Molly Ball, a lecturer, and Pablo Miguel Sierra Silva, an assistant professor, have been married for nearly ten years. Their three children, aged 2, 5, and 8, are spaced apart in near-perfect three-year intervals. While both teach in the Department of History at the University of Rochester, they seem to work in almost opposite shifts: when one parent leaves for the University’s River Campus, the other one takes charge of the kids when they’re not at daycare, kindergarten, or school.

In many ways, their lives before the COVID-19 pandemic resembled a choreographed dance, designed to prevent a collision between the private and the professional. But in the face of the virus, that carefully calibrated construct has come crashing down, as it did for hundreds of thousands of families around the globe.

“The first week was brutal, absolutely brutal,” admits Sierra Silva.

Video Feature: Faculty perspectives on remote teaching

What’s it like to teach remotely? Rochester faculty members share their experiences of moving classes online this spring.

Having had to redesign syllabi and learn how to use new online teaching tools—while simultaneously trying to keep their kids’ education on track and keep them happy to boot—proved challenging.

Things began to look up once the couple settled on a new routine.

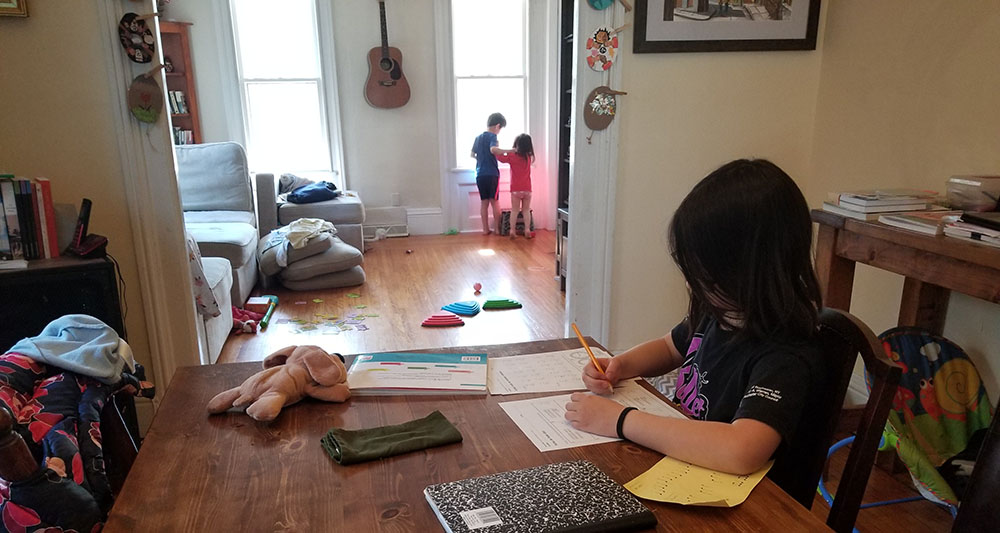

Now Ball and Sierra Silva have split their green, two-story house—built in 1876 in Rochester’s Southwedge district—into two zones. From 8:30 a.m. to about 5 p.m., the upstairs becomes “la uni chiquita”—as their kids, who are raised bilingually, have termed the no-go zone at the other end of the flight of stairs. Downstairs, the dining room turns into a home school and kids area.

“The heavy sidewalk and road construction on our street has become the new center of excitement,” says Ball.

“We invite them to not have temper tantrums when we are upstairs at the little university,” explains Sierra Silva. Ball laughs.

The two historians have returned to a shift system. At any given time, one parent is in charge of the happenings downstairs while the other one teaches or advises students upstairs. Grading has been relegated to late night when the children are asleep. On top of course preparations, Ball now spends Sunday nights planning their children’s lessons for the week on PowerPoint and prints them out. Reams of school materials are sorted into daily packets for each child.

Their workdays have undoubtedly grown longer, as has everyone’s hair.

Transitioning to online teaching

Ball, whose specialty is Brazil, and Sierra Silva, whose research focus is Mexico, met as graduate students at UCLA. Both are avid sports fans and spent years dreaming up a course teaching the history of Latin America through soccer. Besides entertaining fans, soccer has been successfully used across Latin America to fabricate national identities and promote multi-racial societies, but has also helped bolster dictatorships, drug trafficking, and misogyny.

