In Rochester’s International Theatre Program, intimacy directing is playing a growing role.

On-stage intimacy work has become a pillar of the theater industry, and it’s becoming a more integral part of performances by the International Theatre Program at the University of Rochester.

Leading the program’s effort is Sara Penner, a senior lecturer of theatre in the Department of English and a voice and acting coach for the International Theatre Program. She compares the work of an intimacy director to the role of a fight director.

“Any time you do a fight on stage, you have a skilled fight director on a set, so actors can be safe doing the work and not hurt each other,” she says. A fight director makes a safe space by carefully choreographing scenes. Intimacy directors help honor actors’ needs for bodily autonomy and boundaries by taking a similar approach.

The field of intimacy direction, coordination, or choreography began informally, about 10 to 15 years ago. Its growth accelerated along with the #MeToo movement, and training programs started to appear, as well as an accrediting agency. Access to theatrical intimacy training, through virtual workshops, grew nationwide during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Penner, it’s not necessary to be certified as an intimacy coordinator or intimacy director, but you do need certain skills. “You need to have a movement background that gives you the skills and language to explain movement in a desexualized way,” she says.

Penner’s interest in intimacy directing grew out of her work on a 2019 production for JCC CenterStage called Indecent. While playing Manke/Freida, she worked for the first time with an intimacy director. Says Penner, “I thought, ‘Why wasn’t this the way we have always worked?’”

From that experience, Penner went on to shape consent policies and practices for the International Theater Program. She was awarded a Teaching Innovation Grant in 2022 to support her work building new courses and practices. Penner also began teaching a consent and performance course through the Institute for Music Leadership at the Eastman School of Music.

While the International Theatre Program is no stranger to intimacy work in its repertoire, the spring 2023 production of Mary Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses offered a suitable opportunity to introduce an intimacy director. A contemporary retelling of the ancient poem by Ovid, the play contains abstract sexual scenes, as well as depictions of drowning, incest, and simulated violence. “There needs to be a clear chain of communication for the students,” says Penner.

Brittany Broadus ’24, one of the performers in Metamorphoses, is grateful for Penner’s intimacy direction. Recalling a difficult role she played in a high school theater production, Broadus says she wishes she could have advocated for herself more and is now realizing things could have gone differently. She describes the experience of working with Penner as “being taught that it’s okay to talk about my boundaries as a person and knowing that there would be no repercussions for that.”

How does intimacy direction work?

Intimacy coordination or direction makes intimacy work collaborative. With Penner, the students work on partner-building exercises during what’s called a consent-based rehearsal. The exercises are designed to support the actors’ ability to do mentally, emotionally, and physically challenging work. During rehearsals, the actors form a circle and call out to each other, one at a time, “May I touch your arm?” The facing actor may say “yes” or “no.”

“The students are learning to ask before they touch,” says Penner. The physical boundary practices also give the students the space and tools to communicate their boundaries in the rehearsal process.

“When we look at choreographing these intensely intimate moments, I use Intimacy Directors and Coordinators Five C’s: context, communication, consent, choreography, and closure,” Penner says. The process always begins with collective agreements: What do you need to be able to work in a safe space? What do you need from a partner, and what do you need to bring yourself? “Then, we work with those physical boundaries, which don’t need to be justified, as specifically as possible,” she says.

Actors are also provided an exit strategy. “I spend a lot of time helping them understand ‘where is comfortable?’ and how we can stretch ourselves, but not push over into pain or trauma,” says Penner.

In Metamorphoses, the significant moments of intimacy are built one step at a time through choreography and desexualized language. The process is “very technical,” according to Penner. “It’s determining exactly where a hand goes, counting how long a kiss lasts for, the duration of each activity.” As an intimacy director on Metamorphoses, she collaborates with director, Joe Calarco, to decide what story they are trying to tell physically and contextually and if there’s another way to do a scene. “A kiss might become a gesture, an embrace or a long stare into each other’s eyes,” says Penner. In a film or on stage, the director may use imagery or non-literal storytelling, and the audience may interpret that visual however they want.

“There are a million ways to tell a story,” she says.

Intimacy and consent in the classroom and beyond

Intimacy coordination and direction has started expanding beyond the International Theatre Program.

Lindsay Baker, an adjunct opera instructor and acting coach in the Voice, Opera, and Vocal Coaching Department at the Eastman School, has also advocated for intimacy work in recent Eastman Opera Theatre productions while incorporating consent-forward practices in the classroom.

“Beyond intimacy, I’m thinking about how we create a classroom setting, or spaces, where there’s open, transparent communication—where we honor accessibility and access needs,” says Baker, who choreographed intimacy for the Eastman Opera Theatre’s spring opera Florencia en el Amazonas and is currently providing intimacy direction for the Penfield Players community theater group. Those types of spaces, she adds, are where educators “help [students] do their best learning.”

One of Baker’s students, Isaac Pendley ’23E (MM), played the role of Alvaro in Florencia. Although he had heard of intimacy coordination, he’d never experienced intimacy choreography firsthand before coming to Eastman. Singing-actors like Pendley face special challenges: in addition to the blocking and live acting required on stage, they also have to perform intense and demanding vocal techniques. But intimacy coaching before and during rehearsals can help ease that cognitive burden. “It provides a firm foundation for the scenes to be built on, freeing up the performer to focus on bringing the character to life and singing well,” he says.

