Rochester historian explains how Ukraine history is intertwined with Russia’s—but also with that of many other nations, empires, ethnicities, and religions.

“It’s a complicated history. But I want to be clear that what’s going on in Ukraine now is a brutal act of aggression with absolutely no justification,” says Matthew Lenoe, an associate professor of history at the University of Rochester, who is an expert on Russian and Soviet history, Stalinist culture and politics, the history of mass media, and Soviet soldiers in World War II.

Rochester voices: Washington Post

In an analysis for the publication’s “Made by History” section, Matthew Lenoe explains the dangers of mistakenly blaming Putin’s invasion on the “Third Rome” concept.

- Read the article online at the Washington Post (subscription required) or MSN.

While the history of the Ukrainian state probably cannot be traced back any earlier than 1918, Lenoe says “to be clear—today Ukraine is a nation state” where polling in elections indicates that the “vast majority of Ukrainians” want to preserve their independence.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has made several dubious historical arguments, most notably in his 5,000-word essay “On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” published on the Kremlin’s website in July 2021. In it, he elaborates on his assertion that Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” as a precursor to and defense of Ukraine’s invasion.

For instance, Putin claims that Ukraine didn’t exist as a separate state and had never been a nation. Instead, he argues, Ukrainian nationality was always an integral part of a triune nationality: Russian, Belorussian, and Ukrainian. Putin also writes that Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians share a common heritage—the heritage of a realm known as Kievan Rus (862–1242), which was a loose medieval political federation located in modern-day Belarus, Ukraine, and part of Russia.

“When Putin says this is the heritage of these three Slavic peoples—in one sense, he’s not wrong. But there’s no continuous line to be traced from this loose river confederation to the Russian state. And there’s also no continuous line to be traced from this loose confederation to the Ukrainian state,” says Lenoe, who is the author of Closer to the Masses: Stalinist Culture, Social Revolution, and Soviet Newspapers (Harvard University Press, 2004) and The Kirov Murder and Soviet History (Yale University Press, 2010). He is currently finishing his third book, tentatively titled Emotions, Experience, and Apocalypse in the Red Army, 1941–1942.

Support available in response to Ukraine crisis

The war in Ukraine is generating fear, worry, and grief throughout the University community—especially for those whose families, friends, and loved ones are affected. Faculty, staff, and students are encouraged to take advantage of available support and guidance.

Ukraine, for its part, also points in its declaration of independence to a continuously existing state from 1000 CE. Says Lenoe, “Today, both Russians and Ukrainians are making claims about their direct descent from Kievan Rus that are simply mythical and wrong.”

