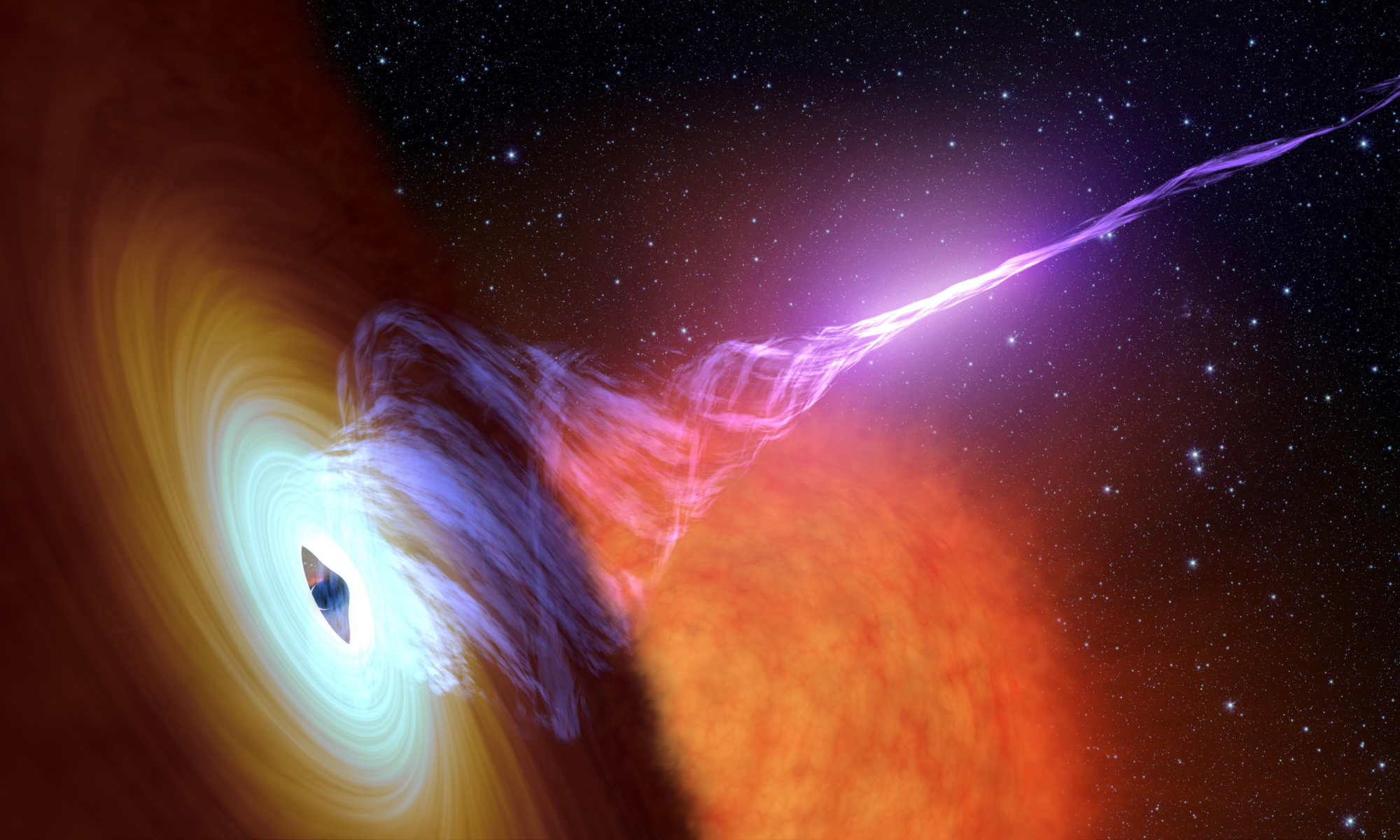

The universe is filled with magnetic fields; and how it got that way has long been a mystery. To explain the magnetization of the universe—or, rather, how tiny, primordial “seed” fields grew to astronomical proportions—scientists proposed the existence of a phenomenon called “turbulent dynamo.”

The phenomenon has remained elusive, however, never before actually measured or observed directly—until recently, when an international group of scientists from universities and laboratories across the globe, including the University of Rochester, demonstrated its existence through a series of experiments carried out on the OMEGA laser at Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE). The group reported their findings in an article in Nature Communications.

“Studying turbulent dynamo can help us understand how the universe was formed and how energy is partitioned within the universe,” says Dustin Froula, a senior scientist at Rochester’s laser lab and an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University.

What is ‘turbulent dynamo’?

A dynamo can be thought of like a rotating fluid, much like water spinning as it flows down a drain. If it were possible to attach a piece of string to water as it begins to rotate, the spinning motion would tie the string into knots.

Now imagine if the water represented a plasma—a form of matter where the electrons are no longer bound to their ions and that is typically found at very high temperatures—and the string represented the magnetic field lines. The tighter the knots—or rather, the circular motions of electrons—the stronger the magnetic field.

