History

Frederick Douglass: Man of Pictures

Spring 2024, Volume 22, Issue 2

Rose Frank ’24, Michael Jarvis*

https://doi.org/10.47761/URZR8898

Introduction

History remembers Frederick Douglass as a man of words. He is recognized for his captivating speeches advocating for abolition, his three autobiographies, whose literary qualities belie the fact that Douglass taught himself to read while still enslaved, and his newspaper, The North Star, which circulated anti-slavery content in the northeast in the years leading up to the Civil War. Despite recognizing Douglass’s masterful storytelling, we often overlook how he had extended this into the visual realm.

Douglass matured alongside the rise of photography in 1840s America, and the two intertwined throughout the 19th-century. Originating as a French invention, photography was swiftly integrated into the U.S.’s entrepreneurial culture. As photography studios began to open, Douglass traveled across the country delivering anti-slavery speeches, where he likely encountered this exciting new medium. Throughout his life, Douglass sat for numerous photographs and wrote extensively on the subject. Recognizing that photographs captured portraits more affordably compared to paintings, Douglass envisioned this technology as a democratizing tool, challenging the tradition of reserving portraits for wealthy elites. He took many photographs of himself and delivered multiple lectures, presenting his views on photography as a democratizing force capable of dismantling class and racial barriers within the U.S. Reevaluating Douglass as a photography pioneer highlights his profound understanding of the medium’s potential to democratize portraiture and challenge societal barriers in the 19th-century United States.

Part I: Daguerreotypes

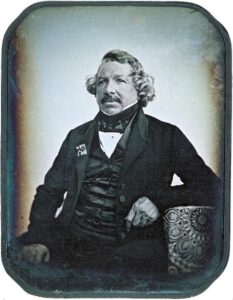

The story of Frederick Douglass and his profound connection with photography begins in 1820’s France. It was in this period that Louis Daguerre, a masterful theater set painter, dedicated himself to devising a method for permanently preserving images using sunlight. A seasoned artist, Daguerre was accustomed to using his camera obscura, which was a draftsman’s aid consisting of a wooden box with a small aperture. This contraption allowed light to filter through, projecting a reversed image onto the surface inside.[1] If Daguerre could only figure out how to preserve this image on the page, then it could open up a new realm of possibilities in the theater and art world, and would cement him in the annals of history as not only a great painter, but as a revolutionary inventor.

Daguerre took twenty years to accomplish his lofty goal. Over time, Daguerre realized he could permanently capture images on silver plated sheets of copper coated in silver iodide, a light sensitive chemical. By exposing these plates to light through a camera lens, he was able to fix the image onto the sheet using a mixture of mercury fumes and saline solution.[2] In 1839, the French Government purchased rights to the daguerreotype process and shared it with the public. In return, Daguerre received generous pensions and yearly payments throughout the rest of his life.[3]

Daguerre’s efforts culminated in a landmark moment in the history of visual representation. Were it not for the invention of the daguerreotype, photography as we know it today would not exist. Throughout the rest of the 19th-century, individuals across the world improved upon Daguerre’s foundations. They refined this technology to better suit the demands of the modern era, experimenting and adapting photography to cater to their specific needs. This dynamic process of experimentation and adaptation allowed photography to find a meaningful place within many cultures, as individuals and communities explored how to harness this exciting medium.[4]

Figure 1: Louis Daguerre posing for a daguerreotype in 1844 (International Photography Hall of Fame Museum)

The news and use of Daguerre’s invention quickly spread across the world, and the United States was particularly quick to adopt this new technology: the first daguerreotype produced in the United States was made just four weeks after the process was made public in France. Subsequently, the first photography studio opened in New York City in 1840, just a year after the initial announcement. By the end of the 1840’s, daguerreian photography studios had opened in every major city in the country, and the United States became a world leader in daguerreotype production.[5]

Figure 2: Modern example of a daguerreotype plate with image transferred (The George Eastman Museum)

