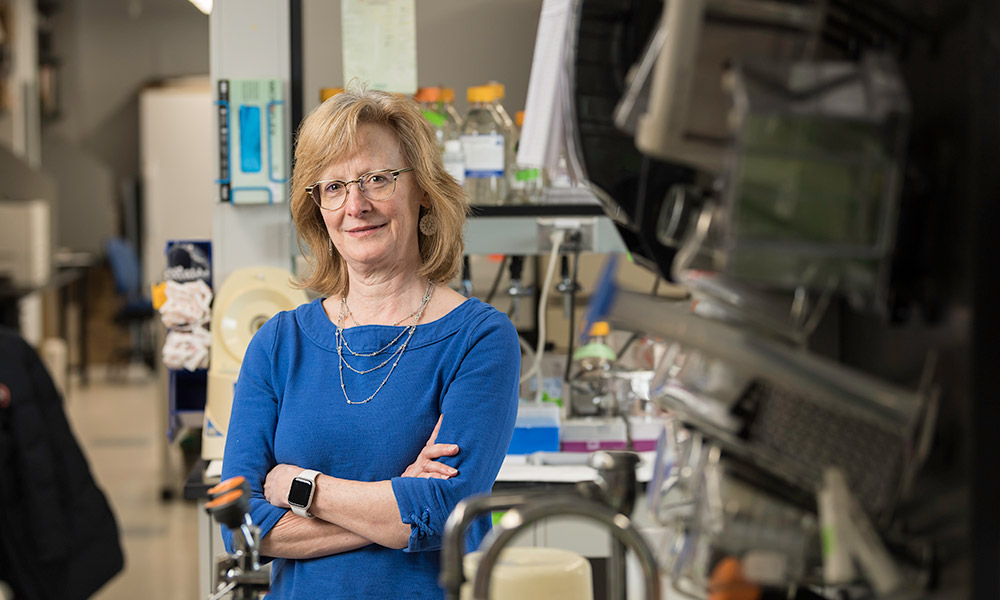

Women of Invention is a Newscenter series of profiles of women at the University who hold international patents. More than half of the University’s patent applications from 2011 to 2015 include women.

When it comes to research and invention, “there are lots of great questions,” says Lisa Beck, an internationally recognized expert in atopic dermatitis. “But not all of them have answers.”

And even when those questions do have answers, those answers may be lurking in unexpected places.

For example, atopic dermatitis, the most common form of eczema, is a chronic skin disease that causes unsightly lesions, profound itching, and outright misery for up to 20 percent of children and 9 percent of adults.

There is no known cure. However, Beck’s lab at the University of Rochester Medical Center discovered a defective protein that appears to be responsible for creating the “leaky” skin that causes the condition.

What’s leaky skin? It occurs when “water comes out, which makes the skin dry, and allergens, microbes, and irritants get in and cause the characteristic inflammation of the disease,” says Beck, a Dean’s Professor of Dermatology. “And it makes you very allergy prone.”

