May Bragdon didn’t have access to Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, but the diaries she wrote from 1893 to 1914 include many of the same compelling visual elements — photos of May and her friends, for example, riding their bicycles in high puff sleeves, skirts and hats.

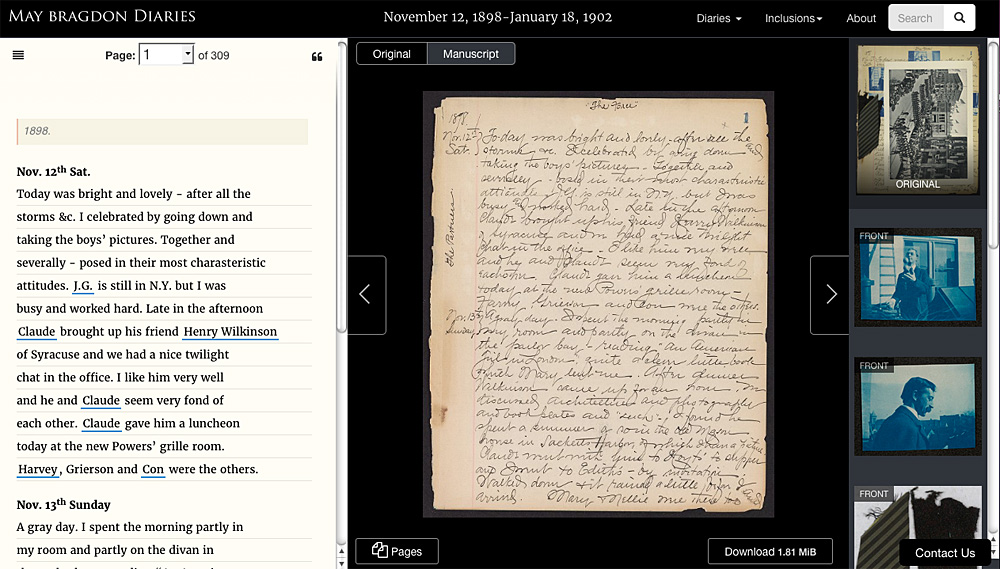

May, the sister of famed architect Claude Bragdon, pasted photographs, newspaper clippings, theater programs, correspondence, and other “inclusions” on top of her diary entries. As many as 14 items per page, and some 3,200 across the 10 volumes. Researchers literally had to lift the layers of overlapping material in order to read the writing underneath.

The diaries are a richly revealing chronology of an “ordinary” woman’s life at a time of major social change — especially for women. “May was not politically active,” says Andrea Reithmayr, a rare books and special collections librarian and curator of the Bragdon Family Papers. “However, through, for example, her descriptions of bicycle riding — in itself a liberating activity for women — or her accounts of gender inequality in the office, you can see the impact that Susan B. Anthony and others were having on so-called ordinary women.”

In order to safely provide increased access to the fragile documents, it was important to put them online. However, translating the diaries’ scrapbook-like construction to a flat screen posed immense challenges for the team of University Libraries staff, led by Reithmayr, who have published a transcribed and annotated digital edition of the 10 volumes as a resource for women’s history, most broadly, and for Rochester history in particular.

We had to do a lot of custom development in order to retain the physical context of the diaries while also taking advantage of the digital environment.” says Adam Traub, director of the Information Discovery Team, which is charged with developing tools and interfaces to expose the River Campus Library’s resources to the University community and the outside world.

Even before the website was developed, all 3,100 pages of the diaries first had to be imaged with the inclusions still attached. The effort documented how the pages looked originally. Then, each of 3,200 inclusions was removed by a conservator and the unobstructed pages of writing and all the attendant items were imaged separately.

After transcription by a vendor, a graduate student tagged people, places, dates, and things using standards of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI), a consortium which collectively develops and maintains a standard for the representation of texts in digital form. More than 500 entities central to May’s life were researched to provide background information to orient readers wherever they might join the narrative. This presented a whole new set of challenges: May had many friends who shared the same first name and who appear repeatedly in the diary without last names. Disambiguating one Edith, Charlotte, Mary, or Henry from another could only be done by a human being.

“Thank goodness there is only one Claude in May’s circle!” Reithmayr joked.

The project, which began with an anonymous donation in 2011, has taken five years to reach fruition, during which team members have spent hundreds of hours immersed in what Reithmayr affectionately refers to as “May land.”

