Infants can use their expectations about the world to rapidly shape their developing brains, researchers have found.

A series of experiments with infants 5 to 7 months old has shown that portions of babies’ brains responsible for visual processing respond not just to the presence of visual stimuli, but also to the mere expectation of visual stimuli, according to researchers from the University of Rochester and the University of South Carolina.

That type of complex neural processing was once thought to happen only in adults—not infants—whose brains are still developing important neural connections.

“We show that in situations of learning and situations of expectations, babies are in fact able to really quickly use their experience to shift the ways different areas of their brain respond to the environment,” said Lauren Emberson, who conducted the study at the University of Rochester’s Baby Lab while a research associate in the department of brain and cognitive sciences.

The researchers exposed one group of infants to a sequential pattern that included a sound—like a honk from a clown horn or a rattle—followed by an image of a red cartoon smiley face. Another group saw and heard the same things, but without any pattern.

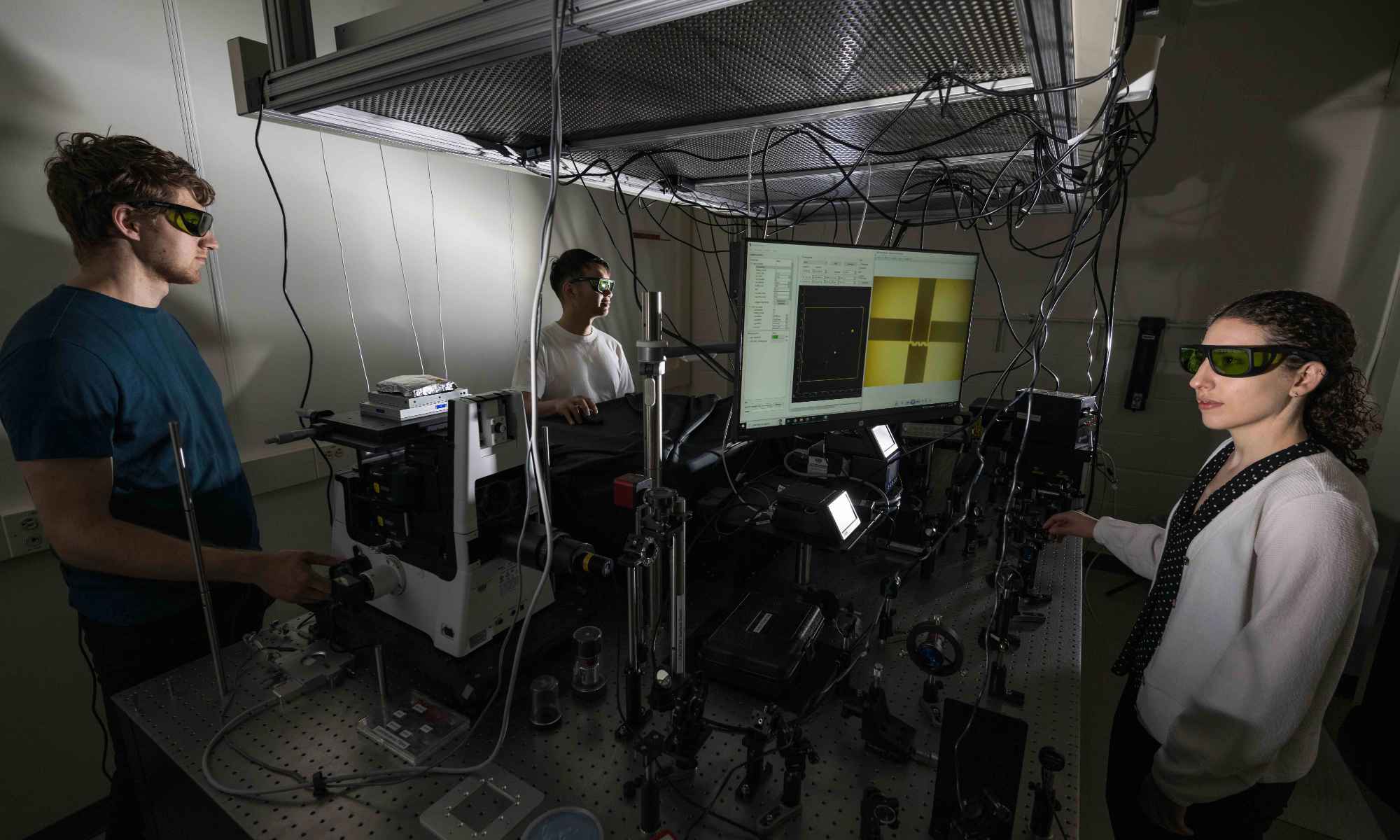

The researchers used functional near-infrared spectroscopy, a technology that measures oxygenation in regions of the brain using light, to assess brain activity as the infants were exposed to the sounds and images.

After exposing the infants to the sounds and image pattern for a little over a minute, the researchers began omitting the image 20 percent of the time. For the infants who had been exposed to the pattern, brain activity was detected in the visual areas of the brain even when the image didn’t appear as expected.

“We find that the visual areas of the infant brain respond both when they see things, which we knew, but also when they expect to see things,” Emberson said.

The finding, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could help shed light on neural development in infants’ brains, the researchers said.

“Part of the reason I wanted to establish this type of phenomenon in infants is because I think it’s a really good candidate mechanism for how infants are using their experiences to develop their brains,” Emberson said. “There’s a lot of work that shows babies do use their experiences to develop. That’s sort of intuitive, especially if you’re a parent, but we have no idea how the brain is actually using the experiences.”

Emberson, an assistant professor in psychology at Princeton University, is continuing to explore the topic by examining the phenomenon in infants who are at risk for poor developmental outcomes, specifically those who were born prematurely. She also is examining whether infants’ visual expectations boost their visual abilities.

Research at the University of Rochester’s Baby Lab relies upon the many Rochester-area families who volunteer to participate in research studies. Parents who are interested in participating can sign up here: http://babylab.bcs.rochester.edu/participate.html.

The other authors are John Richards, University of South Carolina, and Richard Aslin, co-director of the Baby Lab at the University of Rochester. The National Institutes of Child Health and Development supported the research.