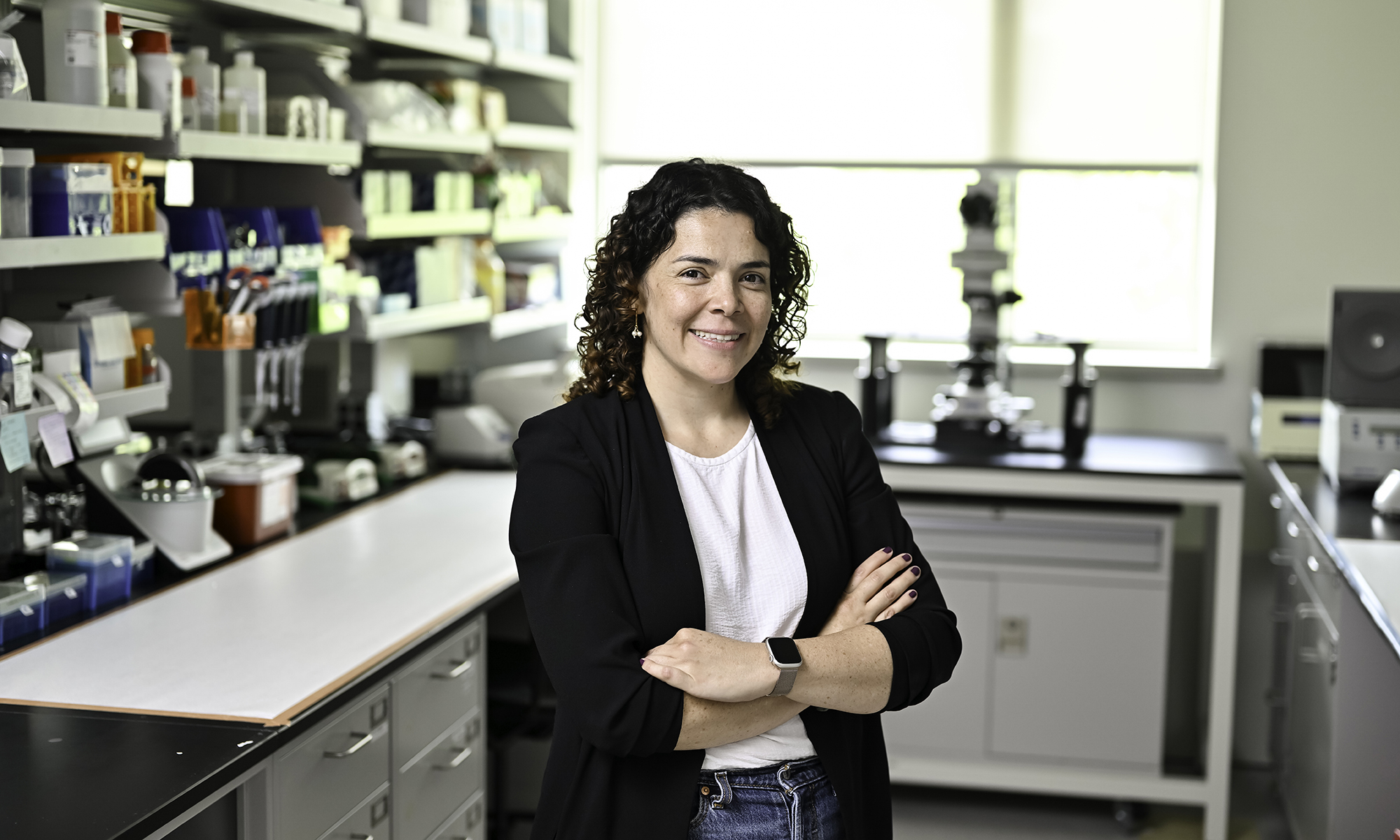

Her discovery of the defective protein may eventually lead to new ways to treat atopic dermatitis. But in the meantime, Beck and her collaborators—Ben Miller, also a professor of dermatology, and Anna De Benedetto, formerly at Rochester, now associate professor of dermatology at the University of Florida—have found a peptide that can temporarily “recreate” the same effect of having a faulty protein in healthy people as well.

That may not seem particularly helpful at first glance. But applied as part of a small wearable patch, the peptide can temporarily create temporary “leaks” in a very localized area of healthy skin. In doing so, it creates a perfect portal for vaccinating people or as an alternative route for drug delivery.

A winding route to dermatology

Beck’s first research project—for AP biology in high school—took place in the basement of her family’s home in Portville, New York.

The small town “has one stoplight,” says Beck. Her high school graduating class numbered just over 90, and just under half of the students went directly to college.

“And yet, we had national merit scholar finalists, so it was really one of those amazing public schools,” she says. Two of her teachers, one in biology, the other in math, “were pretty seminal in my education. To this day, they remain some of my best teachers.”