The U.S. quickly adopted daguerreotypes due to its enduring culture of improvement and commitment to experimentation, a legacy dating back to the nation’s founding. European colonists had long viewed the United States as a place of opportunity, and many immigrated to this new land seeking to escape the rigid and oppressive hierarchical structures of their home nations.[6] Free from the shackles of rigid social hierarchy, American citizens believed they were uniquely positioned to achieve unprecedented heights. With inexhaustible land, energy, and, as Alexander Hamilton noted in 1791, “a peculiar aptitude for mechanic[al] improvements”, Americans saw themselves as the natural inheritors of mankind’s progressive march.[7] By the 1840s, Americans had already demonstrated an impressive repertoire of achievements including the Erie Canal and the invention of the steamboat and cotton gin.[8] Hence when daguerreotypes reached American soil, this medium was immediately absorbed by a culture that valued ambition, innovation, and improvement.

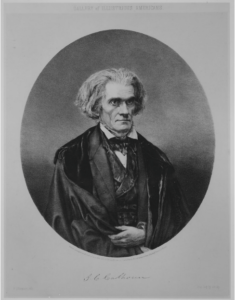

Americans sought to apply photography to portraiture[9], however early exposure times for daguerreotypes took up to an hour, making it an impractical endeavor. Experiments in Europe and the U.S. soon resulted in more light-sensitive plates which cut exposure times to only a few minutes, making portraiture feasible. Wealthy families, important figures, and common people alike sat for self-portraits in these studios, and it quickly became the most popular genre of photography in the U.S.[10] As this technology spread throughout the country, people started to develop certain norms in portraying individuals. Some artists, like Mathew B. Brady of New York City, preferred to depict their sitters in serious, severe expressions in front of a plain backdrop. This image of John C. Calhoun is representative of Brady’s preferred style: [11]

Figure 3: Print based on a daguerreotype of John C. Calhoun from “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Figure 3: Print based on a daguerreotype of John C. Calhoun from “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Unlike Brady’s formal and stern portrayals, other photographers, like Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes, took a more relaxed approach. In 1843, they established a daguerreotype studio in Boston and embraced a more informal style, presenting figures as they naturally appeared in everyday life, in contrast to capturing only the upper bodies of rigid, carefully groomed, and stern-looking subjects, as Brady did.[12]

Figure 4: A portrait of Lola Montez, famous Spanish dancer and mistress of King Louis I of Bavaria, taken in the Southworth and Hawes studio in 1850. Notice her relaxed and effortless gaze as she dangles a cigarette over an armchair (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

As the 19th-century progressed, technological advancements in each decade made photography increasingly efficient, affordable, and accessible. The mid 19th-century marked an exciting period of exploration as individuals embraced and personalized this evolving process. It was into this dynamic era that Frederick Douglass entered adulthood.

Part II: Frederick Douglass’s Early Life

Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in 1838[13], just one year before the technology for the daguerreotype was released to the public. Douglass had been living in Baltimore working for his master’s in-laws as a ship’s caulker and tradesman. At first, Hugh and Sophia Auld had welcomed Douglass into their family, teaching him how to read and showing him a kindness no white people had ever granted Douglass before. Douglass was shocked by their generosity and felt himself to be a part of their family. Soon, however, their kindness turned into bitter resentment as the couple realized that slavery worked best when slave owners dehumanized their slaves. If the Aulds were to continue treating Douglass as the child he was, and not as the slave they wanted him to be, then Douglass might become rebellious against their authority. In response, the Aulds took away his reading materials and harshly watched over his every move. Gone were the days of warmth and comfort; now Douglass was back to being treated like a slave[14].

However, Douglass no longer felt like a slave. He noticed his reading lessons began to cause a shift in his masters’ behavior. Recognizing that literacy could be a pathway to freedom, Douglass committed himself to secretly acquiring this skill– trading stolen bread from home with immigrant boys in the streets in exchange for reading lessons, and practicing writing when the Aulds were not watching[15]. Throughout the years, Douglass taught himself how to read and write–a remarkable achievement demonstrating his intelligence and determination. This early exposure to the transformative power of words stayed with Douglass throughout his life, ultimately shaping his future political persona.

