Score one for the songwriters.

John Covach, director of the Institute for Popular Music, was excited to hear that Bob Dylan, the poet laureate of the rock era, had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature on Thursday.

“Dylan was an important figure in songwriting, especially in the 1960s,” Covach says. “He was criticized by some in the folk movement for transforming the ‘we’ to ‘me’-writing songs that dealt with his own thoughts and feelings and less with ideas of social justice and change. But it’s just that turn toward the poetic that made it possible for him to even be considered for this distinguished prize in literature.”

Covach says Dylan is “deserving” of the honor bestowed by the Swedish Academy, the first for a musician and the first by an American in 23 years.

“This honor is a huge win for those of us who take popular music seriously,” he says.

6 stops on Bob Dylan’s rise to the top

by John Covach

Professor of music and director of the University’s Institute for Popular Music

Originally published: May 20, 2016

For the past five decades, Bob Dylan has influenced both music and popular culture as the unofficial spokesman for his generation (though Dylan himself resists this description). As people from around the world start to celebrate the singer’s 75th birthday, rock historian John Covach, director of Rochester’s Institute for Popular Music, identifies six stops on the singer, songwriter, and artist’s turbulent rise to the top in the 1960s.

1) Dylan’s first album was a commercial flop.

Discovered by legendary producer John Hammond, Dylan recorded his debut album for Columbia Records in 1962. Consisting mostly of covers and arrangements of traditional tunes, Bob Dylan sold so poorly that it was nicknamed “Hammond’s folly.” Columbia’s Mitch Miller had reservations about Dylan’s voice, but the Eastman School of Music graduate and host of the popular Sing Along with Mitch TV show remembered that Dylan’s album was not a financial disaster because it didn’t cost much to record a folksinger. Dylan says he realized right away that he had recorded the wrong songs: he should have performed his own music.

2) Dylan’s first commercial success came as a songwriter.

One person who recognized Dylan’s songwriting gift immediately was Artie Mogull, who signed Dylan to a publishing deal with Warner Brothers. Mogull worked to place Dylan’s songs with other artists. Peter, Paul, and Mary, for instance, had hit singles with both “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” in 1963. Dylan didn’t have an American hit as performer until “Like a Rolling Stone,” released in the summer of 1965.

3) His early songs focused on human rights and social injustice

In terms of songwriting, Dylan was initially influenced by his idol, Woody Guthrie, who often reworked traditional music with new lyrics while also chronicling social injustice. Early topical songs from Dylan are “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which addressed civil rights, and “Masters of War,” which challenged the Vietnam conflict. His later songs became increasingly focused on his own feelings and attempts to understand the world—a shift that some traditionalists in the folk movement thought of as replacing “we” with “me.” Dylan’s turn toward more personal songs, however, proved fundamental in establishing the singer-songwriter approach that has flourished ever since. In spite of the social commentary in some of his songs, Dylan has argued that he was never a “political” songwriter.

4) Dylan upset some of his earliest supporters in the folk community when he started using electric instruments.

Dylan first appeared at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, at a time when he was emerging as the darling of the folk revival. But many folk traditionalists—most famously Peter Seeger—felt betrayed by Dylan’s use of electric instruments when he appeared at the Newport Folk Festival in the summer of 1965. While accounts of exactly what happened during Dylan’s rebellious Newport performance of that year diverge, it’s clear that some fans and fellow musicians vigorously rejected Dylan’s new turn. Dylan’s response was to excoriate such false friends in his next single, “Positively Fourth Street.” That the song became a top 10 pop hit probably made its sting even more intense. As much as any event in his career, the Newport dispute made it clear that Dylan wasn’t interesting in being anybody’s darling.

5) As a performer, Dylan initially enjoyed more success in the UK than in the US.

In the wake of his disappointing debut album, Dylan signed with manager Albert Grossman, who was also managing Peter, Paul, and Mary at the time. Grossman booked Dylan to appear in a BBC television play entitled Madhouse on Castle Street, first aired in January 1963. While The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan only went to number 16 in England at the end of that year, by early 1965 his “The Times They Are A-Changin’” was a number 9 hit in the UK, riding the momentum created by a string of UK top-10 albums in 1964. Dylan’s success as a traditional folksinger in England helps explain why he met with such resistance from audiences during his 1966 tour of the UK. The electric guitars, keyboards, and drums were too much for those who had come to love the solo performer, and some booed while others walked out.

6) Dylan may have introduced the Beatles to marijuana.