Meanwhile, Penner—who this past year served as the intimacy director for the National Technical Institute for the Deaf’s production of Deaf Republic, The Company Theatre’s The Seagull, and the International Theatre Program’s The Crucible and The African Company Presents Richard the Third—is expanding her work beyond performance spaces, into clinical settings. She’s collaborating on an article for the Journal of Child and Maternal Health with Dr. Caitlin Dreisbach, an assistant professor at the School of Nursing and in the Goergen Institute for Data Science, and Dr. Nicholas Mercado, an assistant professor in the Department of Health Humanities and Bioethics. The team is looking at incorporating consent more effectively for nurses in birthing spaces.

“The world is rapidly changing in the way we meet people where they are; we can teach people practical tools so they can make a difference in their job,” says Penner. “If more people know this work is happening, more colleges and universities will make the space for it to happen.”

Read more

Can arts integration deepen students’ understanding?

Can arts integration deepen students’ understanding?

A partnership between City of Rochester schools and the Memorial Art Gallery leads to innovation in arts education and furthers the museum’s mission to serve the Greater Rochester community.

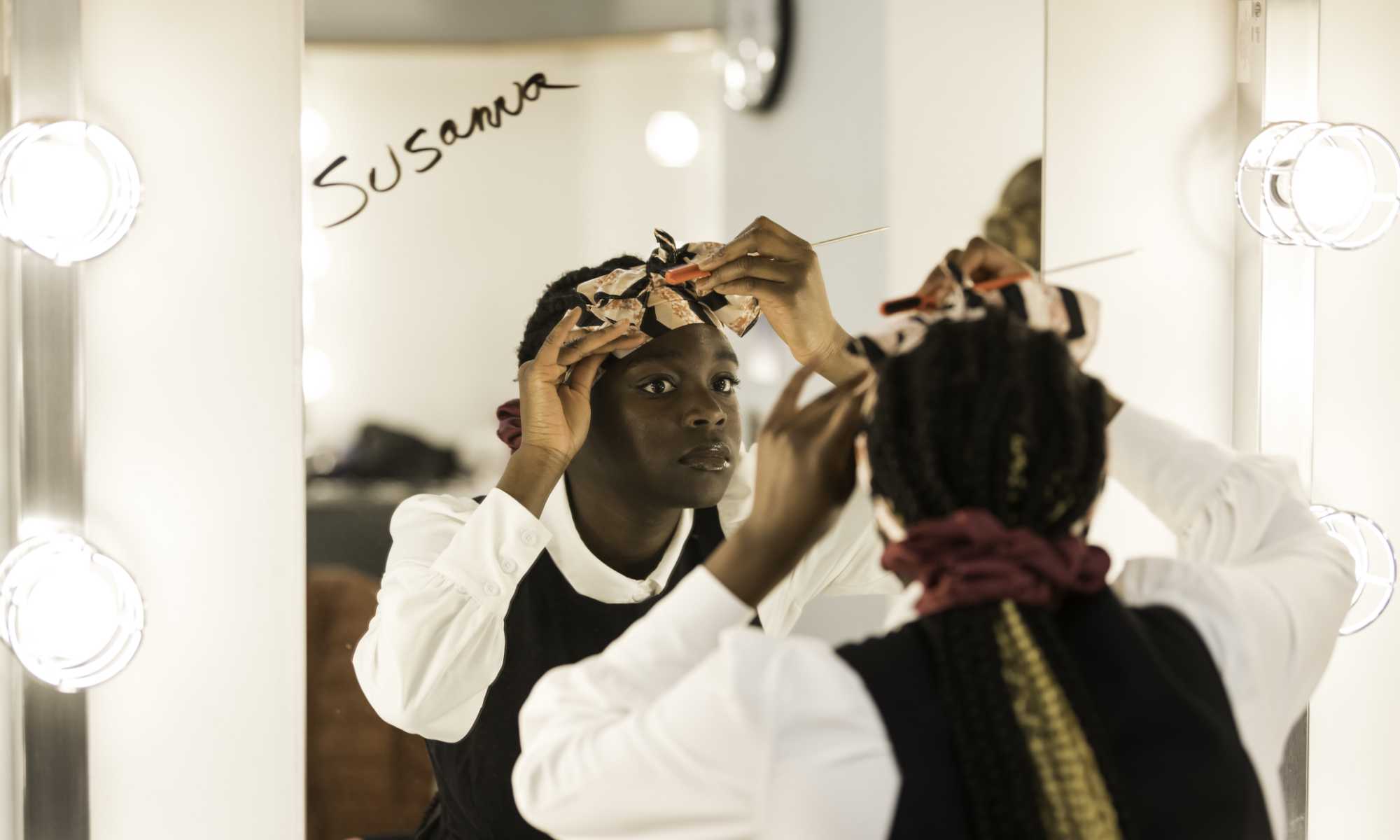

Changing the narrative about Blackness on the stage

Changing the narrative about Blackness on the stage

By partnering with Black actors and artists, the International Theatre Program’s recent productions help give new dimension to marginalized characters.

Using improv to address COVID vaccine hesitancy

Using improv to address COVID vaccine hesitancy

A new program combines improv theater techniques with coaching on motivation theory to help health care workers guide patients during conversations about vaccination.