It was a contentious campaign, with charges of sexual misconduct, corruption, and greed.

One candidate was labeled a criminal, the other a coward.

Personal attacks came on a daily basis.

Yes, the presidential election of 1800 was nasty, to use a word from this year’s campaign. In the end, Thomas Jefferson defeated incumbent John Adams, and the two didn’t speak for years.

Sound familiar? It should, says Mitchell Lovett, associate professor of marketing at the Simon Business School.

“Negative campaigning has been around as long as campaigning,” Lovett says. “It stays around because it works.”

Lovett has taught courses on social media and advertising in politics, and is an expert on negative political advertising. He’s found that the closest elections are usually the most negative, and that talking about the bad traits of a candidate becomes more effective the more you know about the candidate.

People also tend to remember negative traits more than positive ones.

“When you tell voters two positive traits about a candidate, they tend to average those out,” Lovett says. “But if you give them two negative traits, people add them together, and it makes a more lasting impression.”

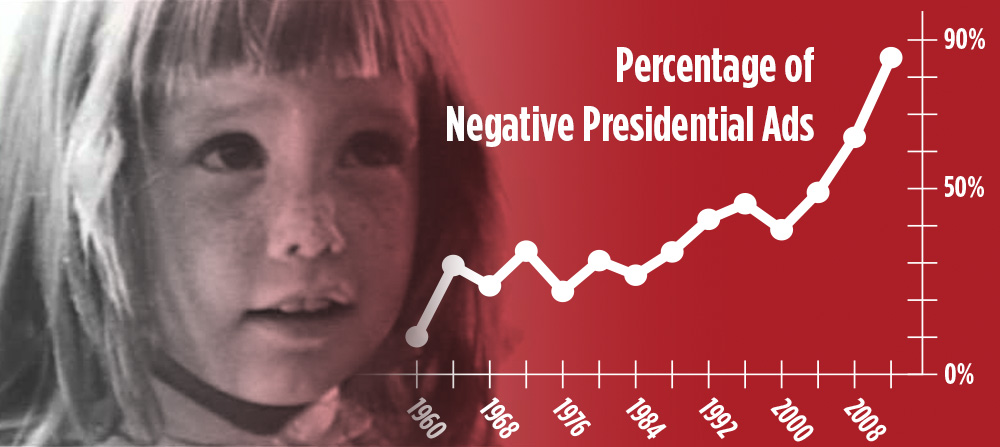

Recent elections, in particular, have drawn comparisons to the 1800 presidential race. That’s because negativity has been on the rise in recent years.

Lovett points to data showing that, in every presidential election cycle from 2000 to 2012, campaign advertising, in aggregate, was more negative than in the previous one.

The 2012 clash between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney was the gold standard for negativity. In that race, almost 90 percent of ads were negative, meaning that the ad mentioned the candidate’s opponent. Between June 1 and Election Day, 64 percent of the ads aired were “purely negative,” meaning that only the opponent’s name was mentioned.

“The rise in negativity is probably correlated with changes in outside funding, though that is not yet clear,” says Lovett. He speculates there are most likely several factors at work, including a general increase in spending and increasingly conflict-oriented media coverage.

One thing that is clear is that, while the 2016 presidential contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton has been strikingly contentious, the campaigns have actually run fewer negative ads in the last month than their counterparts in the 2012 presidential race. But that’s in large part because they are only running about half the number of ads. Candidates are relying less on paid advertising, and more on social media, to get their messages out. Trump has nearly 13 million followers on Twitter, and Clinton has 10 million.

Tone of the Presidential Race Over Time

“Trump especially has relied on social media and engagement with media outlets to get his message out there,” Lovett says. “My guess is traditional campaign managers would say he’s killing himself with this strategy. He says what he thinks. That’s both his appeal and his downside.”

Clinton has used Trump’s own words against him in television ads. “On the margin, I think they’re effective,” Lovett says of the ads. “A lot of what Clinton says about Trump is reinforced by his own statements.”

He adds that Clinton has “some weak spots,” and those have “gotten play for people on the Republican side, too.”

No matter the content of an ad, repetition is key.

“People often forget the source,” Lovett says, “and after many repetitions, they may start to believe the message simply because they keep hearing it.”

The Daisy ad

The “Daisy” ad is perhaps the most famous negative ad in modern American politics. Created for Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 presidential campaign, the black-and-white ad ran only once. Yet it has become an iconic blueprint for campaigns seeking to strike fear in voters.

Johnson’s rival, Barry Goldwater, was considered a hawk, and the ad preyed on voters’ fears that he might not have the temperament to have access to the nuclear codes. The Clinton campaign has aired an ad showing a clip from this famous 1964 spot, in an effort to make the same argument about Trump.