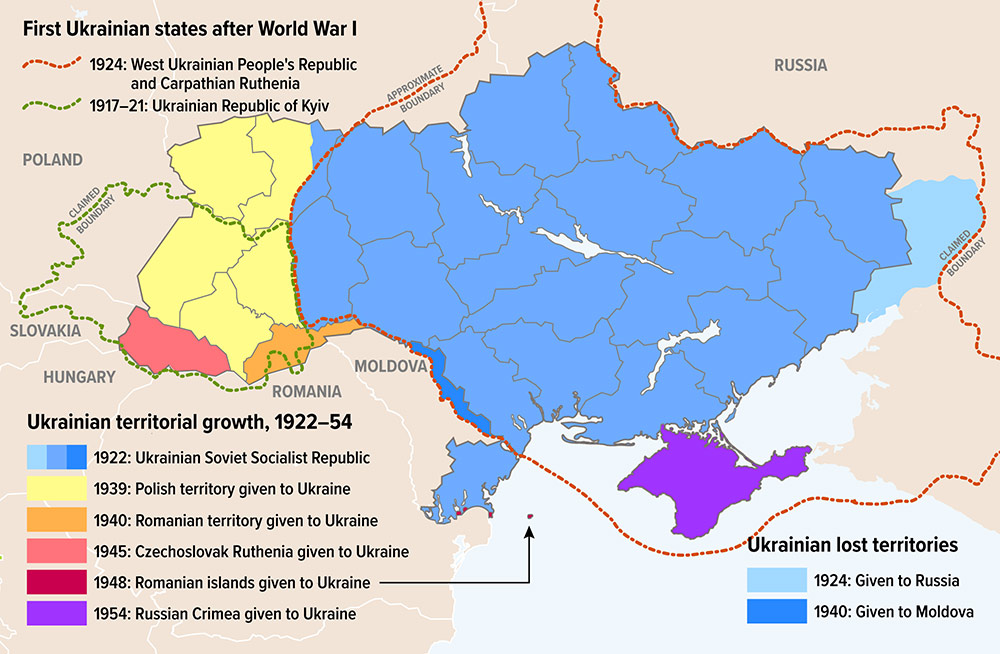

Over the course of centuries, the area that is today Ukraine has been alternatingly swallowed up, controlled, or taken over by the Mongol Empire, later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Empire, while Crimea was at one point a client state of the Ottoman Empire. Between the World Wars, portions of western Ukraine were ruled by Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia.

In short, Ukraine’s territorial and ethnic history is “complicated and complex,” Lenoe says. Of course, its history is closely intertwined with Russian history, he adds. But it’s also intertwined with Polish history, with the history of the Greek Orthodox Church, even Romanian history, and the history of the Turkic peoples on the Eurasian Steppe.

Here the Rochester historian fact-checks several of Putin’s historical claims and discusses the ideas of nationhood and statehood, particularly with regard to Ukraine.

Q&A with Matthew Lenoe

What do historians mean by “nation” or “nationhood”?

- Contrary to popular belief, a nation is not something that has existed for centuries or millennia, with its origins in the distant past.

Lenoe: Historians don’t think of nations as existing from time immemorial. Instead, nations emerge from a process that is sometimes very deliberate. Often the birth of a nation goes hand-in-hand with people’s increased literacy, the instituting of universal schooling; a state has defined boundaries, a central bureaucracy that is professionalized, and it is not the retinue of a noble. One of the legacies of the Enlightenment is the idea that every nation deserves a state.

When did Russia and Ukraine first emerge as states?

- The Russian state emerged around the 1450s. Ukraine as a state didn’t exist until the early 20th century.

Lenoe: The history of the Russian state, as opposed to the nation, can be traced back to roughly the 1450s in a principality called Muscovy. Meanwhile, the history of the Ukrainian state probably cannot be traced back any earlier than 1918. So, to say that there was a Ukrainian nation in 1000 CE is an anachronism. There was no Ukrainian nation, just as there was no Russian nation in 1000 CE.

Mass Ukrainian nationalism emerged out of the traumas of the 20th century. Like Ukraine, there are plenty of states in Europe now that don’t have a long tradition of statehood. Putin claims that there’s not a Ukrainian history separate from Russian. But that’s not true. Among the speakers of Ukrainian and in the lands now comprising Ukraine, there were many different experiences. They belonged at times to different states and realms. But there was interaction between Ukrainian speakers throughout much of this history, and they developed a common identity, especially after the mid-19th century.

What made Ukraine historically a place of “borders and mixing”?

- Ukraine is an area of various ethnicities, including nomads, absent of clear religious or physical boundaries.

Lenoe: The word “Ukraine” derives from a Slavic root, which can mean “frontier,” “edge,” “border,” or “outlands.” It has always been a place of borders and mixing, although the country itself didn’t exist yet, including the border between the steppe and the forest zone, which is extremely important in terms of the sorts of people who lived here. You have the mixing of many ethnicities: different Slavic ethnicities, Turkic peoples. Eventually, you get Jews, Germans, people who come to be called Poles, Greeks, people who spoke Iranian languages, and so on. Religious boundaries were equally fuzzy between the Orthodox Christian Church and the Catholic Christian Church, with Islam thrown in.

What role do the Cossacks play in Ukrainian history and statehood?

- Through rebellion, they established a Ukrainian Cossack state, the Cossack Hetmanate, that existed from 1648 to 1764.

Lenoe: The Cossacks were folks who lived in the steppe and started probably as multiethnic warrior bands; they pretty quickly became Orthodox and largely Slavs. They were fishermen or agriculturalists; they often lived on protected fortresses and rivers, and a lot of their living was made by raiding the Crimean Tartars and Ottomans.

The whole area of the steppe was known as the wild fields and was a kind of free zone. The Cossacks thought of themselves as free men. That’s very important. They practiced early on a form of warrior democracy. Controlling the steppe was something both Moscow and Poland wanted to do. And they both tried to use the Cossacks: Moscow hired them as mercenaries and supplied them with weapons, and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth would do the same.

