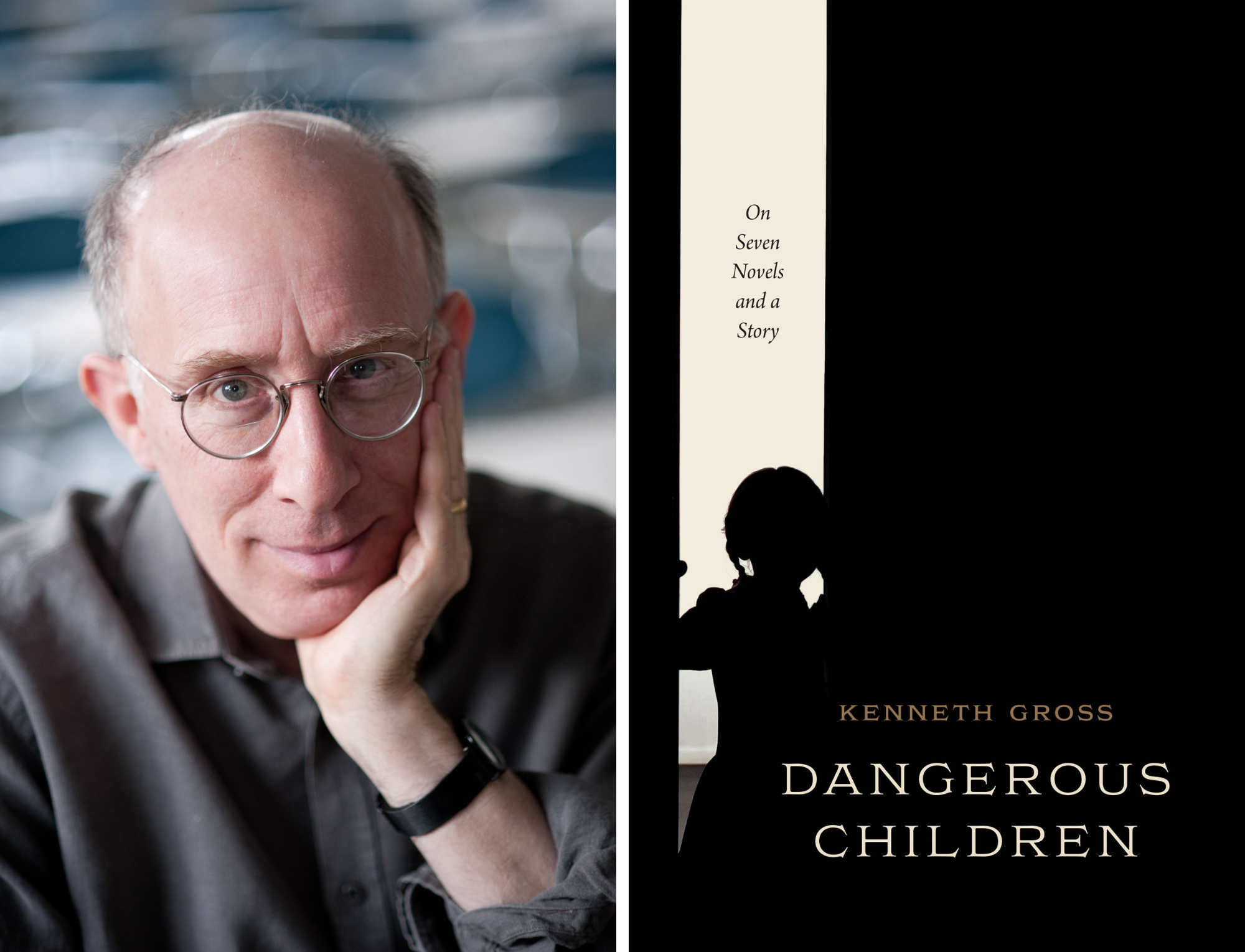

Teaching an undergraduate class on ‘dangerous’ children in literature inspired English professor Kenneth Gross’s latest book.

“… a student once wrote to me …” “… a student once reminded me …” “… a student once said to me …” “… one of my students felt …”

Kenneth Gross’s latest book routinely acknowledges the insights and contributions of his University of Rochester students. That’s because Dangerous Children: On Seven Novels and a Story (University of Chicago Press, 2022) was inspired by his teaching of an undergraduate class “in a more fundamental way than anything else I’ve ever written,” he says.