In the fall of 1964—well before Dylan was a famous pop performer in his own right—Dylan met with the Beatles in their New York hotel. The Beatles had been fans of Dylan’s songwriting since at least January of that year, and Dylan is reported to have urged the lads to try getting a little more ambitious with their lyrics. The songs on the band’s next album, Help!, suggest that they took his advice. He also seems to have introduced the Fab Four to pot; Paul McCartney says he had a cannabis-drenched vision that evening and quickly wrote it down. The next day he read what he had written: “There are seven levels.”

From What’s That Sound? An Introduction to Rock and Its History (Third Edition), by John Covach and Andrew Flory. W.W. Norton & Company, 2012.

Dylan Plugs In.

In December 1960, a young folksinger arrived in New York from Minnesota, where he had been playing gigs in folk clubs and coffeehouses. Within a few months, Bob Dylan was performing in Greenwich Village and becoming increasingly active in the city’s burgeoning folk scene. By the beginning of 1964, he was among the most respected young folksingers in the United States. Dylan was not particularly well known outside the folk community, since the general pop audience associated “folk” with the music of the Kingston Trio or Peter, Paul, and Mary. Some pop listeners might have known that Dylan wrote “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” (both hits in 1963 for Peter, Paul, and Mary), but most would not have heard Dylan’s own versions, which appear on his second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963). Like many folk artists, he enjoyed success mostly on the album charts and only had the occasional hit single. Dylan’s popularity, fueled by appearances in folk clubs and on college campus was greater in the UK than in the United States. By 1964 his albums The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) and Another Side of Bob Dylan (1964) did well enough on both sides of the Atlantic to make him one of the most emulated folksingers of this period.

Dylan was a skilled performer and an even more accomplished songwriter. It was common for folksingers to write their own music, often creating new songs from tunes drawn or adapted from traditional folk melodics. Dylan’s idol Woody Guthrie frequently reworked familiar music with new lyrics that chronicled social injustice. Dylan initially followed this model, creating topical songs such as “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which addressed civil rights, and “Masters of War,” which challenged the Vietnam conflict. Dylan’s songs, however, became increasingly focused on his own feelings and attempts to understand the world. Early songs such as “Girl from the North Country” and “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” display his exceptional gifts as a songwriter. The personal lyrics of these songs arc crafted with the painstaking aesthetic attitude more common among poets than musicians.

After an enormously successful tour of the UK in 1965 (documented in the D.A. Pennebaker film Don’t Look Back), Dylan made a break with the folk tradition that would have tremendous consequences for popular music. Contrary to the folk revival orthodoxy, he had long been interested in using electric instruments in his music and a few sessions for his second album had been recorded with what was essentially a rock band; he even tried out a version of “That’s All Right (Mama).” Dylan was not satisfied with the results of these sessions and only one of the resulting tracks was used on the album (“Corrina, Corrina”). (Another of these songs, “Mixed Up Confusion,” became his first single, but it did not chart when released in 1962.) Dylan’s interest in rock instrumentation was also evident on his album Bringin’ It All Back Home (1965}, half of which used electric instruments, including his first hit single, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965). The folk community did not express an overwhelmingly negative reaction to Dylan’s electrified music when the album was released perhaps because of the strong acoustic-based material. However, when he played the Newport Folk Festival in July 1965 an enormous controversy began. As a headliner, Dylan was one of the most sought after artists at the festival. The festival program only allotted Dylan a short set, and he performed three electric numbers (“Maggie’s Farm,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “Phantom Engineer”) backed by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. When he left the stage after only a few songs, the crowd heckled Master of Ceremonies Peter Yarrow (of Peter, Paul, and Mary) until Dylan came back out. As an encore, Dylan performed acoustic versions of “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue.” Despite the positive reaction to his acoustic material, Dylan’s electric numbers met with resistance among the more traditionally minded folkies in attendance. Many senior members of the folk establishment who had strongly supported Dylan up to this point (including Pete Seeger) felt betrayed by his turn to electric instruments. Dylan’s insistence upon performing nontopical material with a rock band, made him the target of very strong criticism within folk circles.

