The professor emeritus’s research interests included Restoration biography, the Earl of Rochester, and 18th-century literature.

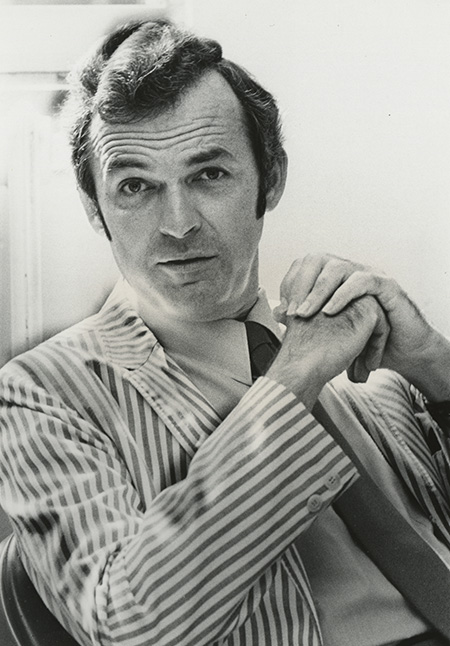

James William “Bill” Johnson, a professor emeritus in the University of Rochester’s Department of English, is being remembered by former students as a man with a passion for literature and life, a devoted teacher who was invested in his students in and out of the classroom.

Johnson was known professionally as J. W. Johnson during his time at the University, which spanned from 1955 to 1997. He died May 9, 2022, in Pasadena, California.

His research interests included Restoration biography, the relationships of the Earl of Rochester with the leading playwrights in London from 1660 to 1680, and his influence on later writers such as Swift and Pope. He was also interested in the works of contemporary writers such as Ionesco and Arrabal and the depiction of female and male models of conduct in motion pictures from 1920 to 1970.

Johnson was the author or editor of nine books, including A Profane Wit: The Life of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester; The Formation of English Neo-Classical Thought; and Logic and Rhetoric. He taught courses in subjects such as 18th-century literature, the English novel, women’s fiction, William Faulkner, women in film, and American male images.

“His seminars were dynamic and exhilarating,” says former student Sara Varhus ’74 (MA), ’80 (PhD), who earned her doctorate under Johnson’s supervision. “He was a ‘big picture’ thinker, always reaching for insights and synthesis. At the same time, he could quote from memory long passages and pithy statements by writers ranging from the ancient world to the present. Limericks, musical theatre, opera, Thornton Wilder—his interests were eclectic.”

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Johnson’s humorous anecdotes about his Southern heritage were a mainstay of his regular commentaries for public radio station WXXI in Rochester, New York.

From Birmingham to Rochester

Johnson was born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1927, the son of a clerk for a pipe company and a homemaker. When Johnson was born, one brother already was 20 and another was 15.

After high school, he enlisted in the Navy and served in Chicago and Corpus Christi, Texas, during the final stages of World War II. He recalled once receiving a request for volunteers to help conduct open-air tests of atomic weapons—before the lethal effects of radiation exposure were fully understood. He passed on the offer.

After being discharged in 1946, Johnson earned a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts at Birmingham-Southern College, then a master’s at Harvard University and, in 1954, his doctorate at Vanderbilt University. During his time in Nashville, he babysat future vice president Al Gore and had dinner with Minnie Pearl, the Grand Ole Opry comedienne.

Johnson spent the next year in London as a Fulbright Scholar. While there, he received a letter from Catherine Koehler, chair of Rochester’s English department, offering him a teaching position. As luck would have it, there was a Rochester associate professor in English named Maggie Denny who was spending a year in London. They met over lunch, and Johnson accepted the offer.

Johnson and wife Nan: ‘pillars of the University community’

At Rochester, Johnson met Nancy Heffelfinger, a graduate student at the University’s Warner School of Education, and the two married in 1957. “Nan” would forge a legacy of her own, serving at various times as a trustee of the State University of New York, an adjunct associate professor in Rochester’s Department of Political Science, and a 20-year run (elected six times) as part of the Monroe County Legislature starting in 1975. In 1995, she founded and was named director of the Susan B. Anthony Center at the University, a position she held until 1999.

“They were truly pillars of the University community,” says Richard Garth ’82 (MA). “Bill would do anything to help a student. One time I burned my hand in a cooking class. Bill knew a hand specialist at Strong Memorial Hospital and went out of his way to set up an appointment for me.”

Varhus said she became “an honorary family member” during her time at Rochester, often watching the Johnsons’ two kids or the family dog. But it wasn’t until she graduated that Varhus reached a new threshold in their relationship. “When I and a few other English graduate students received our degrees at the 1980 commencement, he stepped forward to hand us our diplomas and announced, ‘Now you can call me Bill!’’’ she says.

Varhus says Johnson projected a sophisticated image on campus that contrasted with the trend of the times.

“In the late 1960s and early 70s, when most of the graduate students and many of the faculty embraced a somewhat scruffy look, Bill stood out as an elegant figure—tall, with a mane of wavy hair, wearing ascots and suits,” she says. “He also demanded that his seminars be smoke-free. He was ahead of the times.”

She adds that, “like the great satirists of the 18th century, Bill had a deep appreciation for the human comedy. Whether directed at literary characters or people in the evening news, his commentary was ironic and witty. And his Alabama accent made his pithy statements all the more incisive.”

Johnson and his wife often entertained his graduate students in their elegant home on Oliver Street. “I recall lively evenings with wide-ranging talk and laughter,” Varhus says.

‘He was the reason I made it through’

Annette Forker Weld ’89 (PhD) remembers Johnson as “kind and quick-witted.” She says she was a “non-traditional student”—a mother of three and pregnant with her fourth. “Bill understood that my academic journey was dependent upon babysitters, rare quiet time alone for reading and writing, and a sympathetic husband who carried more than his share of the parenting load,” Weld says. “At the time, Bill read the names of the graduate students at commencement, draping us in our academic hoods. He gave me a hug along with the hood, and afterward, my family enjoyed champagne with Nan and him at their home. He was the reason I made it through.”

Robert Miola ’77 (PhD) says Johnson was “witty, provocative, and dazzling in his command of the material and his ability to excite interest, ask probing questions, or go on wonderful tangents. He was superb.”

Johnson retired from teaching in 1997 and spent 20 years living with Nan on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, with travels to Tierra del Fuego, West Africa, Southeast Asia, Russia, Australia, and the Pacific Islands sprinkled in. The two moved to Pasadena in 2017 to be closer to their children and grandchildren.

In addition to Nan, Johnson is survived by his daughter Miranda, and her husband, Mark Haddad, of Pasadena; son Reed and his wife, Marla Dickerson, of Los Angeles; and grandchildren William Haddad; Elinor Haddad and her husband, Cris Swain; and Annabel Haddad.