“It was not possible for me or other members of the team to do all of the research that is possible with these diaries,” she says. Nor did they want to. “What we wanted in the end was to be able to say ‘Look at this amazing resource!’ We really hope that our faculty and students will be able to use these diaries in their teaching and learning, to apply some of the research projects that we can imagine and many that we can’t.”

The diaries offer many topics to explore.

May Bragdon was a single woman of modest means, executive secretary to Rochester architect and mail chute inventor J. G. Cutler, and later the office manager for her brother Claude’s architectural practice. She was also a bicycle “fiend.” And so were many of her friends.

May writes about “flying freely down a hill” on the bicycle she named Diana. She describes waking up at 6 a.m. and cycling eight miles before work — not something we usually associate with women of the 1890s. And she makes a special note of it whenever she decides – heaven forbid — to ride without a hat on.

“She’s in this transitional period where it’s new and somewhat daring for a woman to be out riding alone, or in the company of men to whom she is not related by blood or marriage,” says Reithmayr. “In the diaries, you can see how May and her friends are constantly negotiating change – pushing their personal envelopes toward new experiences.”

Reithmayr sees many opportunities for class projects in the diaries. For example, May often describes the exact routes she followed in and around Rochester on her bicycle and on streetcars, trains, and ferries. Using GIS, Reithmayr says, students could use period and modern maps to plot those routes, thereby visualizing and analyzing the change and growth of Rochester and its suburbs and its system of public transportation. For example, by 1900, Monroe County had one of the nation’s best systems of bike paths: where does it stand today?

May was not politically active, and not one to make sweeping social and cultural observations in her diaries. Nonetheless, many of the personal anecdotes she shares reflect social and cultural themes that will be of interest to academic researchers and average readers alike.

For example:

Visual and Cultural Studies. “May records the books she and her friends read, the plays they attended several times a week, the word games they played, and the costume parties they had” Reithmayr said. The diaries are “peppered” with theater programs that, in and of themselves, are a valuable resource. The thousands of photographs provide ample evidence of the impact of “the Kodak” — the personal camera that revolutionized how people looked at and documented the world and themselves.

“The New Woman.” In addition to cycling unescorted, May and her female friends often traveled alone and vacationed in the Adirondacks, Maine, or Georgian Bay, “climbing up mountains, rowing across stormy bays,” Reithmayr says. “We don’t usually think about women at this time camping in their 20 pounds of clothing, but there they are, and not complaining about it.” Together with details of daily domestic, work, and recreational life, and stories of marriage and childbirth, these documents are “living history.”

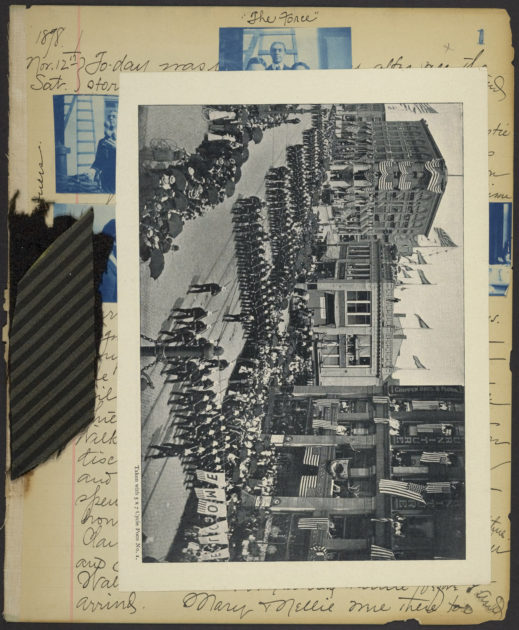

Rochester history. “Pretty much every political and social event that occurred in the city from 1893 to 1914 is in the diaries,” Reithmayr says. For example, May offers accounts of the 1901 Rochester Orphan Asylum fire, the 1904 Sibley fire, floods, elections, and even cat shows. She also includes references to the Chicago World’s Fair and the Pan-American Exposition.

To read the diaries, go to https://maybragdon.lib.rochester.edu/ Readers are strongly encouraged to share their feedback. What avenues of research are you pursuing with the diaries? Can’t find what you’re looking for? Contact andrear@library.rochester.edu or just click “contact us” at the bottom of each page.