A Rochester economist applies lessons from the 1980s to explain the United States’ current trade war with the potential superpower.

United States tariffs on China increased in 2018 during the Trump administration, prompting a trade war with the economic powerhouse. Since coming to office in 2020, President Biden has maintained those tariffs. Nonetheless, expectations of a prolonged trade war were low during the Trump years, yet have remained high during Biden’s term in office.

What accounts for this discrepancy?

To answer this question, University of Rochester economist George Alessandria and his coauthors analyzed historical data to construct an economic model predicting the probabilities of a prolonged trade war. That model takes into account parallels with the US-China trade war during the presidential tenures of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, from 1977 to 1981, and 1981 to 1989, respectively.

The conclusions, which Alessandria calls counterintuitive, are discussed in a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper titled “Trade War and Peace: US-China Trade and Tariff Risk from 2015–2050.”

Alessandria, an expert on international trade, attributes the differing probabilities of a prolonged trade war to the changing expectations of individuals and firms.

Q&A about the trade relations between US and China

What is a trade war in economics?

- A trade war occurs when two countries impose higher tariffs or taxes on imported goods or services from each other, which increases the cost of those goods or services, and shifts purchases away from these goods to other sources.

Alessandria: There’s no technical definition of the term trade war. It’s like obscenity; you know it when you see it. Essentially, a trade war exists when one country tries to get another country to pay more for its goods. That’s done by imposing tariffs (essentially taxes) on imports. For a true trade war to exist, both countries need to be imposing higher tariffs.

Probably the best-known trade war happened during the Great Depression. In June 1930, the United States raised import tariffs through the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. The aim was to protect American businesses and farmers, but then the rest of the world ended up raising their import tariffs. The net effect was a reduction in global trade and an even worse world economy.

How do trade wars typically affect the US and global economies?

- Trade wars raise the price of imported goods and lead consumers and firms to substitute for those higher-priced products. That substitution builds more or less through time depending on how long people expect a trade war to last.

Alessandria: At the most basic level, trade wars raise the cost of buying a set of goods from certain trade partners. This leads firms, and ultimately consumers, to buy less of these products. They shift to other sources, which could be other trade partners or domestic producers. Trade then falls, particularly on the most affected products. Trade wars work in the opposite way of trade peace and free trade agreements, such as the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement, an updated version of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA. These agreements open markets by reducing or eliminating tariffs on select goods moving in either direction.

The effect on the aggregate economy of a trade war is harder to sort out. Economists have found that raising tariffs will in general lower economic activity, lower real income, and reduce jobs. However, in the short-run you might get a boost in economic activity since you might have to hire more workers to adjust production lines and supply chains. Those investments are needed to offset some of the higher costs of doing business.

What happened after the Trump Administration imposed tariffs and COVID-related exclusions on thousands of Chinese imports in 2018 and 2019?

- As expected, the United States reduced its purchases of the goods with increased tariffs. But, importantly, the initial shift away was relatively small because the tariffs weren’t viewed as likely to last for very long.

Alessandria: No one really thought Trump was going to raise the tariffs; they thought he was just posturing. But once Trump raised the tariffs, everyone—economists, policymakers, pundits, firms, the general public—assumed he was just trying to get a deal, or that the tariffs would go away when he left office. In other words, people figured, “Sure, Trump raised tariffs, but it’s likely only for a year or two.”

In the meantime, in true trade war fashion, China raised its tariffs on US exports. They also lowered tariffs on exports from other, non-US sources to shift trade away further from the United States while mitigating some of the effects on their consumers and producers.

Why did the US-China trade war accelerate under President Biden, even though he didn’t raise tariffs?

- By not reducing tariffs, President Biden and the Democrats indicated to consumers and firms that tariffs would remain higher longer than expected—subverting their expectations.

Alessandria: When Biden didn’t reduce tariffs—which he could have done on day one of taking office, but didn’t—people’s expectations changed. As a result, Biden and the Democrats were perceived as being more anti-trade than originally thought. People and firms realized that the trade war between the US and China was a big deal after all—and that tariffs would likely remain high a lot longer than expected.

I’ll give you an analogy. Suppose there’s going to be a tax holiday during which sales taxes are temporarily reduced or eliminated. Knowing that information, fewer people would buy dishwashers in advance. But once the tax holiday comes, many more people will buy dishwashers. A rational person would wait for the tax holiday in order to save money. Economic decisions—by individuals, by firms, and by nations—are based on a combination of information about what’s happening today and expectations of what will happen in the future.

