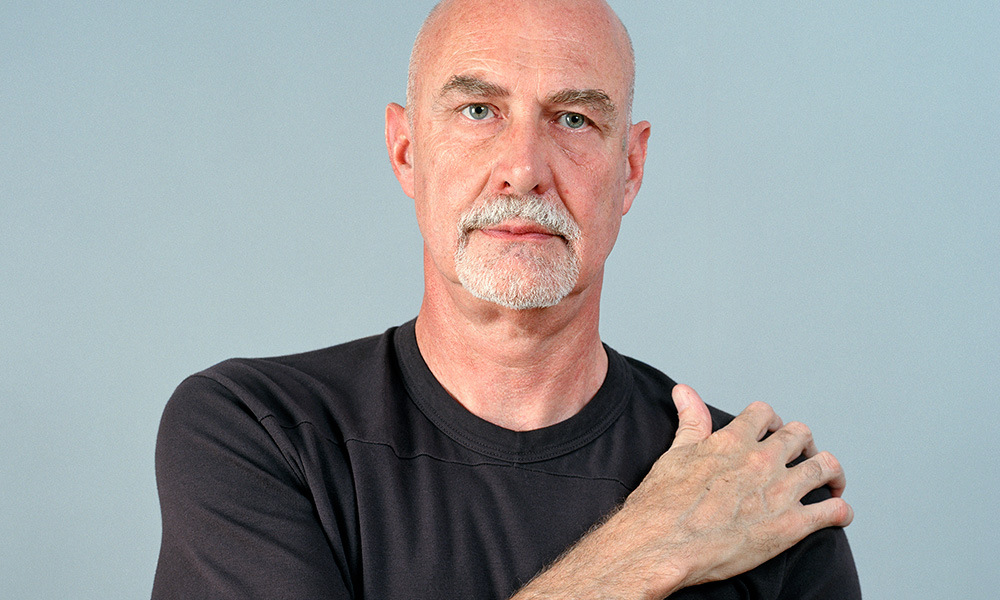

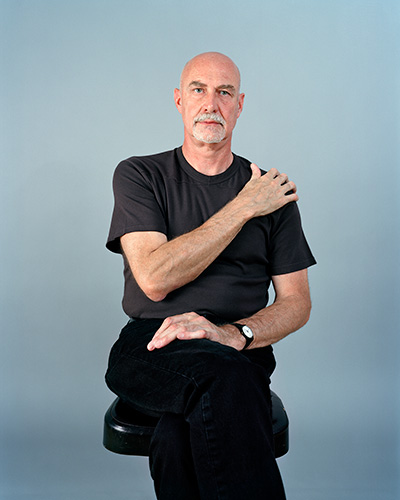

An internationally renowned art and cultural critic, theorist, curator, and activist, Douglas Crimp—the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies at the University of Rochester—created work important to thinkers across the arts and humanities. Those who knew him say his intellectual nimbleness and acumen were matched only by his gentle kindness and generosity.

Crimp died on July 5, at age 74. He was a “towering figure in many fields,” says Jonathan Binstock, the Mary W. and Donald R. Clark Director of the University’s Memorial Art Gallery. “Photography, dance, and visual forms of political activism are only a few of the areas where his influence was, and remains, global and profound.”

Born and raised in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, Crimp studied art history as an undergraduate at Tulane. After graduating in 1968, he moved to New York City, where he found himself at a convergence point of contemporary art and gay culture. His experiences were the subject of his 2016 book, Before Pictures (University of Chicago Press). The book “moves from anecdote to criticism to research, back to anecdote, and so forth, and also from my gay life to my art world life,” he told Rochester Review in 2017. But he resisted those who termed the work a memoir; its focus was on the historical moment and what he called the division “between the art world and the queer world.” The book concludes with his curation of the exhibition Pictures at the gallery Artists Space in 1977, a show that made him famous.

Crimp remained an important part of the New York art community for the rest of his life. As recently as 2015, he worked with the Museum of Modern Art as part of the curatorial team for its exhibition Greater New York. “Crimp’s influence has been vast,” Alex Greenberger, senior editor of the magazine ARTnews, wrote in an obituary. “It has become impossible to write the history of postmodern art without referring at least once to his criticism.”

Crimp’s view of art history wasn’t traditional. He rejected the Romantic ideal of the solitary genius, considering instead the context in which the artist emerged and worked. Pictures brought together artists such as Cindy Sherman, Robert Longo, and Laurie Anderson, whose works reflect their upbringing in a media-saturated, consumerist world. Different generations have different relationships to art and culture, Crimp argued, and he was one of the first critics to take note of what later became known as the “Pictures Generation.” The Museum of Modern Art mounted The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984 in 2009, a show that used Crimp’s exhibition as its foundation.