When Douglass was about twenty years old, he escaped from Baltimore and headed North to establish his life as a free man. Dressed as a sailor and armed with fraudulent identification papers, he boarded trains, avoided eye contact with familiar faces, and eventually made his way to the free state of Massachusetts.[16] Despite the challenges of starting afresh, Douglass created a life for himself in New Bedford, where he worked odd jobs sawing wood, digging cellars, and moving heavy caskets of oil at an oil refinery.[17] He became an avid reader of The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper run by the stoutly religious William Lloyd Garrison, and began attending meetings held by the local abolitionist movement.[18] Although Douglass had found a routine in the city, he was not destined to lead a life of manual labor. Within a few years out of slavery, he would soon find himself embarking on another adventure.

In 1841, Douglass attended an anti-slavery convention in Nantucket that changed his life forever. Douglass had demonstrated his talent as an orator in New Bedford by delivering sermons at a local black church, but did not expect to participate in the convention. Fortunately, a prominent abolitionist had witnessed his skills in New Bedford and was so impressed that when he recognized Douglass at the anti-slavery convention, he asked Douglass to give an impromptu speech.[19] At this early point in Douglass’s young life, his appearance would have been striking to a mostly white audience. Shy in demeanor and strong in stature, Douglass had physical features that commanded attention—a strong chin, chiseled cheekbones, and well-dressed in his signature formal jacket and white button down shirt. Although Douglass could never recall exactly what he said that evening, it is evident to have been an incredible performance. A reporter for the National Anti-Slavery Standard remarked on the event, “Flinty hearts were pierced, and cold ones melted by his eloquence. Our best pleaders for the slave held their breath for fear of interrupting him.”[20] It was clear to everyone in the audience that Douglass was born for public speaking. As soon as the meeting ended, he was asked to join William Lloyd Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society as a traveling agent.[21] Over the following three years, he roamed across the northeast and midwest regions of the country with a team of orators, giving speeches in support of the abolitionist cause. This experience launched his rise to political and national fame.

Part III: Frederick Douglass the Activist

From 1841 to 1845, Douglass traveled with Garrison’s team and made use of the growing number of accessible daguerreotype studios, making it a point to have his portrait taken in nearly every town he visited.[22] The abundance of surviving images from this period depicts a progressive arc in which Douglass learned to navigate the medium, as he strategically adapted his posture to create images of himself that aligned with the message he wanted to project.

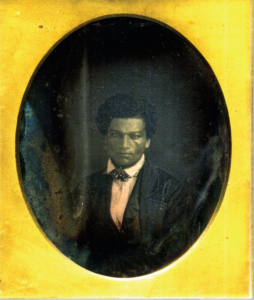

Douglass’s journey in mastering his visual representation is evident when scrutinizing his earlier portraits. The earliest known daguerreotype of Douglass, taken in 1841, captures a sense of bewilderment or, in his own words, a “statue-like” demeanor. His demeanor can be attributed in part to the extended exposure times of 1841, lasting several minutes compared to the later, shorter durations of just a few seconds. It is also likely that Douglass had not yet determined his preferred composition; this image takes an oddly zoomed out perspective, placing Douglass in the center of the photograph and leaving much empty space above his head. The result (Figure 5) gives a sense that Douglass is placed far in the back of the image, as opposed to proudly facing the viewer from the front.

Figure 5: The earliest known portrait of Douglass (Courtesy of the Collection of Greg French)

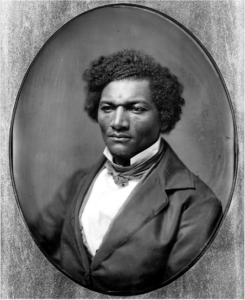

In a subsequent 1843 daguerreotype (Figure 6), the camera is positioned at chest level, and his gaze is directed slightly upwards and to one side, adhering to the recommended pose outlined in photographic manuals.[23] This particular gaze was thought to convey confidence and intelligence, but Douglass had not yet mastered the pose. In this daguerreotype, his eyes appear partially open and veiled in shadows, indicating that he was still navigating the nuances of proper posing.