A decades-old theory

“Theoretical expectations that turbulent dynamo exists go back more than half a century,” says Gianluca Gregori, a professor of physics at the University of Oxford and the experimental lead of the project. “While significant theoretical work has been done over the years, demonstrating turbulent dynamo amplification in the laboratory remained elusive. It is extremely difficult to create on Earth the conditions in which turbulent dynamo can operate.”

To achieve these conditions, researchers used laser beams with the power equivalent to 100 trillion laser pointers. They leveraged the turbulent state of the universe’s visible matter by tapping into the energy of a plasma.

The challenge was to produce a plasma with high enough temperatures and strong enough turbulence that the turbulent dynamo mechanism could operate, and then retain this state for long enough that the mechanism could amplify seed magnetic fields.

Harnessing the power of Rochester’s OMEGA laser

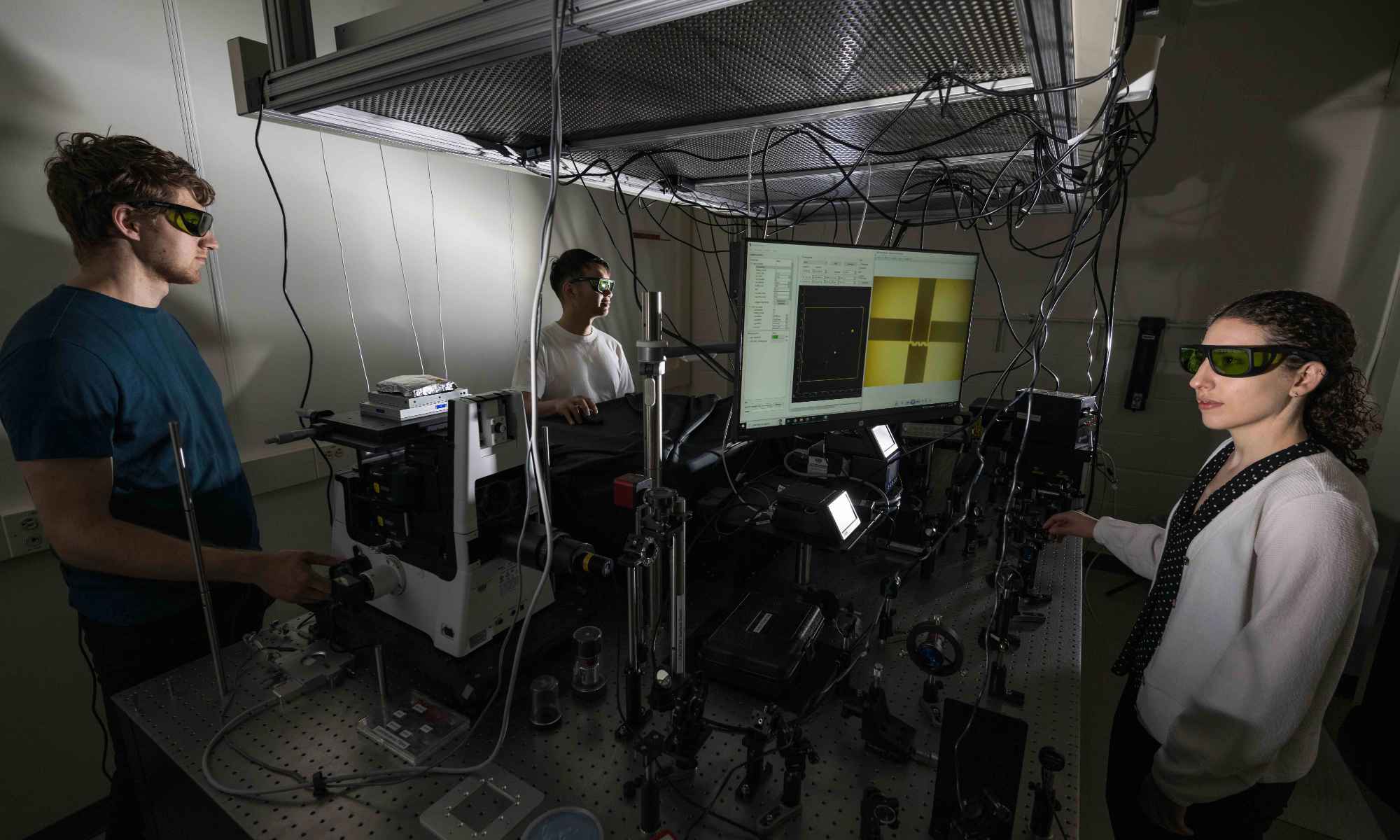

The collaboration included a five-year experimental effort to study magnetized turbulence in smaller-scale laser facilities and culminated in experiments at the Omega Laser Facility. The researchers measured the plasma temperature, turbulent velocities and magnetic fields using an innovative Thomson scattering system developed at the University of Rochester.