“Douglas insisted that art history, and the museum along with it, needed to change,” says Sharon Willis, a professor of art and art history, and of visual and cultural studies. Crimp was an influential practitioner of institutional critique—viewing museums, galleries, and other arts institutions as a kind of “frame” for art, driven by ideological principles of curation, rather than as a neutral venue. He collected his essays on the institutions and politics of contemporary art in his book On the Museum’s Ruins (MIT Press, 1993).

Between 1977 and 1990, Crimp edited the contemporary art criticism and theory journal October, published by MIT Press. “The work that he did in October was absolutely field shaping. That remains a cutting-edge journal, but he was there on the ground floor,” says Willis. When Crimp decided in the 1980s to devote an issue to the role of art in confronting the AIDS crisis, he first immersed himself in the lives of the people on the front lines of a battle over politics and public policy.

“Immediately, I started going to ACT UP meetings—the activist organization—to learn about the crisis in order to properly do a special issue of a magazine. And that just pulled me right into the activist movement,” Crimp said in a 2014 University of Rochester video. He published the October special issue, AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Criticism, in 1987. It offered a series of critical essays on the culture of the disease. MIT Press republished the essays a year later, the first book-length treatment of the cultural meaning of AIDS.

Others at the time contended that the suffering caused by AIDS could inspire art, but that art itself had no role to play in fighting the epidemic. Crimp disagreed, calling for an “activist aesthetic practice,” in which art could help save lives by intervening in the social world. “We don’t need to transcend the epidemic; we need to end it,” he wrote in 1987.

Crimp’s thinking about museums and performance was never bound by convention. But in response to the AIDS crisis, he developed a more insistent frame of mind. “What he was prescriptive about was an entire community being erased by AIDS,” says Rachel Haidu, an associate professor of art history and chair of the department. “That was his most dogmatic moment. He said, in effect, ‘This has to be the most pressing concern.’” Crimp collected his writings on AIDS in his book Melancholia and Moralism: Essays on AIDS and Queer Politics (MIT Press, 2002).

When he arrived at Rochester in 1992—first as a visiting professor, while completing his PhD in art history at CUNY Graduate Center—Crimp had already pivoted away from art history toward cultural studies, a change driven by his experiences as an AIDS activist. He took a position with Rochester’s Visual and Cultural Studies program (VCS). Established in 1988, VCS is an interdisciplinary doctoral program that brings together students and faculty from art and art history, film studies, English, modern languages and cultures, music, and anthropology. Crimp was appointed as a professor of art history and visual and cultural studies in 1996 and became the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History in 2003. He served as the acting codirector of VCS from 2002 to 2005.

“Douglas’s tripartite career as a scholar, activist, and critic helped shape the type of work that VCS became known for,” says Joan Saab, an associate professor of art history and visual and cultural studies. Now vice provost of academic affairs, she’s a former director of VCS. Crimp began by working on postmodern art and photography; in his late career, he was working on criticism of dance and other modes of performance, she notes. “As the terrain evolved—in no small part, through his influence—Douglas evolved, too.”

One of the last students to defend a dissertation under Crimp’s guidance was Tiffany Barber ’16 (PhD), now an assistant professor of Africana studies at the University of Delaware. Though she earned a BFA in dance at the Ailey School at Fordham University, she never anticipated that dance could become an essential part of her scholarship. The fact that it has is a testament to Crimp’s own investment and vision, she says: “The way that he practiced visual analysis in terms of being invested and having stakes in your work translated into bringing that out in his students, too. ‘What are you passionate about? What objects call to you—and what are they doing in the world? How do they make you see the world differently?’”

Crimp modeled a kind of “scholarly possibility” for students, says Saab, “a way of doing things that was in the world, not just in the library or in the museum.” And he did so, colleagues and former students note, through writing that was consistently arresting in its beauty—a compliment not often paid to theoretical or academic prose.

“I’d have students ask me to read their work before they showed it to Douglas,” says Saab. “He brought that out in people, the desire to be their best.”

While he was indisputably an academic star, Crimp’s demeanor was humble and generous. “It’s not often that a truly internationally eminent scholar, who is so much older than his students, is able to treat them as important upcoming intellectuals in their own right,” says Janet Berlo, a professor of art history and visual and cultural studies. But Crimp did.

“As giant and influential as he was, he was also endearingly shy,” says Barber. “He had an incredible attention to detail and warmth that came out in different activities, like getting people together to see dance, to be in the audience, looking at a performance—that was one of the things he loved to do. Or baking. Just things that were so simple but brought people together to have interesting conversations.”

When Berlo joined the faculty, she was daunted by Crimp’s presence, but he quickly dismantled her apprehensions.

“His office was across the hall from mine then, on the fourth floor of Morey Hall. He often baked in the evenings, as he did the readings he had assigned for his seminars, and he would appear at my office door, a plate of cookies supported by one of his extraordinarily large and elegant hands, and offer me one. It was completely disarming, and I realized I had no reason to be intimidated by him.”

“Friendship and art,” says Haidu, “were the two ways he lived.”