A Rochester research team is part of an inter-institutional study on one of film and television’s most powerful techniques.

There are people who haven’t dared to watch Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 horror film The Shining; yet they’re familiar with the chilling image of a crazed Jack Nicholson pushing his face between the panels of an axe-broken door. That visual is an iconic example of one of the most powerful techniques in film and television: the close-up.

Through a $100,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation’s Public Knowledge Program, the close-up is the subject of a 15-month collaborative study between the University of Rochester and Bowdoin College. The project, “A Digital History of the Close-Up in Narrative Film and Television,” is being led at Rochester by Joel Burges, an associate professor of English and of visual and cultural studies. His partners at Bowdoin are Allison Cooper, an associate professor of romance languages and literatures and cinema studies, and Fernando Nascimento, an assistant professor of digital and computational studies.

Hollywood would be hard-pressed to script a better partnership.

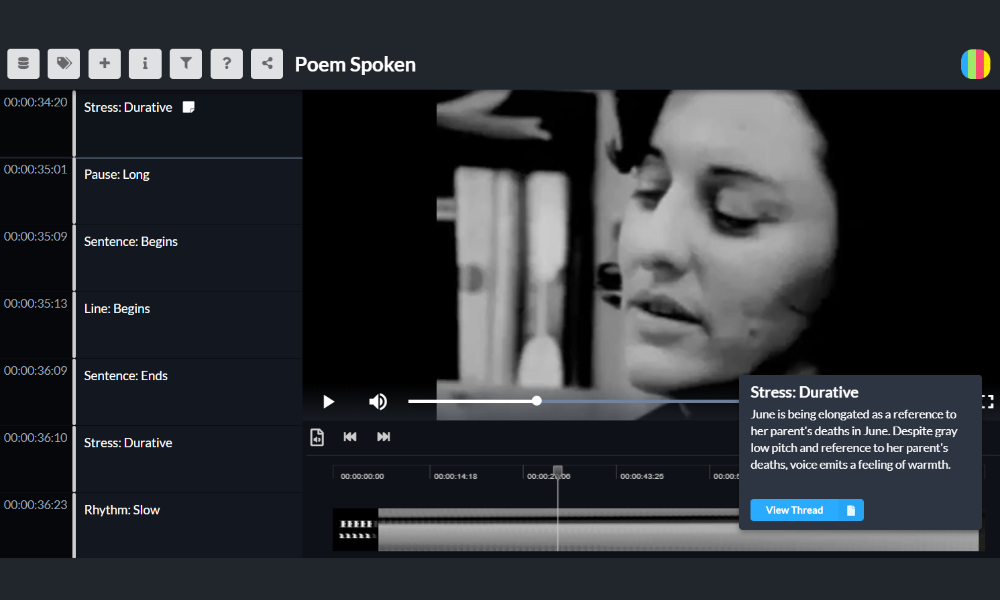

Burges, who also teaches courses in film and media studies and digital media studies, is the principal investigator on Mediate, a digital annotation tool for audiovisual and time-based media. And Cooper is the director of Kinolab, a public-facing, searchable, open-access database of annotated film and television clips.

“Although Kinolab and Mediate have different orientations, they are highly complementary,” Burges says. “In fact, we hope to eventually make them interoperable. So, clips annotated in Mediate can be directly exported into Kinolab, potentially with visualizations of the data gathered about film and television that would allow users of both platforms to observe patterns in storytelling, sound design, and visual decisions.”

At Rochester, the study will have support from undergraduate researchers and several River Campus Libraries staff members:

- Emily Sherwood, director of digital scholarship and of the Mary Ann Mavrinac Studio X, for exploratory data analysis and work with student curators

- Vinicius Romualdo, digital scholarship designer, for user experience support

- Jeff Suszczynski, digital scholarship developer, for platform support and the sharing of data and data models between Mediate and Kinolab with help from Romualdo

- Maggie Dull, director of metadata strategies and interim director of digital initiatives, to guide decisions on the metadata categories central to the grant’s research questions

Working together, the inter-institutional team will curate, analyze, and interpret an at-scale collection of moving image examples of the close-up in narrative film and television.

What are close-ups, and why study them?

A “close-up” is any camera shot in which a character’s face, an object, or scene detail takes up most or all of the frame.

“Of all the different kinds of shots that go into telling stories using film, the close-up is probably the one we most take for granted and don’t notice,” Cooper says. “But it’s actually very important to the way films communicate meaning. And because it is so powerful in directing the viewer toward a particular aspect of the story, it seemed like an obvious aspect of film language to think about more closely.”

Close-ups started appearing in silent-era films in the early 1900s. At the time, it was an innovative technique as it was standard for a filmmaker to set up the camera and let it roll. While many were reluctant to use the close-up, there were early adopters like Russian and Soviet filmmaker Vsevolod Pudovkin, who wrote in his 1933 book Film Technique and Film Acting that his peers primarily saw the close-up as an “interruption of the long-shot.”

“Nobody had thought, ‘Oh, we could change the way the audience understands the story if we cut the film here and insert a shot of something else,’” says Cooper.

Long gone are the days of close-up skeptics. Data collected by Kinolab has shown that “close-up” is associated with film clips more frequently than any other film language tag.

Despite being a staple in on-screen storytelling for the past 100 years, the close-up remains an under-examined part of cinema. Does the average filmgoer or television viewer consider how close-ups shape our perceptions? If they do, Burges and Cooper suggest they do it intuitively rather than analytically. While some important scholarship has begun to emerge, there is no at-scale understanding of how the technique puts different aspects of race, gender, sexuality, or class into the foreground, over time, or across film styles. Nor has much attention been paid to its use in television through genres such as drama and comedy, at specific networks, or by directors who work in film and television.

