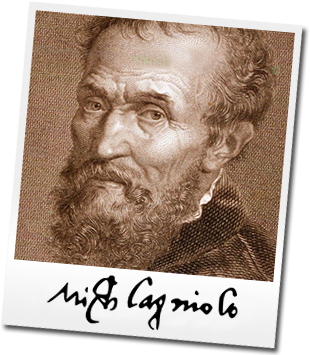

In his lifetime, artist Michelangelo was popularly known as “Il Divino”—“The Divine One.” The immensity of his talent seemed to put him beyond human categories.

But renowned Michelangelo expert William Wallace has spent his career trying to dispel that idea, helping readers to find the familiar in an extraordinary artist’s day-to-day life.

William Wallace on Michelangelo

Art historian William Wallace will deliver the keynote address for this year’s Ferrari Humanities Symposia on March 26 at 5 p.m. in the Hawkins-Carlson Room of Rush Rhees Library, on the University of Rochester’s River Campus. His talk, about the artist’s late years, is titled “Michelangelo, God’s Architect.” The event is free and open to the public.

On March 27, he’ll take part in a conversation at the Memorial Art Gallery with Jonathan Binstock, the Mary W. and Donald R. Clark Director of the MAG. “Michelangelo: Believe It or Not” will discuss the works that people have attributed to the artist and what these attributions reveal about their own eras. This event is free and open to the public; RSVP by calling 585-275-7393.

Wallace is this year’s Ferrari Humanities Symposia keynote speaker. The Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History at Washington University in St. Louis, he is the author and editor of seven books on Michelangelo, including San Lorenzo: The Genius as Entrepreneur (Cambridge University Press, 1994) and Discovering Michelangelo: The Art Lover’s Guide to Understanding Michelangelo’s Masterpieces (Rizzoli International Publications, 2012).

He’s been aided in his quest by the exceptional written record Michelangelo left.

“We know more about Michelangelo than probably any artist before the 18th or 19th century,” says Wallace. “Whereas Leonardo da Vinci wrote a lot in his notebooks, they’re primarily his own jottings and notes and sketches.”

But Michelangelo scholars have some 1,400 letters to consult, hundreds of them Michelangelo’s own. In his book Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man and His Times (Cambridge University Press, 2010), Wallace makes use of the 900 letters to the artist that have never been published in English.

“You get an incredibly richer view of the artist when you see the world that he operated in,” says Wallace. “He lived almost 90 years, and his letters are a cross-section of the 16th century.”

And because Michelangelo, unlike da Vinci, frequently worked in official capacities, he was enmeshed in the Italian Renaissance’s bureaucracy. “And bureaucracies keep records,” Wallace says.

The most widely known depiction of Michelangelo is Irving Stone’s 1961 novel, The Agony and the Ecstasy, which became an Oscar-nominated movie starring Charlton Heston in 1965. Stone’s treatment contrasts the ecstasy of Michelangelo’s artistic creation with the agony of a purportedly isolated life.

“I’ve worked very hard in my life to prove just the opposite,” says Wallace. “Yes, there were many times when Michelangelo fought with his family, and he had trouble with some of his workers. But it turns out that he was an enormously successful businessman. He was very loyal to his family—and saddened that he outlived every single member of his immediate family because he lived twice as long as most people did in the Renaissance.”

He made the most of his additional years by creating what was essentially a new career, turning to architecture in his 70s and 80s at the behest of Pope Paul III. Building St. Peter’s Basilica and six other major architectural projects brought Michelangelo into close collaboration with many others.

The results were profound: “He was helping to transform Rome into the city we know today,” says Wallace. The subject of his latest research is Michelangelo’s work in his final decades.

Five things you didn’t know about Michelangelo

He lived twice as long as other people of his day, and he ‘kind of knew everybody.’

While other artists, like Beethoven, are known for distinct early- and late-career styles, Wallace says that’s not the case with Michelangelo. “It’s not so much his artistic style that changes—it’s the kind of projects that he wants to undertake and carry out. His early career is fundamentally concentrated on heroic, large single-figure works that make his reputation: the Pietà, the David, the Sistine Chapel ceiling. These are the things that astonished the world and that he could claim he made entirely by himself. But his late career has very little of that. Instead, he devotes himself to these huge architectural projects that he knows he’s never going to live to finish.”

He managed hundreds who worked under him with efficiency and expertise, and he relied on others who’d long been loyal and close to him.

“Contrary to our received wisdom, Michelangelo never lived alone and always was working with people in collaboration. And this become ever-more true the longer he lived,” says Wallace. “Later in life, and certainly at St. Peter’s, he was working with a very large coterie of low-level workers—but also people he trusted to carry out his ideas and translate them into action.”

Wallace offers one other glimpse of the artist that may do even more to humanize him: Michelangelo loved a good joke.

“You never think of Michelangelo laughing. But he had a wonderful sense of humor,” he says. “He liked to laugh. Records show him becoming friendly with a large number of people largely because he just liked to hang out with them.”

About the Ferrari Humanities Symposia

University Trustee Bernard Ferrari ’70, ’74 (MD) and his wife, Linda Gaddis Ferrari, established the symposia to broaden the liberal education of Rochester’s undergraduates, enhance the experience of graduate students, and expand faculty connections with scholars around the world. The series was established in 2012, and has hosted speakers including Anthony Grafton, Stephen Greenblatt, and Jane Tylus. A full schedule for this year’s symposia is available here.