Important to note is Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a Cossack who lead a rebellion against the Polish Commonwealth in 1648 and 1649 that resulted in the creation of a Ukrainian Cossack realm, known as the Hetmanate. You can’t quite trace the modern Ukrainian state to this, but Ukrainians remember it as an important part of their heritage. Khmelnytsky had to maneuver between Russia, Poland, and the Ottoman Empire to maintain independence. In the end, the Hetmanate threw in its lot with the Russians, under heavy pressure. Putin claims that the Russians “liberated” the Cossacks, but it was really a forced “choice.”

Putin claims that a separate Ukrainian identity is an artificial invention. Is he right?

- Putin is about a quarter right—in part because he is aware of modern scholarship on Ukrainian identity.

Lenoe: Putin is referring to a myth that a separate Ukrainian identity was created in the mid-1800s by Poles and a few “misguided” Ukrainian intellectuals.

Now, as with a lot of what Putin or somebody in his entourage says, he’s aware of certain kinds of modern scholarship. There’s a quarter truth here. In the mid-19th century, when intellectuals start debating identity and assemble a Ukrainian grammar, the peasants couldn’t have cared less: they were almost entirely illiterate, they would not have thought of themselves as Ukrainian, they would have thought of themselves as Orthodox people, identified by their village, maybe identified with their position in life—as a peasant or townsperson. And the same thing held for Russia, perhaps with the difference that after the Napoleonic invasion of 1812, nobles were starting to think of themselves strongly as Russian.

By 1816, you’ll find the beginnings of a written Ukrainian language, coupled with an increasing romantic interest in the Cossacks as noble pirates, adventurers, and fighters for freedom. And while the Cossacks are a memory that both Russians and Ukrainians share, they become central to Ukrainian identity. By the mid-19th century, you have intellectuals and writers, such as Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) and Mykola Kostomarov (1817–1885), drawing on what they see as a Ukrainian legacy that goes back to the Cossack Hetmanate and, indeed, they’re saying back to Kievan Rus. Contra Putin, these folks are not Poles, but Ukrainians living within the Russian Empire.

Kostomarov really is one of the founders of Ukrainian nationalism. His vision is interesting, because he was also what we might call a “liberal.” He said that the Ukrainian people are naturally free people, that they will win their freedom from the Russian Empire, and that they will lead the world’s peoples to freedom.

Putin claims that the German Empire and Austrian-Hungarian Empire essentially created a modern Ukraine. Is that true?

- The Central Powers were the World War I coalition that consisted primarily of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary. Putin’s claim that this coalition sponsored an independent Ukraine is wrong.

Lenoe: That’s basically a bunch of nonsense. Putin is basing that on the fact that Ukrainian leaders, at a particular moment, sought the support of the Central Powers to save their independence movement from the Bolsheviks. But at that point, there had been already a three-generation-long movement for Ukrainian autonomy or independence. So, this claim is nonsense.

Is modern Ukraine the product of the Bolshevik era, as Putin claims?

- Putin takes to an extreme the nuanced scholarship about the Soviets’ sponsoring different nationalities, including Ukraine, which later split from the Soviet Union.

Lenoe: Early Bolshevik nationalities policy actually sought to build different nations culturally, because they wanted to head off the threat of nationalism to Communist power. They wanted to make sure they didn’t incur nationalist rebellions. Rather than relying on brute force, the idea was to have different republics that would be politically controlled by Moscow but would have cultural autonomy. In a sense, you can talk about a continuous Ukrainian state from 1918 onward, because nominally Ukraine was a kind of sovereign state within the Soviet Federation.

Now, as we know, in a lot of ways that idea of autonomy was false, but it’s still worth noting. Initially, the Bolsheviks actually promoted Ukrainian language and culture by creating a network of Ukrainian, rather than Russian, language schools. By the 1930s, of course, policies toward nationalities and minorities became very repressive under Stalin. However, in many ways policies promoting non-Russian national identities remained in place throughout Soviet history. So, Putin makes a claim here that the Bolsheviks with their nationalities policy actually created new nations.

