The first ensemble of its kind, the Eastman Wind Ensemble launched a movement in wind music.

Eastman Centennial

The Eastman School of Music is 100 years old. Learn more about our history and how we’re celebrating the century to come.

Ask an accomplished American wind musician when they first heard of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, and the responses are likely to be similar.

“High school,” says Jenna Kent ’20, ’20E, a master’s degree student at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and clarinetist in the ensemble. “Any time you go to look up a recording of a major piece of band rep,” says Kent, who grew up near Columbus, Ohio, “the first thing that comes up is an Eastman Wind Ensemble recording.”

“Probably late middle school,” says Luke Camarillo, a doctoral student in conducting at Eastman who played clarinet in his school band program in Corpus Christi, Texas. “Because almost any recording of major wind music that you might listen to in [a band program] was recorded, likely for the first time, by the Eastman Wind Ensemble.”

“I assume in high school,” says Jamal Rossi ’87E (DMA), the Joan and Martin Messinger Dean of the Eastman School, recalling the band program he participated in growing up in the Philadelphia suburbs.

Like Kent and Camarillo, Rossi, a saxophonist, traces his awareness of the ensemble to the moment he began to see himself as a serious wind musician.

The Eastman Wind Ensemble, founded at the Eastman School of Music in the early 1950s, is—and remains—legendary. “That’s not an overstatement,” says Rossi. “Through its commissions of new works and recordings, that are as robust today as at any point in its history, the Eastman Wind Ensemble continues to be the ‘gold standard’ among wind and percussion instrumentalists.”

That will be evident Friday night when, in a performance as part of the Eastman Centennial celebration, the wind ensemble premieres works by Tonia Ko ’10E, a Guggenheim fellowship winner whose compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, and other major venues; and Robert Paterson ’95E, whose accolades include the Classical Recording Foundation’s Composer of the Year. Both are testaments to the ability of wind ensembles in general, and the Eastman Wind Ensemble in particular, to interest dynamic and celebrated living composers.

Listen in on the latest

Hear samples from the Eastman Wind Ensemble’s most recent recording, Brightening Air (New Focus Recordings), with soprano Tony Arnold, performing music by David Liptak, professor and chair of composition at Eastman.