What lessons from the Carter and Reagan administrations helped you understand today’s trade war?

- There are parallels between the trade reform of 1980 and the increased tariffs of 2018, with the responses to both being similar in magnitude and trajectory. But the big takeaway is that expectations about a leader’s trade policy position can have an outsized impact on trade relations between countries.

Alessandria: In terms of trade flows, we see parallels between the decrease in tariffs in 1980 and the increase in tariffs in 2018. The trade responses before and after these two reforms are similar in magnitude, but in the opposite directions. The 1980 reform took a while for people to believe it would last, and so trade grew slowly and only really picked up in Reagan’s second term. Trade then really grew a lot. We’re at a similar stage right now. We’re buying less from China, but we haven’t cut back as strongly as we could.

The other thing we learned is that trade policy reflects wider geopolitical concerns. It was a complicated relationship between the US and China going back to 1949 with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. The US had backed the Nationalists, under Chiang Kai-shek, over the Communist forces, which eventually won. Soon after, we were on opposite sides of the Korean war. The result was a long period of hostile relations between the two countries.

Years later, ping-pong diplomacy—the exchange of table tennis players between the US and China in 1971—paved the way for Nixon to visit China the following year, which began the return to normal trade relations.

Then at the end of 1978, when China got a new government under Deng Xiaoping, then-President Carter decided to recognize China, which meant establishing official diplomatic relations. But the thawing of relations with China went against the more conservative wing of the Republican party, which Reagan saw as an opportunity to strongly position himself as anti-communist.

When the tariffs fell under Carter in 1980, people started buying more Chinese goods. Once people start buying more stuff, firms typically start trying to find more customers and making investments to tailor products to consumers in those export markets. And that second round of growth comes because firms think that the tariffs are going to be low in the future. After Reagan was elected, trade between the two countries suffered because of expectations that the new president would increase tariffs. Trade relations, however, did begin to improve five years later after Reagan visited China. But the initial downturn in trade relations was largely based on expectations.

Tariff increases announced by Biden in May were expected to take effect on August 1. What role (if any) does Biden’s decision in July to end his presidential re-election campaign have on the economic conflict between the US and China?

- Changing candidates probably doesn’t change the Democratic Party’s approach on trade policy, but it would be worthwhile to hear about this issue from the candidates in the lead-up to the election.

Alessandria: I don’t think the outlook on trade policy changes much with Kamala Harris as the presumptive Democratic nominee, although it would be good for the candidates to discuss these issues. Our economic model recovers estimates of switching between trade war and trade peace from the actions of the firms most affected by these tariffs. These firms probably thought there was a chance that Harris could be president when making their decisions. It would be good for Harris and Trump to debate this issue.

How long do you think the current trade war with China will last?

- Based on the way firms have been changing suppliers, our model predicts there is a less than 20 percent chance the trade war is over by 2025.

Alessandria: Our model estimates that the US-China trade war has a 17 percent chance of ending in 2025, so it will most likely last at least four or five more years. Of course, there’s always a chance that something will break this logjam. It was a big surprise in 1971 when Nixon lifted a 21-year trade embargo on China. Nixon was attempting to get us out of the Vietnam War, and he was hoping the Chinese, who were supporting the Vietnamese, could put some backroom pressure on Vietnam. But it’s not clear what factors exist today that could pull us out of the current trade war.

So, is one party or the other tougher on trade?

- The researchers find a bigger increase in the expected path of tariffs under Biden than under Trump. This is counterintuitive since tariffs rose under the Republicans and did not change under the Democrats.

Alessandria: Our research allows us to recover a time-changing probability of the tariffs the US will apply on Chinese goods. Using those probabilities and the tariffs that products face in war and peace, we can forecast an expected path of future tariffs. And we can make these forecasts at various points in time. In other words, we have a forecast before Trump is elected; when Trump leaves office; and today. These forecasts differ because the trade war has continued and the outlook has shifted based on the state of the economy and relations between the two countries.

Using changes in the path of those forecasts, we can attribute policy changes to different administrations. We find that while Trump raised tariffs, because they were expected to come down quickly, and he changed the distribution of product specific tariffs, when he left office the path of tariffs had fallen compared to when he entered office. In contrast, the path has shifted up under Biden. Some of this is counterintuitive since Trump raised tariffs, but it’s important to remember that firms always believed there could be a US-China trade war and expected tariffs to go up in the future—it just hadn’t happened for a while.