Education “was extremely important” to her father, a dermatologist, and her mother, who headed the medical social work department at a nearby hospital. Her father, in fact, was her first “collaborator” on that high school science project, and they also worked together on multiple carpentry and plumbing projects around the house.

She graduated from Mount Holyoke College, the elite liberal arts college for women, with a degree in chemistry. But not before spending her junior year at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville. She wanted to experience the atmosphere of a big university with a Division I sports program.

After watching Ralph Sampson, the celebrated 7-foot-4 center, play there, she became a lifelong fan of ACC basketball.

More importantly, she aced her classes.

“I wanted the guys to know ‘I’m a woman in STEM, and I can do physical chemistry just as well as you can,’” Beck says.

Her sights were set on going to medical school and becoming a general internist. However, by her second year of medical school at SUNY–Stony Brook, Beck was seriously questioning if she had made the right career choice.

“It was like feeding from a firehose—the amount of information and facts they give you in the first two years of medical school—and they never ask you to use those facts to help solve complex problems, which was what I had been trained to do at Mount Holyoke,” Beck says.

She decided to complete medical school, and came to Rochester for her internship and residency in the mid-1980s. Because there were so few critical care nursing home facilities at that time, hospitals cared for large numbers of terminally-ill, elderly patients. Many of those patients had dementia and would likely be in nursing facilities today.

To Beck, the situation presented a moral dilemma. “Should we be as aggressive working up a fever spike in a noncommunicative, 90-year-old woman, as we would do for a 20-year-old?” she asks. “Especially when that workup included invasive and painful procedures like a lumbar puncture, tons of bloodwork, a chest x-ray, and urine culture. It felt like we were doing more harm than good.”

Career changing advice

As chance would have it, the acting chair of medicine that Beck turned to for advice was Lowell Goldsmith, founder of the Dermatology Division at Rochester and a “giant” in the field.

“I had always teased my dad that a dermatologist wasn’t a ‘real’ doctor,” Beck says. “Because I really thought—and still believe—that the internists and pediatricians and family practitioners are the real unsung heroes in health care.”

But after talking with Goldsmith, Beck became convinced that she would be happier pursuing a career in dermatology, where the diagnoses rely on careful histories and physical exams.

She moved to Duke to complete a residency in the field—taking full of advantage of the free tickets available to dermatology residents to watch home games of the highly ranked Duke basketball team in Cameron stadium.

Beck then took her first faculty position at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. She solidified her clinical knowledge as head of dermatology at the university’s Bayview campus. But she spent most of her 17 years at Hopkins in the Division of Allergy, learning what it takes to be a skilled researcher from some of the best in their field.

“At that point, the allergy division at Johns Hopkins was the largest in the world,” Beck says.

“We had many weekly conferences, and that’s when I learned that you go to every research meeting, whether or not it has anything to do with what you’re working on, because that’s where you get creative new ideas.”

She also learned the importance of feedback from peers—however stinging it might feel at the time.

“You would be criticized quite robustly by your peers there, because the feeling was, ‘if we’re hard on you, when you’re ready to go out and present your work to the world, you’ll already have addressed the weaknesses.’”

A skin patch with global applications

And now Beck is back at Rochester.

The skin patch she developed with Miller and De Benedetto to deliver vaccines has worked in tissue cultures and in mice thanks to the hard work of Matt Brewer, a postdoc in the Miller and Beck labs.

“And the beauty of it is, when you remove the patch after 24 hours, the skin barrier recovers very nicely,” she says.

The novel technology could make it much easier to vaccinate entire populations in hard-pressed developing countries against yellow fever, malaria, West Nile, Zika, and Chikungunya.

Think of it: vaccination without the burden of hypodermics, which are painful, require expensive biohazard disposal, and highly trained health care workers.

Patents are now pending in the US and overseas.

Not bad for someone who worried in medical school that she “wasn’t helping anyone.” Now, Beck has come up with a technology that could help people on a global scale.