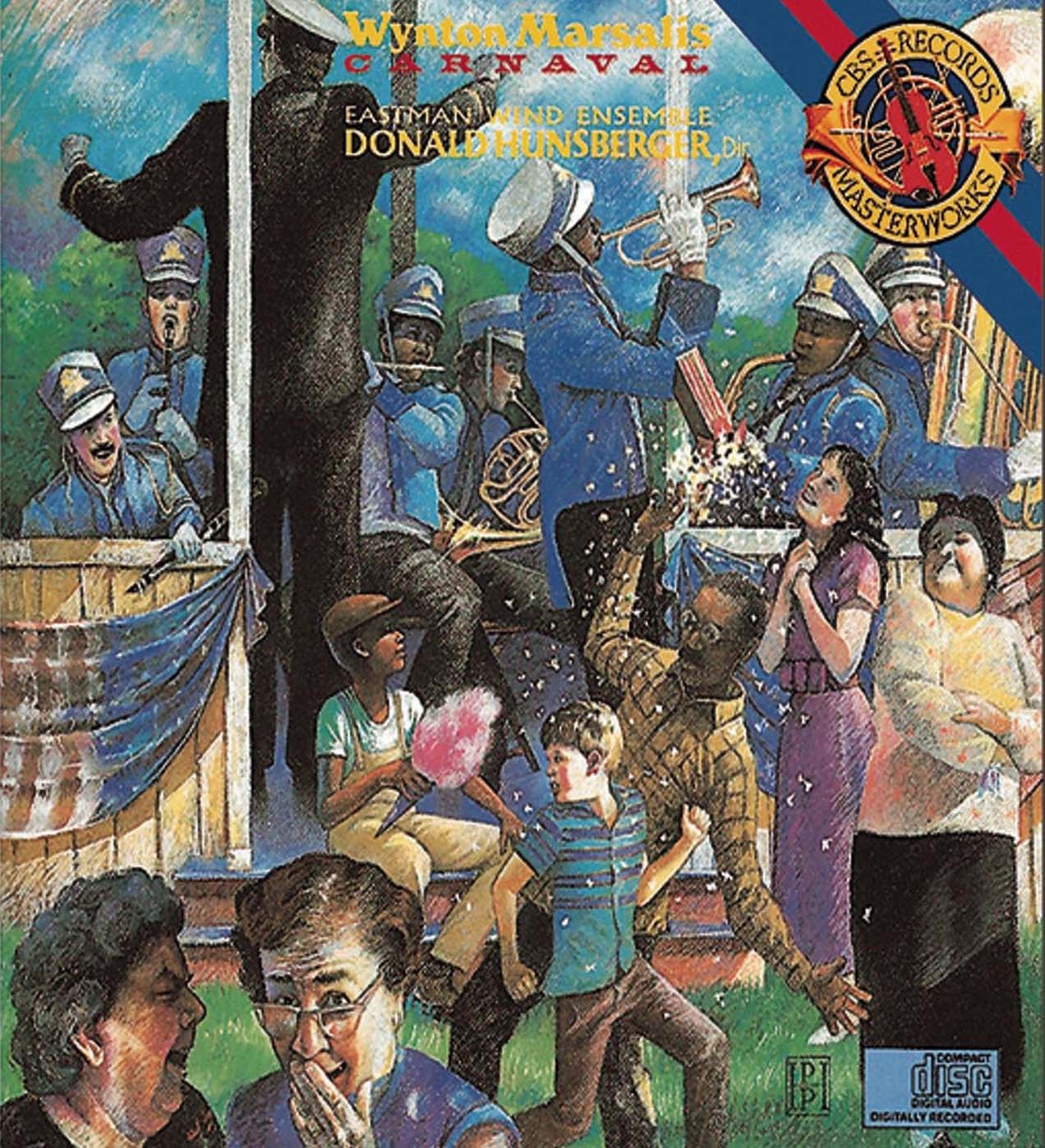

Mark Scatterday ’89E (DMA), who has been conductor of the ensemble since 2003, was a master’s degree student in trombone performance at the University of Michigan when he heard a recording that would change the course of his career: Carnaval, a collaboration of the Eastman Wind Ensemble and jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis.

“When I heard that recording, I knew I wanted to come here,” he says. “And I also knew that I wanted to be a wind ensemble conductor.”

Nearly 80 years after the founding of the ensemble, to conduct or perform with a wind ensemble is still to feel part of a movement.

The ‘wind ensemble concept’

When Frederick Fennell ’39E called the first rehearsal for the group in the fall of 1952, he was responding to a vexing problem for lovers of wind music. The golden age of the band—the era of John Philip Sousa—had come to an end. Bands were still widely popular among the public, and partly for that reason, directors relied on familiar music, much of it written for other instrumentation. Composers responded accordingly, with few writing for band.

A second problem was the neglect of a fine body of music written for winds, but not for the instrumentation of the modern band.

In what’s often referred to as his “manifesto”—Time and the Winds (1954)—Fennell wrote: “Music which does not fit the large instrumentation for the concert band or does not fall with ease into the carefully guarded categories of program routine which the band and orchestra maintain from the traditions established by the famous conductors, has no organized instrumental body which concerns itself with its performance. This music is, therefore, little known and seldom played.”

Fennell’s solution was an ensemble modeled on “flexible instrumentation.” The ensemble’s composition would change from piece to piece to reflect the music exactly as the composer scored it. If the composer scored the music for only three clarinets, it would not be performed with six or eight, as was customary in high school and college bands. There would be only one musician per part. With this instrumentation, “it is possible to perform, with but few exceptions, all of the great music written for wind instruments dating from the 16th century through the years to so recent and important a score as the Symphony in B flat (1951) by Paul Hindemith,” Fennell wrote.

The wind ensemble was also a means to build a robust repertoire of new wind music. In the summer of 1952, Fennell wrote to hundreds of composers announcing his formation of the new ensemble. He described it not as a rigid instrumentation, but as a musical resource from which composers could draw. To underscore that flexibility, the invention of the wind ensemble is sometimes called the invention of “the wind ensemble concept.”

Fennell’s invitations to composers bore fruit for decades to come. In the 1950s and 1960s, the ensemble produced 24 recordings on the Mercury Records label. Says Camarillo: “Any wind band, from high school to community or military bands, pretty much in the world, owes what it’s playing in front of them to Fred Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble.”

The ‘Eastman Wind Ensemble sound’

Fennell left the Eastman School in 1962 to become music director of the Minneapolis Symphony. The ensemble was led for two years by A. Clyde Roller, followed by Donald Hunsberger ’54E, ’59E (MM), ’63E (DMA), who in his 37-year tenure brought the ensemble to the international stage. Hunsberger joins the ensemble as a guest conductor this Friday.

“Don is my teacher and my mentor,” says Scatterday. “And he’s one of my best friends.”

Scatterday credits Hunsberger, who authored all of the arrangements for the ensemble during his tenure, with establishing an “Eastman Wind Ensemble sound.” That sound is warm and flowing, but it’s also a sound “that projects and has clarity.” And that combination can be challenging to achieve.

“It’s very easy to project a sound that’s not warm,” Scatterday says, referring to the bright, brassy sound that comes easily with volume. He’s made a point to continue to hone the sound Hunsberger envisioned. At a rehearsal, he reminds the musicians: “We can project, but we don’t have to be bright all the time to do it.”