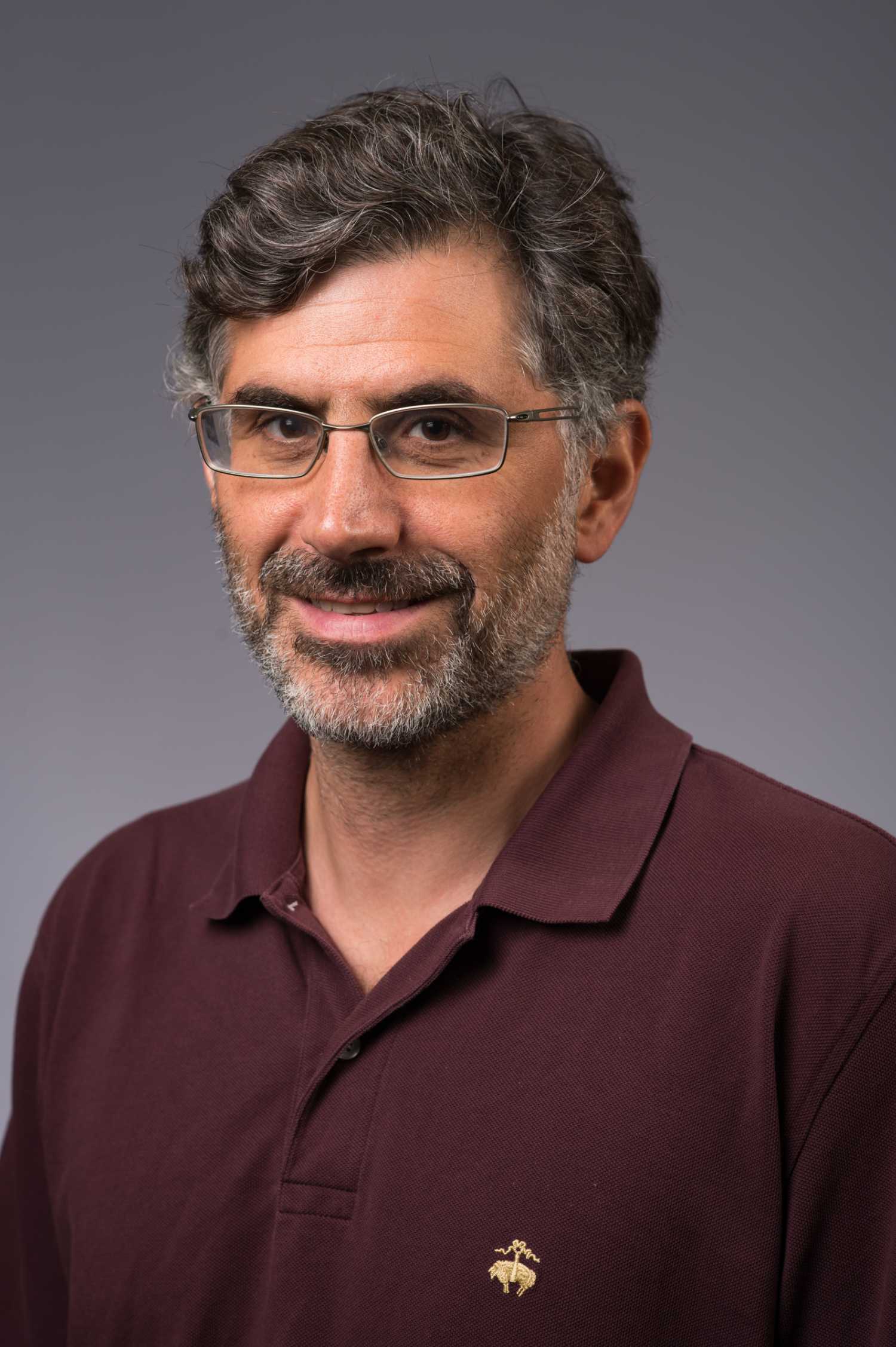

Meet your expert

Professor of Economics George Alessandria is an expert on international trade and finance. Prior to joining the University of Rochester faculty in 2014, he was a senior economic advisor and economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. His research interests are in macroeconomics and international trade. In his use of dynamic models to study trade flows, Alessandria and his peers pioneered a new approach to the field of international trade that allows us to understand the effects of business cycles on trade. Through a microeconomic analysis of the behavior of firms, Alessandria’s work has given insight into what were long-standing puzzles concerning the slow response of trade patterns to economic volatility. He has published in journals such as the Quarterly Journal of Economics, American Economic Review, and the Journal of Monetary Economics. He has served as an associate editor at some of the most prestigious journals in economics.