“Fundamentally, if you have a plasma and send laser beam light into the plasma, the plasma will scatter that light,” Froula says. “If you look at the frequency of the scattered light, it will have characteristics of the plasma. From those characteristics, we are able to measure the magnetic field strength.”

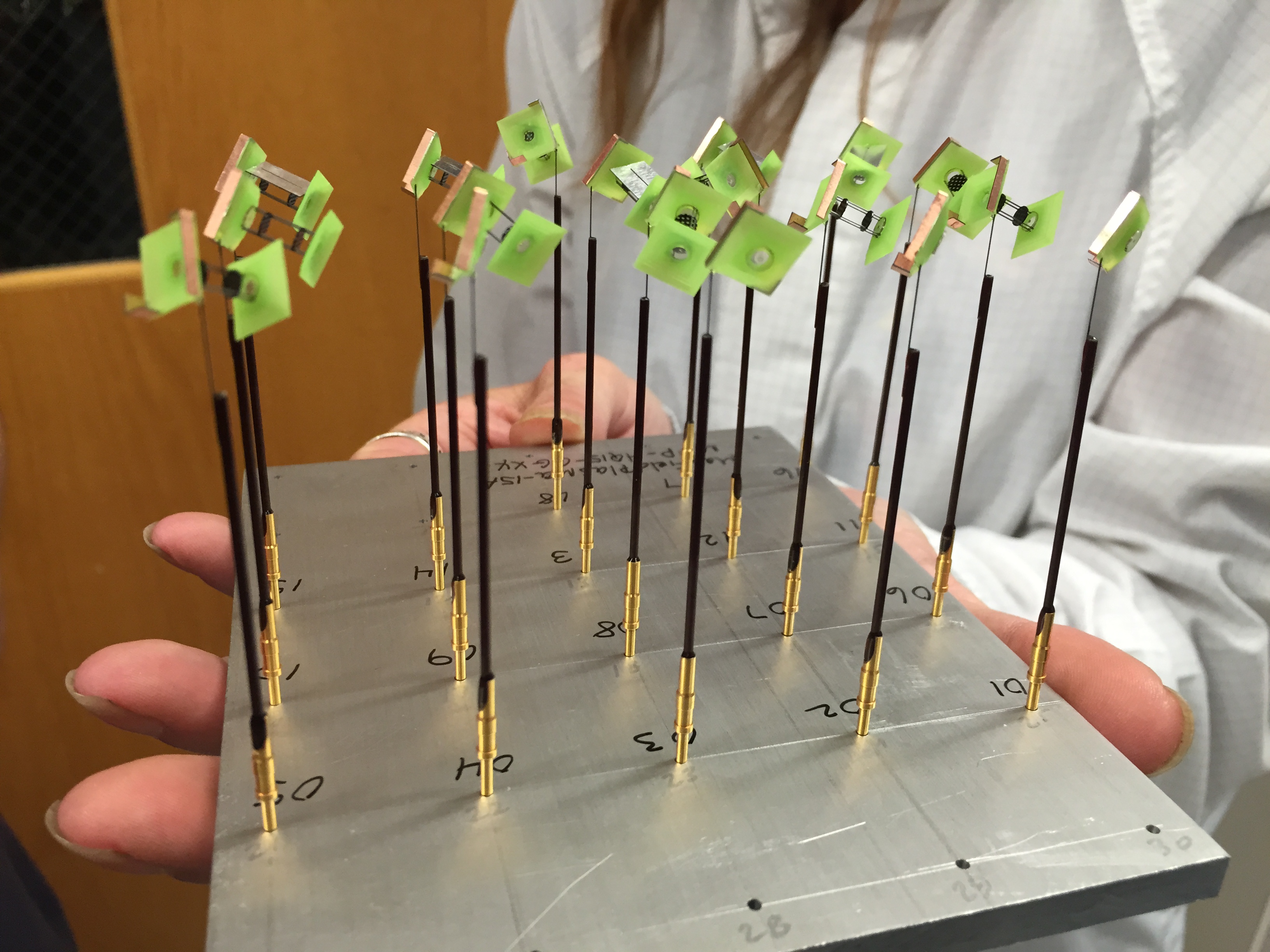

Innovations from other universities were critical components in the mix. In true collaborative fashion, the team performed numerical simulations to design and interpret the experiments using a FLASH simulation code developed at the University of Chicago; and they measured the magnetic field using protons fired through magnetized plasma, a technique developed by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Says Don Lamb, a professor emeritus of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Chicago, who has long been involved in research on turbulent dynamo and other mysteries of high-energy astrophysics: “The combination of numerical simulations using FLASH and the high laser power, high-shot rate and the wealth of diagnostics at the Omega Laser Facility at LLE made this breakthrough possible.”