Sound is so important in the ensemble, Scatterday says, that his approach to the start of a new piece, “Sound is first. The technique will come.”

Listen to a performance by the Eastman Wind Ensemble last October, as part of the Eastman Centennial celebration. Performances by the wind ensemble, many other Eastman student ensembles, as well as degree recitals, performances by faculty and guests, and more can be accessed on the Eastman School of Music YouTube channel.

A teaching innovation

Fennell also created the wind ensemble to address a pedagogical challenge. Elite schools of music such as Eastman were attracting top musicians whose training would be enriched, Fennell believed, with more opportunities to serve as soloists. Because there would be only one musician per part, every member of the ensemble essentially served in that capacity. Each musician had sole responsibility for an essential element of the piece. For wind musicians, no band setting offered that challenge.

To Jenna Kent, that makes playing in the wind ensemble “a lot of pressure, but also really rewarding.

“You know when you show up on the first day, it’s just you, and if you aren’t prepared to play your part, there’s no one there to help cover for you,” she says. That means that if you’re playing third clarinet, for example, “you’re the only third clarinet that there is.” And that’s what makes the experience of the wind ensemble special: “Every person is just so important.”

That aspect of the wind ensemble encapsulates Eastman’s philosophy of training musicians.

“The idea that every person has to be virtuosic in their own right, but also play together and blend and be an ensemble—that’s very much what we teach our students as a whole,” says Rossi. “As an artist, you have to have something unique to say. On the other hand, you have to blend and mesh together.” And as musicians prepare to go out into the world, “what they learn in wind ensemble helps propel them into that future.”

Learn More: Mark Scatterday’s Top Five

Whether you are just learning about wind music or want to revisit some classics, Eastman Wind Ensemble conductor Mark Scatterday offers you a place to start. Here are five Eastman Wind Ensemble recordings selected by Scatterday for their historical, artistic, and personal significance.

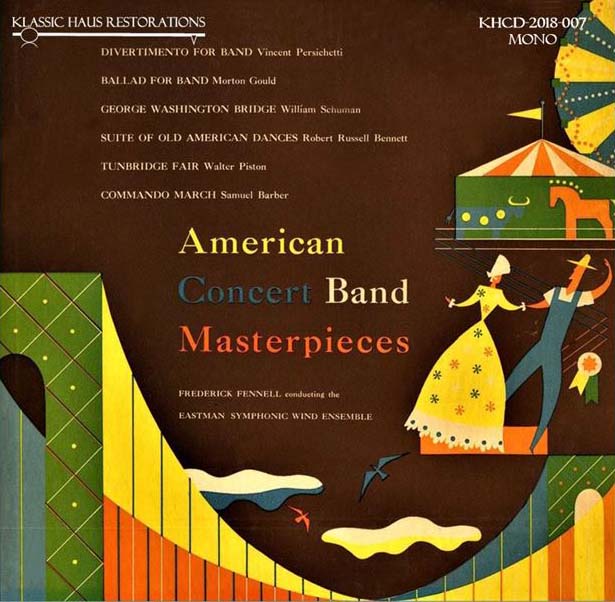

American Concert Band Masterpieces (Mercury/1953)

Frederick Fennell, conductor

As the very first recording by the very first wind ensemble, American Concert Band Masterpieces “set the stage and the bar for wind recordings,” says Scatterday.

As its title suggests, the album includes works written for “concert band.” These were among very few works written for band in the first half of the 20th century. In the coming years, Fennell and the Eastman Wind Ensemble would commission, premiere, and record many new works, leading to a robust repertoire for thousands of new wind ensembles formed on the Eastman model in the 1960s, 1970s, and later.

Carnaval, with Wynton Marsalis (CBS Masterworks/1986)

Donald Hunsberger, conductor

Carnaval is “probably the greatest recording ever made by the Eastman Wind Ensemble,” says Scatterday. Recorded in the Eastman Theatre over three days in September 1986, it showed “the finest in artistry, sound, and engineering,” he adds.

It also holds personal significance for Scatterday, who began his graduate education in music studying trombone performance. “When I heard that recording,” he says, “I knew I wanted to come [to Eastman]. And I also knew that I wanted to be a wind ensemble conductor.”

Carnaval enjoyed popular and critical acclaim. It was nominated for a Grammy Award in the category of Best Classical Performance: Instrumental Soloist with Orchestra, but competition that year was stiff. It was edged out by a recording of Itzhak Perlman performing Mozart’s Violin Concertos nos. 2 and 4 with the Vienna Philharmonic.