Figure 6: Douglass adapted to the photographic pose. Likely taken between 1841 and 1843 by an unknown photographer (Onondaga Historical Association)

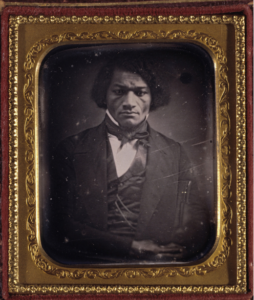

A later daguerreotype taken in 1848 by the Edward White Gallery (Figure 7) shows Douglass’ continued experimentation with the photography medium. Here, Douglass’s disposition is noticeably guarded, with a sidelong glance and head slightly lowered, suggesting a reluctance to fully trust the camera or the photographer. These three images indicate Douglass’s uncertainty in his appearance and the way he presented himself to the public, which is underscored in a letter he wrote in 1846 to another fugitive slave, admitting that, “I got real low spirits yesterday…I looked so ugly that I hated to see myself in the glass.”[24]

Figure 7: This portrait conveys Douglass’s insecurity in front of the camera (Albert Cook Myers Collection)

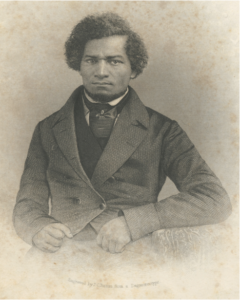

Douglass’s uncertainty in front of the camera did not last long. By 1850, Douglass adopted his distinctive look, evident in the daguerreotype below (Figure 8). He gazes sternly into the camera with a calculated pose, conveying a sense of deliberate defiance. The frontispiece of his popular second autobiography, “My Bondage and My Freedom”, published in 1855, mirrors the daguerreotype, projecting a similar air of calculated defiance (Figure 9). Modeled on another lost photograph, it highlights his physical strength and confidence, depicting a sturdy young man with furrowed brows and firm lips. This became Douglass’s signature pose in the late 1850s and throughout the Civil War.[25]

Figure 8: 1850, unknown photographer (National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

Figure 9: Engraving by John Chester Buttre based off of a lost daguerreotype. Frontispiece for “My Bondage My Freedom” (University of Rochester Rare Books Library)

In these images, we not only witness Douglass mastering the technical aspects of photography, but also his growing confidence in his own self-expression. As Douglass gained mastery of this visual medium, the images documented his journey from a determined yet uncertain political activist, to a more assured and self-confident leader.

The transformation evident in Douglass’s self-portraits mirrors his broader journey—from a former slave determined to share his story into an intellectual activist challenging the very foundations of slavery and discrimination. The visual narrative encapsulates Douglass’s evolution, illustrating the intersection of his political activism, intellectual endeavors, and mastery of the emerging art of photography.

Part IV: From Enthusiast to Theorist

After two years speaking independently in the United Kingdom, Frederick Douglass returned to the U.S. in 1847 and split from the Garrisonian crusade due to differences in their approaches to abolition and William Lloyd Garrison’s attempts to control and suppress Douglass’s intellectual abilities.[26] From the beginning of their partnership, Garrison’s troupe sought to hold back Douglass’s talents. Douglass recalled that Garrison’s associates urged him to speak with less eloquence so he sounded more like an uneducated former slave. They stated it was “better to have a little of the plantation speech than not” and cautioned against Douglass appearing “too learned”.[27] Tension persisted throughout their relationship because Douglass aimed to go beyond, whereas Garrison preferred to keep him fixed within the role of an uneducated former slave to support the arguments made by white abolitionists. Their conflict led Douglass to part ways with the Garrisonian approach, marking a significant moment in his journey toward greater independence and intellectual freedom within the abolitionist movement.

After the split, Douglass decided to settle in Rochester, New York, where he established his own newspaper, The North Star. This platform allowed him to publish views and opinions that had been restricted under Garrison’s oversight.[28] Douglass not only asserted his editorial independence but also began expressing his thoughts on photography in a more intellectual manner, moving beyond the realm of self-portraiture.

