The fourth-generation teacher is always searching for the ‘transformative potential of education’ in classes.

What they’re saying

“Will is a deep thinker on pedagogical challenges facing all of us who teach in the humanities, namely, how to best articulate and demonstrate the value of humanistic inquiry. His article ‘The Tragedy before the Blood Commons: Araki Tetsurō, the Crisis in the Humanity, and Animated Education’ is a creative and provocative refutation in the context of Japanese literature and anime of the cultural narrative of worthless humanities majors. The humanities need such eloquent defenders like Will to remind those who have forgotten that the humanistic arts were the first and best ways of exploring and understanding the human experience.”

—John Givens, chair, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures

“The two classes I took with Professor Bridges were vastly different in size, but in both cases he created an open discussion while masterfully guiding us towards deeper insights and revelations. This is a hallmark of his teaching style. The ‘point’ is never forced upon the class, which keeps participation open to all ideas, however varied they may be.”

—Alex Velberg ’21

“Class was always diverse. We often worked and discussed in small groups, we shared our ideas on online discussion threads to encourage discussion and, as Prof. Bridges said, to encourage those who might not want to speak in class to have another channel to interact and discuss. In each class I took with Prof. Bridges, I knew everyone’s name because everyone wanted to participate, and he would always call us by name.”

—Cherish Blackman ’18

As a fourth-generation teacher, Will Bridges jokes that the profession is something his family “just can’t shake.” But he’s serious about its impact.

“The transformative potential of education is one of the reasons I pursued this career,” he says.

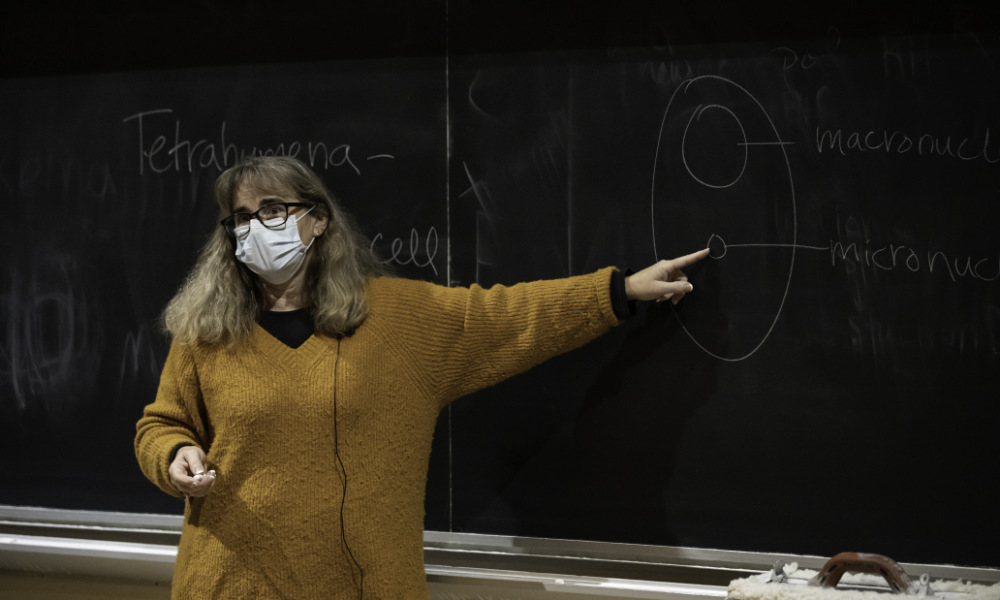

An associate professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, Bridges teaches modern and contemporary Japanese literature and culture, comparative literature and literary theory, and African American studies. In his four years at University of Rochester, he has honed his craft with vigor, always searching for innovative ways to reach students. It’s a major reason why he’s a recipient of this year’s Goergen Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching.

“I see my job as expanding that sense of what can possibly be,” he says. “A professor is just an intellectual tool, one to sharpen and polish your mind. It’s up to students to determine how best to use that tool regarding their personal, professional, and societal goals.”

Bridges’ teaching is rooted in three principles:

- Immersive education: As an assistant professor of Japanese at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, he created a study abroad program to Tokyo, and used an online platform to create a virtual Kyoto for those who couldn’t travel. He also prepared campus-wide scavenger hunts and dodgeball matches for students in which they could only communicate speaking Japanese.

- Humanities as a pragmatic endeavor: Bridges has developed and proposed a new minor at Rochester called “imagination and forethought,” which would introduce students to the dynamic field of futures studies. ”Just as history teaches us to imagine and understand the past, futures studies teaches us how to better imagine and understand possible futures,” he says. “The future is open to any number of possible outcomes. How might we best determine a path forward given all those possibilities?” The minor has received cross-listing approval from the chairs of 12 College departments and has been forwarded to the College Curriculum Committee.

- Teaching as an exercise in community building: For his Poetry and Japanese Calligraphy class, Bridges created a workshop in which students teach the basics of calligraphy to students at the nearby Rochester Institute of Technology. “Rather than having the study of calligraphy end in the classroom, those RIT students become de facto members of the classroom community,” Bridges says.

Bridges grew up in Texas and developed an interest in Japanese culture from a young age. “In elementary school, I did this science fair project on the atomic bomb and the damage that could be done to the human body depending on the distance from the epicenter,” he says. “Such a morbid thing for a kid that age to be interested in. I was fascinated by the remarkable resilience and revival that happened in post-World War II Japan.”

That led to a passion for post-World War II Japanese literature. “You have this body of authors who are really wrestling with two things,” he says. “First, their responsibility for what happened during World War II. The Japanese government was good at coercing authors to be a part of a cultural propaganda machine. Second, this genuine sense of the idea of democracy and freedom of expression that the Allies are writing into their postwar constitutions.”

Bridges says the number of postwar Japanese novels a student can read during a semester is limited relative to other Japanese media, such as film and television animation, known as anime. The students in his Life and Anime class have “watched so many, they could come up with 20 different anime to compare,” he says. “That deep familiarly with the medium lent itself to less of the student-teacher model and more of a learning community model. They know as much or more about anime as I do. All I need to do is stop talking and let them start talking.”

In that same class, Bridges assigns students to groups for the final quarter of the semester in which they create the syllabus—“the best part of the class,” Bridges says. Students select anime and design the lesson plan and activities.

He also allows self-grading (for about a quarter of the final grade) in some classes. Students assign their grades through a written self-reflection, where they can provide an honest assessment of their class efforts. “It’s about having students develop a sense of ownership over their educational navigation of the University,” Bridges says. “Self-grading puts a framework around that importance.”

Bridges was on leave from teaching when the COVID-19 pandemic forced the University to close its doors in March 2020. But when he began teaching in a hybrid format during the 2020–21 academic year, he held onto the most elementary—and important—principle he learned when first starting out.

“This is someone’s child, and they’ve entrusted us with their child,” he says. “There’s an ethics of care that should be at the foundation of any classroom. Any rubric I was using to grade students was completely overhauled with the emphasis on what would be best for the wellbeing of the student. That is my mantra.”