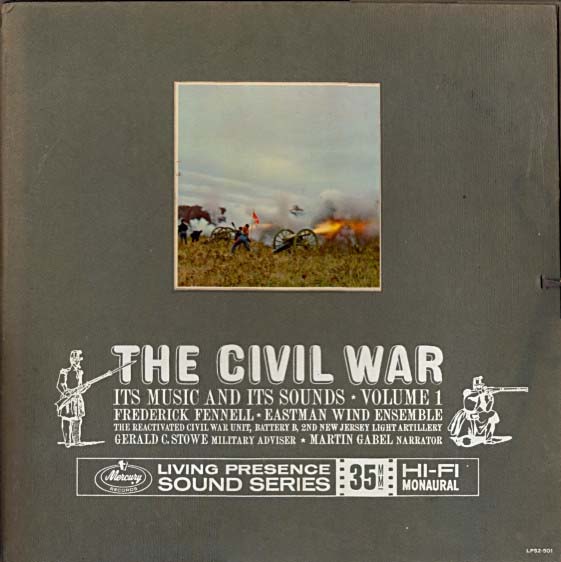

The Civil War: Its Music and Its Sounds (Mercury/1960)

Frederick Fennell, conductor

Scatterday calls this two-volume recording “historic,” adding that it was awarded a medal from the Congressional Committee for the Centennial of the Civil War.

Fennell sought to recreate a soundscape in which, as one contemporary recalled, military bands played polkas and waltzes while cannons exploded around them. The project involved deep research, with brass players performing on period instruments. Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns cited the recording as an inspiration for his epic, nine-episode documentary series The Civil War, and drew from it for the series soundtrack. Coinciding with the release of the documentary in 1990 was the release of a CD version of the Eastman Wind Ensemble recording.

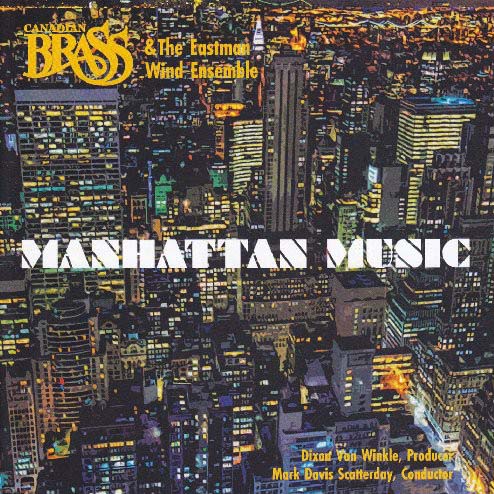

Manhattan Music with the Canadian Brass (Opening Day/2008)

Mark Scatterday, conductor

Scatterday calls this album, recorded in the Eastman Theatre in late September 2007, a collaboration of “two of the world’s finest wind groups,” and the project the source of “some of my best musical moments ever.”

Canadian Brass Quintet cofounder, tubist Charles Daellenbach ’66E, ’71E (PhD), was once part of the ensemble, and worked with Scatterday to create a repertoire, featured on the album, for a combination of brass quintet and wind ensemble. The album includes both new works and new arrangements, including an arrangement by Scatterday of Shaker Suite by Rayburn Wright ’43E (1922–1990), the longtime professor of jazz studies and contemporary media and cochair of the conducting and ensembles department at Eastman.

Manhattan Music was nominated for a Juno Award (offered by the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences and analogous to a Grammy).

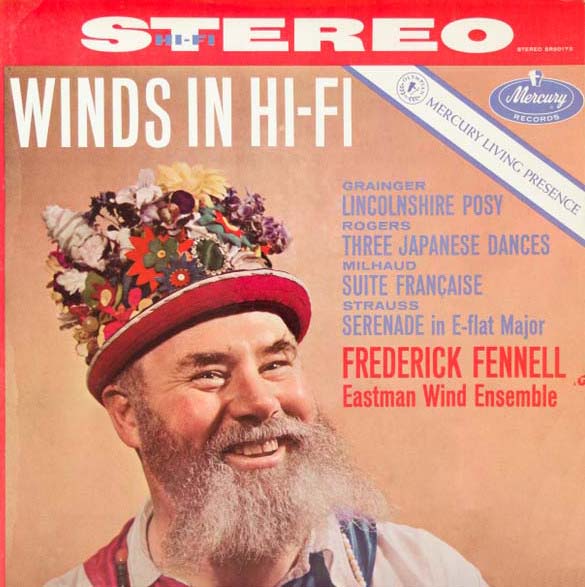

Winds in Hi-Fi (Mercury/1958)

Frederick Fennell, conductor

Scatterday recommends paying special attention to the first track, Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy. “It’s classic Fennell—probably his signature piece” as conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, Scatterday says.

In 1977, Stereo Review selected the 1958 LP as one of the Fifty Best Recordings of the Centenary of the Phonograph.