Although slavery was abolished 150 years ago, its political legacy is alive and well, according to researchers who performed a new county-by-county analysis of census data and opinion polls of more than 39,000 southern whites.

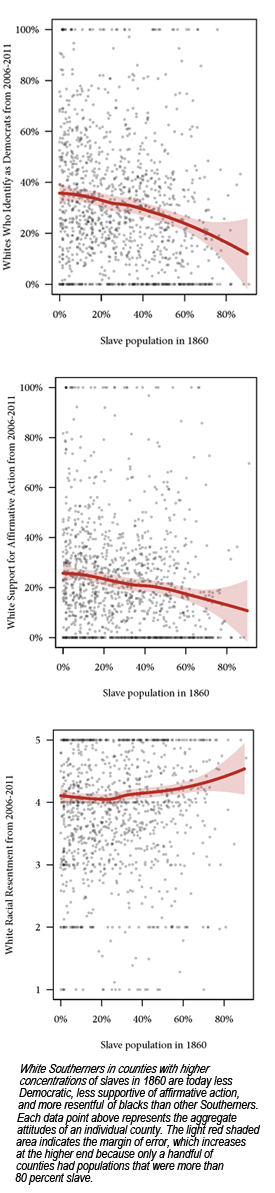

The team of political scientists found that white Southerners who live today in the Cotton Belt where slavery and the plantation economy dominated are much more likely to express more negative attitudes toward blacks than their fellow Southerners who live in nearby areas that had few slaves. Residents of these former slavery strongholds are also more likely to identify as Republican and to express opposition to race-related policies such as affirmative action.

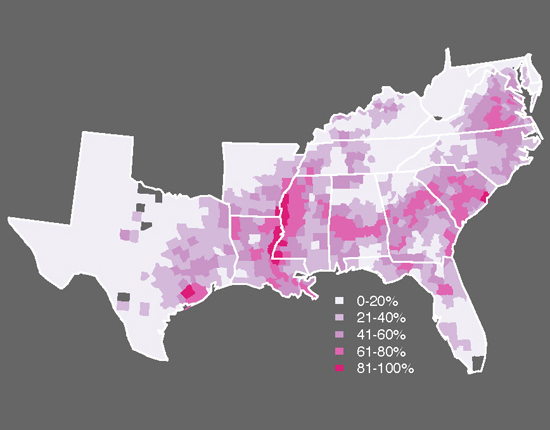

Slaves were concentrated in counties where cotton thrived, as shown in the above map based on the 1860 census. White Southerners in these same areas today express more racial resentment and are more likely to be Republican and oppose affirmative action, than other Southerners.

Conducted by Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen from the University of Rochester, the research is believed to be the first to demonstrate quantitatively the lasting effects of slavery on contemporary political attitudes in the American South. The findings hold even when other dynamics often associated with racial animosity are factored in, such as present day concentrations of African Americans in an area, or whether an area is urban or rural.

"Slavery does not explain all forms of current day racism," says Acharya. "But the data clearly demonstrates that the legacy of the plantation economy and its reliance on the forced labor of African Americans continues to exacerbate racial bias in the Deep South."

The findings are reported in a working paper that will be presented for the first time at the Politics of Race, Immigration, and Ethnicity Consortium at the University of California at Riverside on Sept. 27.

The study looked at data from 93 percent of the 1,344 Southern counties in the Cotton Belt—the crescent-shaped band where plantations flourished from the late 18th century into the 20th century. The researchers found that a 20 percent increase in the percentage of slaves in a county's pre-Civil War population is associated with a 3 percent decrease in whites who identify as Democrats today and a 2.4 percent decrease in the number of whites who support affirmative action.

The "slavery effect" accounts for an up to 15 percentage point difference in party affiliation today; about 30 percent of whites in former slave plantation regions report being Democrats, compared to 40 to 45 percent white Democrats in counties that had less than 3 percent slaves, according to the authors. Despite the region's similarity in culture and its shared history of legalized slavery and Jim Crow laws, "the South is not monolithic," says Blackwell.

Their analysis shows that without slavery, the South today might look fairly similar politically to the North. The authors compared counties in the South in which slaves were rare—less than 3 percent of the population—with counties in the North that were matched by geography, farm value per capita, and total county population. The result? There is little difference in political views today among residents in the two regions.

"In political circles, the South's political conservatism is often credited to 'Southern exceptionalism,'" says Blackwell. "But the data shows that such modern-day political differences primarily rise from the historical presence of many slaves."

But how is it possible that an institution so long outlawed continues to influence views in the 21st century? The authors point to both economic and cultural explanations. Although slavery was banned, the economic incentives to exploit former slaves persisted well into the 20th century. "Before mechanization, cotton was not really economically viable without massive amounts of cheap labor," explains Sen. After the Civil War, southern landowners resorted to racial violence and Jim Crow laws to coerce black field hands, depress wages, and tie tenant farmer to plantations.

"Whereas slavery only required a majority of (powerful) whites in the state to support it, widespread repression and political violence required the support and involvement of entire communities," the authors write.

Again comparing the county-by-county data, the researchers found evidence of the relationship between racial violence and economics in the historical record of lynchings. Between 1882 and 1930, lynching rates were not uniform across the South, but instead were highest where cotton was king; a 10 percent increase in a county's slave population in 1860 was associated with a rise of 1.86 lynchings per 100,000 blacks. "For the average Southern county, this would represent a 20 percent increase in the rate of lynchings during this time period," says Blackwell.

By the time economic incentives to coerce black labor subsided with the introduction of machinery to harvest cotton in the 1930s, anti-black sentiment was culturally entrenched among local whites, the authors write. Those views have simply been passed down, argue the authors, citing extensive research showing that children often inherit the political attitudes of their parents and peers.

The data, says Sen, points to the importance of institutional and historical legacy when understanding political views. Most quantitative studies of voters rely on contemporary influences, such as education, income, or the degree of urbanity. The findings are also in line with research on the lingering economic effects of slavery. Studies have shown that former slave populations in Africa, South and Central America, and the United States continue to experience disparity in income, school enrollment, and vaccinations.

For the study, the authors drew on publically available data, including the 1860 census and the Cooperative Congressional Election Study, a large representative survey of American adults. No external funding was required for the analysis.