possibility that no deus ex machina is coming to save the endangered woman.[46] How could Allori assume the perspective of Daniel if he were already too late? Alessandro Allori’s Susanna may perhaps be the most direct interpretation of this scenario, where there truly is no help on the way. These conditions strengthen the erotic tension possible in Susanna imagery because although other images are charged with sexual tension a la Domenichino’s “tugging contest” between the elder and Susanna,[47] or Guercino’s surveillant elders, they again do not cross the border between voyeur and violator.

Narrative scenes can inspire tremendous devotion from the viewer; the worshiper, and yet they can also inspire arousal from the same observer. In their potential for arousal, these paintings are threatening. The imagery of Susanna and the Elders creates unforeseen conditions of placing two viewers in contention with each other wherein the internal, painted viewers exculpate the external viewers standing before the painting. Though erotic art was understood and collected by the elite and literate nobles and intellectuals, an obscenely erotic art carries a volatility unlike other early modern pursuits. This volatility reached a breaking point in Rome emanating from Raimondi’s printshop with the printing of I Modi in the 1520s. Though Clement VII censored Raimondi’s reproduction of Giulio Romano’s paintings, the thrice reproduced images in the Sonetti resurrect what the Vatican did not want in the hands of good Christians — the exposure of the perversion and courtesans occurring behind the Vatican walls. Perhaps explored to a fuller extent in the literature of Aretino among other erotic authors, sexually explicit content in the time of the Modi was considered perverse and exceptionally sinful. In 1563, the final sessions would be held, the Book of Daniel would be considered canonical by the Church, and the treatment of images would be of utmost concern regarding textual and iconographic accuracy. In the undercurrent of the sessions, Alessandro Allori’s Susanna and the Elders, and the Susanna imagery in general, marks perhaps the most important intersection between narrative scenes and a newfound, obscene narrative in sixteenth century Italian painting. While Guercino and Domenichino created unique renditions of the text some decades later, Allori’s 1561 Susanna and the Elders surpasses most painted attempts at this scene because of its exceptionally graphic nature. Allori’s elders are not necessarily aware of their external viewers, instead, they are beholden to Susanna’s pictorial, hallucinatory, imagined consent.

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke. “The Elders and Susanna.” Biblical Interpretation; A Journal of Contemporary Approaches 1, no. 1 (1993): 1-19.

Freedberg, David. The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Frantz, David O. Festum Voluptatis: A Study of Renaissance Erotica. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989.

Kren, Thomas, Stephen J. Campbell and Jill Burke. The Renaissance Nude. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018.

Lawner, Lynne. I Modi: The Sixteen Pleasures: An Erotic Album of the Italian Renaissance: Giulio Romano, Marcantonio Raimondi, Pietro Aretino, and Count Jean-Frederic-Maximilien de Waldeck. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1988.

Nagel, Alexander. The Controversy of Renaissance Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality. London: Routledge, 1992.

Olszewski, Edward J. “Expanding the Litany for Susanna and the Elders.” Notes in the History of Art 26, no. 3 (2007): 42-48.

Spolsky, Ellen. The Judgment of Susanna: Authority and Witness. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1996.

Spolsky, Ellen. Satisfying Skepticism: Embodied Knowledge in the Early Modern World. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001.

Talvacchia, Bette. Taking Positions: On the Erotic in Renaissance Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Footnotes

[1] Lawner, 9, 17.

[2] Nagel, 223.

[3] See (Olszewski, 44, 46). The Old Testament story appears either as Chapter 13 in the Book of Daniel, or within the Apocrypha. Though the history of the Book of Susanna is complex, we may assume that the painters were working off of the Hellenized Theodotion version of the story found in the Jewish text: the Old Greek Septuagint (Spolsky, Satisfying Skepticism, 111). By Theodotion’s own time in Alexandria in the second century B.C.E, the pastoral was a popular approach to Greek romances (117-118).

[4] Talvacchia, 103.

[5] Kren, 19

[6] Kren, 25

[7] Kren, 27. See also (Freedberg, 346) for a discussion on the removal of the painting.

[8] Talvacchia, 101.

[9] Talvacchia, 102, 104-05.

[10] Talvacchia, 111.

[11] Talvacchia, 112.

[12] Nagel, 223.

[13] Nagel, 230.

[14] Nagel, 223. See also (Lawner, 3) for the measures of restricting circulation of the Modi which were so severe that reprinting of the series was deemed “punishable by death”.

[15] Nagel, 231. The history of positions that were acceptable and unacceptable is rather complex. Augustine argued for the overall blamelessness of sex for the purposes of procreation (231). More critical interpretations derive from Thomas Aquinas who categorized the “natural” and “unnatural” positions such as orifices not used for procreation (231).