Sierra Silva finally designed and taught the course in fall of 2014 in the wake of the World Cup in Brazil and has also been teaching a version of the class this spring. Transitioning the course onto a virtual platform required considerable work.

An easy switch, however, was the new wear-your-favorite-jersey-to-class policy.

Ordinarily, Sierra Silva, who was born in Mexico, roots for the Mexico City-based Club América FC and the Mexican national team. Internationally, he follows whichever premier league football team has the best Mexican striker on its roster. That would be the Wolverhampton Wolves right now.

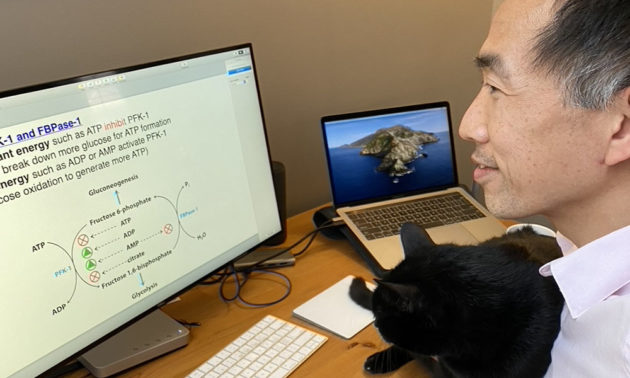

On this particular day, however, he wears the Spanish national team’s black polo shirt.

“I wear this on my more somber days,” Sierra Silva says, half joking. “We did a heavy lecture today and so I thought this all-black look would work very well.”

Prior to teaching from home, he used to dole out primary documents and break his students up into groups to represent different parts of society. He enjoyed being able to move freely around the classroom from one group to the next.

“That dynamic has proven a challenge to recreate in a digital medium,” he says.

But there are upsides. His advanced seminar transitioned well to online teaching and, to his surprise, the students appeared to prepare more for class. Maybe it’s the side-effect of knowing that the camera is on and they’ll have their peers’ full attention, he muses.

For Ball the move to online was tricky at first. Both of her courses—Immigration in the Americas and Public History: Theory and Practice (co-taught with Michael Jarvis, an associate professor of history)—had been designed for community engagement and involved community partners and trips to off-campus sites. Now Ball, Jarvis, and her students have moved toward creating a website instead.

Yet the virus is never far off.

“Some of my students are at the epicenter of the pandemic and are really trying to manage family crises. That’s made things certainly more complicated for teaching,” Ball says.

Meanwhile, she has restructured her immigration course to use more online sources, such as digital archives. Ball says she’s excited when certain aspects of the course end up working better online—such as moments in smaller breakout Zoom groups— than in the traditional classroom setting. She’s found another silver lining: asking students to post their thoughts about the day’s readings and class activities on the class discussion board at the end of the week has resulted in more insightful posts. “If we did all that in a true classroom you would lose those moments of reflection,” Ball says. Instead, she says, the online reflections have become more nuanced once students have had time to think about what was taught in the weekly Zoom sessions.

Sierra Silva, for his part, has been encouraging his students to use digital sources for their research projects. Without access to the stacks and printed materials, the class has reacted by “mining that enormous archive” of sporting information that YouTube represents.

“What’s really interesting is that when you start looking for the impact of sport on society you start finding it in places you wouldn’t expect,” he notes. “Some information is only visible when you’re willing to engage film and documentaries and that’s something that I don’t typically do with my courses but am now forced to.”

Ball and Sierra Silva pause and notice the silence in the house.

“Something has been destroyed, or short circuited,” Sierra Silva says. “Something bad has happened.”

“I think that they have shifted probably to a YouTube show we don’t love,” adds Ball, with a degree of resignation. “But as an upside, the three of them have become very close in all of this, and that’s really nice to see.”

And the youngest has been potty trained ahead of schedule, says Sierra Silva triumphantly.

Read more

Teaching a large lab class—virtually

Teaching a large lab class—virtuallyBiology professors Dragony Fu and Alexis Stein have creatively adapted a 250-plus-student class—with a lab—to a virtual environment.

We’re all in this together

We’re all in this togetherA few of the undergraduates who have been studying remotely since March talk about the transition and what it’s meant for them.

Still serving students—and missing the ones who are gone

Still serving students—and missing the ones who are goneDining Services has adjusted its services and options to accommodate the approximately 750 students who remain in the residence halls on the River Campus during the COVID-19 pandemic.