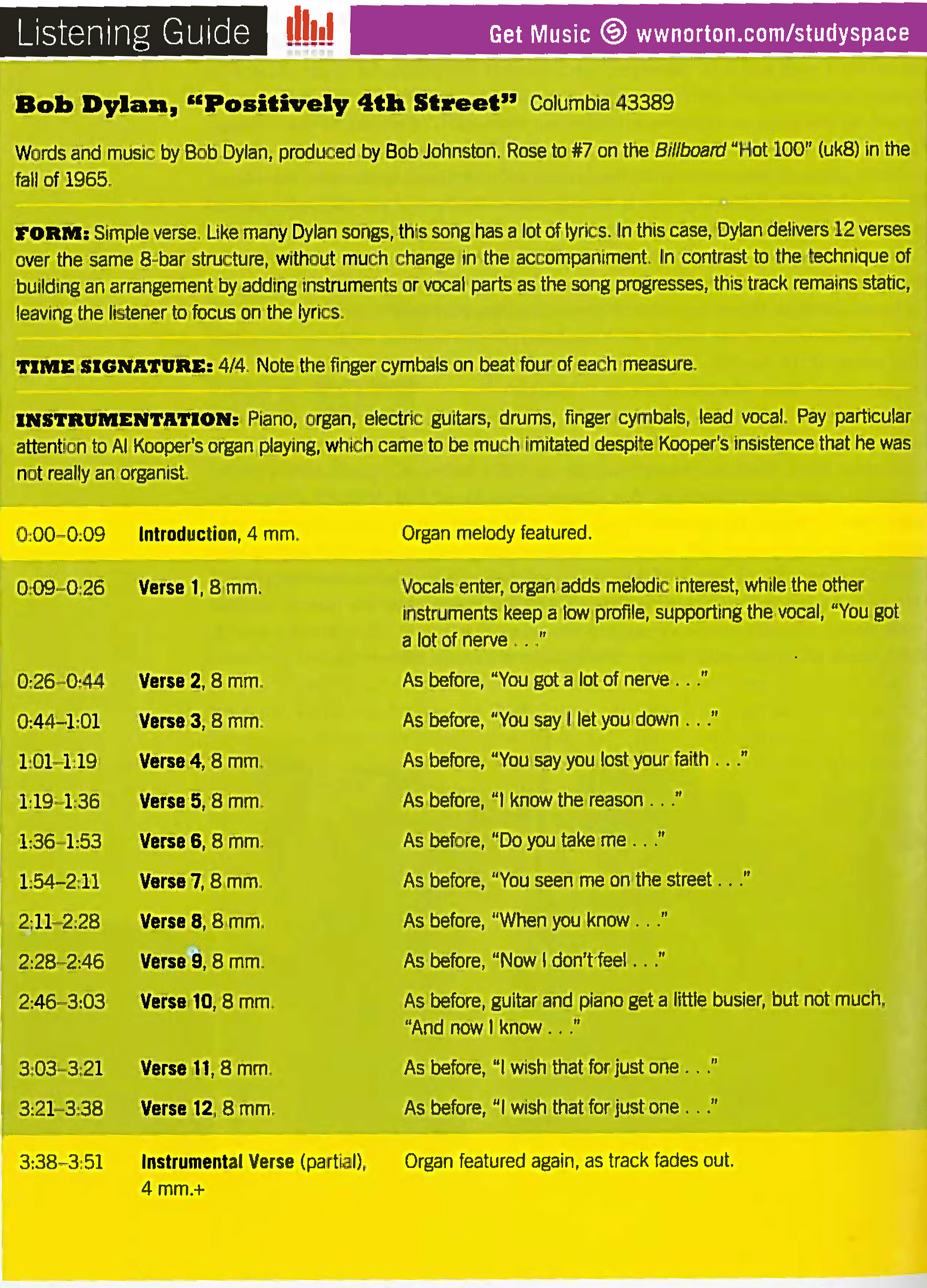

A week before the 1965 festival, Columbia Records released Dylan’s single “Like a Rolling Stone,” one of the three electric songs he performed at Newport. It was his most popular song as a performer, and rose to number two in the United States in the summer and fall of 1965. He followed with the album Highway 61 Revisited (1965) and the angry hit single, “Positively 4th Street” (1965). The folk music establishment continued to react negatively to Dylan’s use of electric instruments, and he felt betrayed by their response. As a traditional folksinger, he had written songs like “Masters of War,” which attacked those who exploited others to gain unfair social or economic advantage. Dylan referred to such tunes as “finger pointing” songs, and after his 1965 Newport performance he used “Positively 4th Street” to point his finger at the folk establishment he felt had unfairly criticized him. The fervor of Dylan’s obsession on this issue can be seen in the song’s structure, which is a simple verse form employing twelve verses. After a short four-measure introduction, Dylan plows away at verse after verse, all based on the same eight-measure harmonic pattern. The song concludes with part of a thirteenth time through the chord progression, with vocals absent and the focus on Al Kooper’s organ part, until the song fades out.