The book takes the title of the 200-level course that Gross, the Alan F. Hilfiker Distinguished Professor in English, has taught three times, most recently in spring 2022. Students read and analyze texts in which the authors imagine childhood, especially stories centering on the figure of a dangerous, strange, or uncanny child. “What is dangerous in them is no one thing, and keeps on changing,” he writes in the prologue. It often lies simply in how adults see them as dangerous.

The class includes works spanning nearly a century, starting with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, published in 1865, and ending with Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, which came out in 1955. The book follows this outline, with Gross dedicating a chapter to each of eight works that have regularly appeared on the syllabus: Carroll’s Alice, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, Henry James’s What Maisie Knew, J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy, Franz Kafka’s “The Cares of a Family Man,” Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica, Elizabeth Bowen’s The Death of the Heart, and Nabokov’s Lolita.

Three of the selected children (Alice, Pinocchio, and Peter) belong to stories written with child readers in mind—though they’ve always drawn passionate adult audiences—and the other five come from works written for adults. And notably, each child’s fictive career ends before they can ever come of age on the page.

Through teaching the class and writing the book, “I was inventing for myself ways of bridging the gap between books for children and books for both children and adults,” says Gross. “But I also tried to find a language that would bridge audiences of scholars, students, and general readers.”

The paradox of the uncanny child

Written in an open, essayistic, narrative style and incorporating the author’s digressions, obsessions, personal anecdotes, and even fictions, Dangerous Children aims to capture some of the energy of the classroom. His students, Gross recalls, “had such wonderfully surprising and idiosyncratic responses to the books.”

What intrigued—and sometimes shocked—them was how these literary children could upend their own long-held assumptions. “They expected the children to be innocent, cute, or adorable. Or they were familiar with gothic or sci-fi children who are evil, demonic, or monstrous. But it was that playful or uncanny middle space between the innocent and the demonic that really fascinated them,” he says. Particularly when that playful middle space clashed with the students’ own childhood memories of or experiences with the texts.

“They would be astonished to discover, for example, that Pinocchio was so much weirder and more desperate, more violent and also more vulnerable, than they’d been taught by Disney,” Gross says. Indeed, he adds, “One student who had searched out the original text of Pinocchio online thought at first that she was reading a piece of fan fiction.” (Spoiler alert: In Collodi’s story, Pinocchio kills the cricket, among other instances of violence. And while Gross avoids spoilers in class, he warns readers that the book is necessarily replete with them.)

In Gross’s account, fictional children can become ideal carriers or occasions for experiencing the Freudian notion of the “uncanny,” that feeling of strangeness that is nonetheless rooted in familiarity, in ordinary things—a notion central to Gross’s 2011 book, Puppet: An Essay on an Uncanny Life (University of Chicago Press). Dangerous Children gave him a chance to expand his thinking by exploring the different shapes the uncanny can take with child figures: from playful to nonsensical, feral to haunting, secretive to exposed. “These fictional children ended up teaching me about myself, my own unconscious, and my own mind and obsessions—they point to forms of thought and play that remain part of one’s life as an adult,” he says.

So, will Gross offer the course again? Or is it time for him, as is said, to “put away childish things?”

“If I teach it again, I’d want to change many of the texts.”

In addition to numerous examples from mythology, fairy tales, and poetry, he cites the writings of contemporary authors like Maurice Sendak, Shirley Jackson, and Toni Morrison. “There are lots of other strange children out there for the students to read and think about. The one thing I know is that I’d still have to start with Alice. The landscape of Wonderland is the best place to begin.”

Read more

Teaching the complexities of the Nobel Prize in Literature

Teaching the complexities of the Nobel Prize in Literature

English professor Bette London introduces students to Nobel-winning authors and the controversies surrounding the prize.

English major from The Gambia helps preserve ancient African fables

English major from The Gambia helps preserve ancient African fables

Fatoumatta Jobe is transcribing in Wolof—and then translating into English—centuries-old stories passed down orally.

Questions of character and motives drive professor’s new novel

Questions of character and motives drive professor’s new novel

In Stephen Schottenfeld’s This Room Is Made of Noise, a down-on-his-luck handyman befriends an elderly widow of means. What’s a reader to think?