Putin is using a much more nuanced scholarship in a brute force way. Recent scholars have argued that the Soviets created to some extent their own nationalities problem by sponsoring these different nationalities, which later split from the Soviet Union. And Putin is taking that point—he or somebody in his circle is aware of the scholarship—to an extreme, saying there was no Ukraine until the Bolsheviks created it by sponsoring Ukrainian culture. As we’ve seen, that’s a false claim.

Did Ukrainians welcome Nazi Germany’s invasion in 1941?

- In the far western parts of Ukraine—yes, but only at first. It quickly became clear that the Nazis were even worse than the Stalinists.

Lenoe: One of the stories you’ll hear is that when the German troops came, Ukrainian peasants were waving swastika flags, giving them bread and flowers. The Ukrainian peasants hated Soviet collectivization, so in the far west, Germans were probably welcomed. Although it’s not clear what happened in the rest of Ukraine, it quickly became clear that the Nazis were even worse than the Stalinists.

Ukrainians as a whole hated the Axis occupation. There was, however, a fairly widespread collaboration among Ukrainians in the Holocaust, based on long standing anti-Semitism. No question, there were police units that Ukrainians volunteered for which were involved in the mass murder of Jews. This is troubling now because both Poland and Ukraine, where there was extensive Nazi collaboration, have passed memory laws that aim to ban discussion of that collaboration—and Ukrainian nationalists really don’t want to talk about it.

Of course, it’s also true that there are about 2,500 Ukrainians who have been identified by Yad Vashem [the World Holocaust Remembrance Center] as belonging to “the righteous among the nations”—an honorary designation for non-Jews who aided Jews during the Holocaust.

What about Putin’s claim that Ukraine needs to be denazified today? Does Ukraine have a neo-Nazi problem?

- Putin’s claim of fighting for denazification in Ukraine distorts history. It’s another pretext to justify his invasion.

Lenoe: It’s a very complicated situation. The memory of the Holocaust and the far-right OUN, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists that was founded in 1928, is part of why Putin claims there are fascist or neo-Nazi elements in Ukraine. Indeed, it’s troublingly that in 2012 Stepan Bandera [an antisemitic Ukrainian ultranationalist leader involved in terrorist activities and a known Nazi collaborator] was officially named “Hero of Ukraine” by the government. Yet I should also note that there was a lot of liberal opposition to this in Ukraine. And yes, it’s true that there was and is a kind of a Ukrainian national/neo-Nazi movement that looks back, for example, to the SS in World War II as a positive memory. The election support for those people peaked in 2012 at about 10 percent; since then it’s dropped to below 5 percent.

In Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine now has a Jewish president who lost relatives in the Holocaust. So, yes, there is anti-Semitism in Ukraine, but it’s not overwhelming. And Putin’s claim that the Jewish Zelensky is a kind of neo-Nazi—well, we’re getting into some really preposterous territory here.

Do you think Putin believes his own statements on Ukraine’s history?

- Yes, says Lenoe.

Lenoe: I think that Putin believes what he has said. He was educated in this view of Ukraine when he grew up in the Soviet Union, and he puts this together with his understanding of the continued existence of NATO after the Soviet collapse, and US hegemony, and combines that with this idea that Ukraine is an integral part of Russia. And, he says, if Europeans are going to expand into Ukraine—whether as EU members or NATO—that’s basically NATO’s invading Russia.

He’s a desperate man: Russia’s international position before this invasion was weak, and now it’s far more so. Putin has created his own worst nightmare. If there was weak Ukrainian nationalism before, it will never be weak again. Ukraine will become like Poland, which you can take over, but never hold. He has inadvertently unified the West, along with countries like Japan and Korea, in an extraordinary bloc against Russia. Just to give you an example of how extraordinary this: the Germans have decided to increase their defense spending substantially. This was unthinkable before Ukraine’s invasion, partly because of Germany’s heritage of World War II.

How would you describe Putin’s decision to invade?

- It’s an irrational move driven by Putin’s perception of a threat to Russia.

Lenoe: This is the act of a desperate man who actually thinks there is an existential threat to Russia because of a possible NATO expansion. And it’s his hubris. It’s a sign that people aren’t necessarily rational, and that simple-minded versions of rational choice theory don’t work. This is a move that’s irrational on every level, that might even lead to Putin’s being overthrown by, for example, a military coup. In a sense, it’s his emotional attachment to these kinds of historical claims and also a sense that the collapse of the Soviet Union was a humiliation that must be avenged.