Douglass recognized the potential of photography to dismantle racial barriers within the United States. In 1854, he prominently featured an article on the accomplished black photographer James Presley Ball. Ball had opened a studio in Cincinnati that became known as the “Great Daguerreian Gallery of the West”[29] Impressed with Ball’s gallery, Douglass showcased it along with an engraving of the studio on the front page of his newspaper. For Douglass, Ball’s studio symbolized a vision of the integrated nation he aspired to see. It served as a testament to the acknowledgment of African American artists’ contributions to the nation’s visual culture and envisioned a space where individuals of different races could come together, united by their shared passion for art. In this way, Ball’s studio became a tangible representation of Douglass’s vision for a more inclusive and integrated future.[30]

Douglass extensively explored photography in his later years, delivering four lectures on the subject.[31] In these lectures, he articulated a theory for the uses of photography that was both radical and unprecedented for its time, given that photography was still a developing medium. On December 3, 1861, at the Boston Tremont Temple, Douglass gave a lecture called “Lecture on Pictures” to a group of abolitionists, fellow activists, and community members. Departing from his usual presentation style (which included frequent improvisation and interaction with the crowd), Douglass took a more scholarly approach by reading from a stack of handwritten papers.[32] In this address, Douglass articulated his views on how photography had the potential to bridge racial and economic divides in the United States. He emphasized that the affordability and accessibility of photography allowed even the poorest individuals to experience a sense of importance, noting, “the humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty, with all its precious treasures, could purchase fifty years ago.”[33]

He also lauded photography for presenting subjects as they truly appeared, immune to artificial improvements or distortions. Douglass’s thoughts were undoubtedly shaped by the challenges he had faced in representing himself to the public as he desired.[34] From the constraints imposed by Garrison on Douglass’s intellect to the manipulation of Douglass’s engravings by white artists, photography held significant importance for him because it emphasized the truth of its subjects.

When Douglass delivered his “Lecture on Pictures”, a reviewer praised him as a “genius”, stating, “no one has crystalized [the theory behind photography] more clearly than Mr. Douglass; and this seemed to be the feeling of the highly educated and thinking audience.”[35] By 1861, Douglass had evolved from an uncertain young man posing before a camera to a confident master of the craft, assigning philosophical meaning to creations from this transformative technology.

Part V: Rethinking Frederick Douglass

Douglass’s engagement with photography occurred during a Goldilocks period in the history of the medium. As technological advancements after Douglass’s era led to reduced shutter speeds, cameras became worse at capturing images of black individuals. Shorter shutter speeds made it more difficult to capture depth and detail in darker skin tones, and as W.E.B. Du Bois noted, few white photographers bothered to remedy this.[36] Since Douglass’s many portraits were captured by daguerreotypes with longer shutter speeds, they yielded higher quality images than those captured in the later nineteenth century. Douglass’s contributions to photography, therefore, occurred at the perfect moment in the medium’s development to leave behind a collection of photographs that continue to stun viewers today.

Historians often emphasize that Douglass was the most photographed American in the nineteenth century to underscore the fame he achieved in his own time. While this is true, it oversimplifies his much more complex and intentional relationship with photography. It leaves out an entire portion of Douglass’s intellectual life, his fascination with photography and its potential to generate social change. Beyond his success as an abolitionist who happened to sit for numerous portraits, Douglass warrants recognition as a pioneering photography theorist. His intellectual engagement with photography extended far beyond the lens, reflecting a profound understanding of its potential to drive social change.

Bibliography

David Blight. “Prophet of Freedom” New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Britannica. “Photography: Photography’s early evolution (c. 1840–c. 1900).” https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography/Photographys-early-evolution-c-1840-c-1900.

Douglass, Frederick. “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.” Dover Thrift Editions. Lexington: Dover Publications, 1995.

Douglass, Frederick. “Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.” Boston: De Wolfe & Fiske Co., 1892.

Daniel Feller. “The Jacksonian Promise” Baltimore: The University of Johns Hopkins Press, 1995.

Eastman Museum. “Daguerreotype Research.” Accessed December 13, 2023. https://www.eastman.org/daguerreotype-research.

Gates, Henry Louis. “Frederick Douglass’s Camera Obscura.” Aperture, no. 223 (2016): 25–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43825318.