[16] Lawner, 30.

[17] Lawner, 22-26.

[18] Giulio Romano’s all’antica imagery, and the deliberate numbering of 16 positions, carefully references equally ancient traditions of Parrhasias’ paintings for the emperor Tiberius on the island of Capri (Talvacchia, 57). Romano himself was a coin collector and likely owned spintriae, minted coins numbered 1-16 depicting various sexual positions to “commemorate such wicked compartment” of Tiberius. In the sixteenth century Sebastiano Erizzo’s account, based heavily on Suetonius, furnished Tiberius’s attachment to the spintriae although scholars now credit the coins to the emperor Domitian (56). Historical inaccuracies aside, Romano was acutely aware of the loaded connotations, concerning art and Roman imperial debauchery, behind his positions.

[19] Talvacchia, 11.

[20] Talvacchia, 11.

[21] Talvacchia, 12.

[22] Talvacchia, 66-67. Aretino’s name “became a password for obscene art and literature” as his work allowed him to be continentally well-known by the early seventeenth century.

[23] Lawner, 6.

[24] Lawner, 41. Posture 11 is the only woodcut out of the set that explicitly depicts another individual viewing the couple. The only other example of a third party is Posture 14 which includes another individual; directly referred to as “Cupid” by the male figure. In this scene, Cupid pulls a cart that the couple lays on in the middle of an enclosed room with one window revealing a simple nature scene of terrain and thin clouds, the male figure shouts “You little prick! Don’t keep pulling the cart / Cupid, you bastard, stop it!” (86)

[25] Lawner, 80.

[26] Lawner, 30. Lawner argues that the Modi “represents a combination, and amplification of these various genres: the literary catalogs and tariffs, the lists of lovemaking positions, the albums and the galleries of courtesan portraiture”.

[27] Lawner, 8-9. See also (Frantz, 50) for an alternate translation by Thomas C. Chubb from 1967. In comparison with Lawner’s version, Chubb softens sentiments expressed by Aretino, especially in the final sentence of my epigraph; “What wrong is there in beholding a man possess a woman?”(50). See also (Talvacchia 85-86) for a third translation of Aretino’s letter to Zatti.

[28] Lawner, 9. Aretino explicitly refers to “that thing nature gave us for the preservation of the species” (emphasis mine) and proceeds to fire off names such as Pietro Bembo, Titian, and Michelangelo, along with “Popes, emperors, and kings”(9). Talvacchia uses these names to support the letter’s later date of 1537 “since various artists and writers named […] became friends of Aretino in the 1530s” (233).

[29] Lawner, 9. See also (Frantz, 50) for the Chubb translation of this excerpt which reads more elegantly than my preferred choice herein. Lawner’s translation emphasizes the jagged rhythms of the actions of hands. Whereas Chubb waxes that hands “gamble away money, sign false testimony, make lewd gestures, snatch, tug, rain down fisticuffs, wound and slay” (50).

[30] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 102

[31] Lawner, 9.

[32] Freedberg, 324.

[33] Freedberg, 324.

[34] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 102-103.

[35] Nead, 25.

[36] Bal, 13.

[37] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 106.

[38] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 110.

[39] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 53.

[40] Spolsky, Satisfying Skepticism, 127.

[41] Spolsky, Satisfying Skepticism, 127.

[42] Bal, 5.

[43] Bal, 8.

[44] Freedberg, 355.

[45] Nagel, 236. Nagel’s discussion of the Modi in the context of serious religious art underpins the acknowledgment that the images “were inseparable from serious art” because “they emanated from the authoritative center. They had papal Rome written all over them” (236).

[46] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 113-114. There is a clear connection between Daniel and the “god in the machine” motif which would explain how the Theodotion version may have been a direct reference for early modern painters tasked with visualizing the garden scene.

[47] Spolsky, Judgment of Susanna, 106.

About the Author

Daniel Heberle graduated from the University of Rochester in May 2024 with a B.A. in Art History and a minor in Spanish. The present article was from a Spring 2023 independent study. More recent research has included work on Goya’s Black Paintings, Spanish encounters with Mexica featherwork, and workshop/legal practice related to the El Greco in the Memorial Art Gallery. With a focus on the early modern Hispanic world, Daniel is continuing his research in the Rhetorics of Art, Space and Culture: Ph.D. program in Art History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

Cite this Article

Heberle, D., Heuer, C. (2024). Voyeur & Violator: The Obscene Narrative in Early Modern Italy. University of Rochester, Journal of Undergraduate Research, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.47761/YYAT4860

JUR | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License![]()