Their research aims to lay bare the hidden history of the close-up and how it intersects with the representation of race, class, gender, and sexuality on screen.

Generating the data

The study will be conducted in five phases, beginning with the curation of films and television episodes to develop an expanded, public-facing dataset, focusing on works created by and featuring American BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) and LGBTQI+ directors, showrunners, and performers.

“When you start to think about the uses of the close-up,” Burges says, “it’s not just about looking at whether or not a Black actor, Indigenous character, or queer performer gets their close-up, though that question is essential to us. It’s also about looking at who’s behind the screen making and influencing shot decisions in the collaborative and hierarchical processes that go into the production of film and television.”

But first, data has to be generated.

Cooper, Burges, and Sherwood have assembled a team of undergraduate student curators from Rochester and Bowdoin. Using Mediate, they will annotate existing and newly collected film and television clips with metadata, enabling them to be discoverable in Kinolab—in essence, marking every close-up and creating tags critical to making clips findable.

“It’s exciting that Mediate—this platform that we’ve been working on for a decade—is being used to do this analysis in partnership with another institution,” says Sherwood, who has been a crucial collaborator with Burges on Mediate. “This is also a great opportunity for us to continue to enhance the platform’s user experience and start exploring the best way for it to work with other platforms, like Kinolab, which this project requires.”

As the heavy lifting of annotating and marking clips occurs, researchers can begin to ask questions. For example, are Black Americans doubly marginalized in science fiction films? Historically, these films have been made predominantly by white filmmakers, featuring white performers, and relegating Black actors to supporting roles, precluding them from close-ups. Hypotheses like this one are important to realizing one of the study’s most important goals: new exemptions to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Copyright and fair use for audiovisual materials

The DMCA protects copyright holders and their intellectual property from unauthorized production or dissemination. However, it also outlines what constitutes fair use—such as including a movie still in a film and media studies textbook.

While existing exemptions enable research and support teaching, Burges and his collaborators aim to use the documentation of their work as a use case that shows how the DMCA needs to be amended to account for the changing conditions under which film and media studies scholars do their work. The team will supplement this assertion with recommendations for expansions that would further empower researchers to conduct large-scale data analysis of film and television and facilitate many levels of education.

Every three years, the Library of Congress reassesses what constitutes fair use under the DMCA, which last occurred in 2021. In 2024, Burges and Cooper will make their findings more broadly available through peer-reviewed scholarly work, academic conferences, and short films and videographic essays.

“We want to ensure film and media studies scholars—and scholars in general—can access these materials,” says Burges, “And that they can show them in classrooms and do research around them, without having to confront the full weight of corporations coming down on them, saying ‘No, no, no. You can’t use this clip.’”

About The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is the nation’s largest supporter of the arts and humanities. Since 1969, the Foundation has been guided by its core belief that the humanities and arts are essential to human understanding. The Foundation believes that the arts and humanities are where we express our complex humanity, and that everyone deserves the beauty, transcendence, and freedom that can be found there. Through our grants, we seek to build just communities enriched by meaning and empowered by critical thinking, where ideas and imagination can thrive. Learn more at mellon.org.

Read more

Horror films offer a psychological thrill ride

Horror films offer a psychological thrill ride

Jason Middleton, director of the Film and Media Studies Program and a student of horror films, talks about the paradox of horror—why people seek to be scared as entertainment.

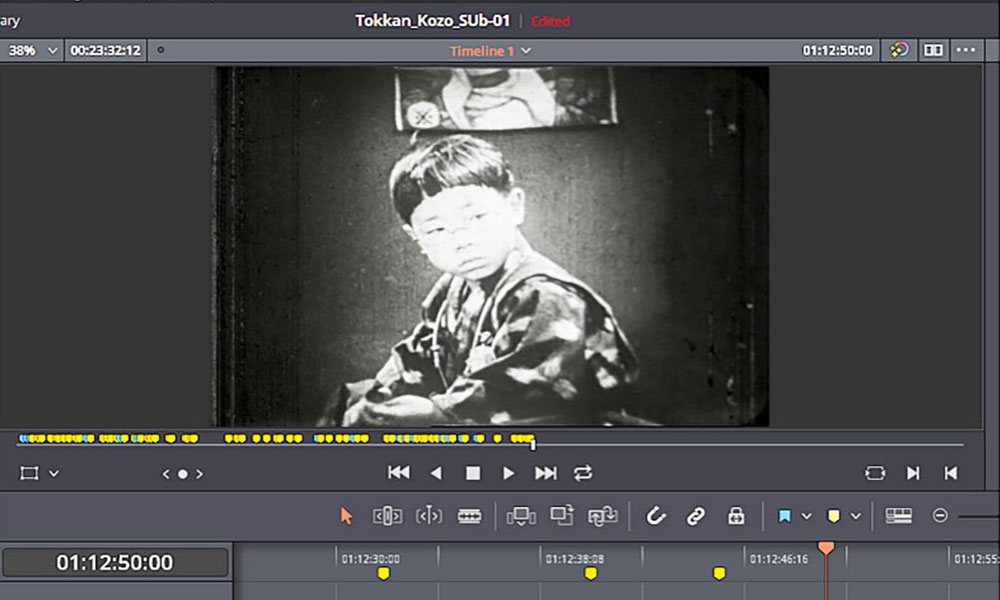

Digital scholars rescue lost Japanese film

Digital scholars rescue lost Japanese film

A 1929 Japanese silent film inspired by a classic O. Henry short story was thought long lost until Rochester researchers collaborated to bring it back to the big screen.

Digital justice through data dictionaries

Digital justice through data dictionaries

A seed grant from the American Council of Learned Societies launches a project that has the River Campus Libraries helping to diversify the digital domain.