Hirshman, Linda. “The Speech That Launched Frederick Douglass’s Life as an Abolitionist.” https://time.com/6148114/frederick-douglasss-abolitionist-book/.

International Photography Hall of Fame. “Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre.” https://iphf.org/inductees/louis-jacques-mande-daguerre/.

MIT Press. “The Early American Daguerreotype.” https://mitpress.mit.edu/the-early-american-daguerreotype/.

Snelling, Henry H. “The History and Practice of the Art of Photography; or, the Production of Pictures Through the Agency of Light.” New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849.

Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier. “Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American.” New York: Liveright Publishing, 2015.

Willis, Deborah. “The Sociologist’s Eye: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Paris Exposition.” In A Small Nation of People: W. E. B. Du Bois and African American Portraits of Progress, by David Levering Lewis and Deborah Willis, 51. New York, 2003.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Daguerreotype of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre.” Accessed December 13, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/268341.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Gallery of Illustrious Americans.” Accessed December 13, 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/339862.

Footnotes

[1] Vi Whitmire, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, International Photography Hall of Fame, https://iphf.org/inductees/louis-jacques-mande-daguerre/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Britannica, Photography: Photography’s Early Evolution, https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography/Photographys-early-evolution-c-1840-c-1900.

[4] Britannica, Photography’s Early Evolution

[5] Ibid.

[6] Daniel Feller, The Jacksonian Promise, (Baltimore: The University of Johns Hopkins Press, 1995), 7.

[7] Feller, The Jacksonian Promise, 26-28.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Britannica, Photography’s Early Evolution.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Blight, Prophet of Freedom, 146.

[14] Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Chapters 5-6.

[15] Douglass, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Chapter 7.

[16] David Blight, Prophet of Freedom (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018), 110-112.

[17] Frederick Douglass, Life and the Times of Frederick Douglass, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/dougl92/dougl92.html, 259.

[18] Douglass, Life and the Times, 263-265.

[19] Douglass, Life and the Times, 266-267.

[20] Linda Hirshman, The Speech That Launched Frederick Douglass’s Life as an Abolitionist https://time.com/6148114/frederick-douglasss-abolitionist-book/.

[21] Douglass, Life and the Times, 271.

[22] Stauffer, John, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2015).

[23] Snelling, Henry H, The History and Practice of the Art of Photography; or, the Production of Pictures Through the Agency of Light (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1849).

[24] Douglass to Ruth Cox, May 16, 1846

[25] Stauffer, Picturing Frederick Douglass, 50-54.

[26] Frederick Douglass, Life and the Times of Frederick Douglass, 268-269.

[27] Page 269 of Life and the Times. Douglass did not reproach these men for their comments as he understood that they “were actuated by the best of motives.” Nevertheless, he emphasized his strong desire for the freedom to express his thoughts openly.

[28] Frederick Douglass, Life and the Times of Frederick Douglass, 317-322.

[29] Stauffer, Picturing Frederick Douglass, 36.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Stauffer, Picturing Frederick Douglass, 10.

[32] Stauffer, 338-339.

[33] Stauffer, 340.

[34] Stauffer, 27.

[35] Stauffer, 338.

[36] Deborah Willis, The Sociologist’s Eye: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Paris Exposition, (New York, 2003), 51.

About the Author

While taking Professor Jarvis’s Frederick Douglass’s Rochester course I became very interested in Douglass’s relationship to photography. Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century with over 160 surviving photos and portraits. While examining original photographs of Douglass housed in the Rare Books and Special Collections Library, I grew increasingly curious about what motivated Douglass to sit for so many portraits. It was fascinating to uncover Douglass’s strategic approach to photography and to realize how he utilized this medium to advance the abolitionist movement. I am grateful to Professor Jarvis and the Rare Books team for providing the support and resources essential for conducting this research project.

Cite this Article

Frank, R., Jarvis, M. (2024). Frederick Douglass: Man of Pictures. University of Rochester, Journal of Undergraduate Research, 22(2). https://doi.org/10.47761/URZR8898

JUR | Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License![]()