A biology PhD student analyzes tanager bird feathers to explore how species evolve over time.

Maria Castaño, a third-year PhD student at the University of Rochester in the lab of Al Uy, a professor of biology, studies populations of birds to understand the processes that lead to the creation of new species.

Castaño collects and analyzes DNA sequences and feathers of tanagers from her native Colombia in South America. Her research focuses on two different subspecies of tanagers, which have different colored feathers on their rump areas: one subspecies lives in the lowlands of Colombia and has yellow rump feathers, while another subspecies lives in the mountains and has red rump feathers.

There are three regions along the edge of the mountains where the two subspecies reproduce, resulting in hybrid tanagers with a gradient of orange feathers. Castaño is investigating tanagers in the three regions to find out if the two subspecies will collapse back into a single population or if the birds are on the way to becoming two entirely new species. At the same time, she is investigating if the genes that determine plumage color are moving from one subspecies into the other using the orange hybrid birds as a “go-between.”

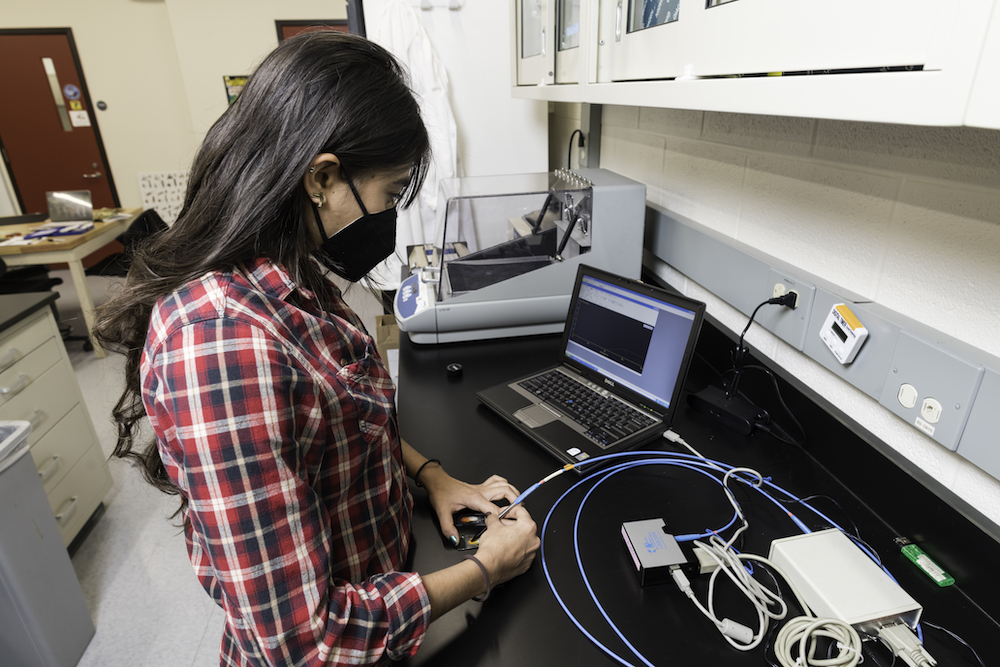

In a biology lab on the River Campus, Castaño uses an instrument called a spectrophotometer to analyze the birds’ feathers. The spectrophotometer allows her to measure the reflectance of the colors in the feather pigments. She hopes to determine how plumage color allows the birds to recognize members of their own species, either to compete or to attract mates. She is also studying if it is plumage color that is keeping the subspecies separate, despite their reproducing.

“I’m trying to describe how the birds’ genes change along the distribution of the species and if the plumage color changes in concert with the genes,” Castaño says. “Ultimately, I want to understand how interbreeding will affect both subspecies’ evolutionary paths.”

Empowering women, supporting conservation efforts

The American Association of University Women recently awarded Castaño the International Doctoral Degree Fellowship for her research in evolutionary biology and her educational initiatives to empower females. A devout birder, Castaño founded her own birdwatching company in Colombia called Amazona Tropical Birding. The company is also involved in conservation efforts to protect the abundance of bird species in Colombia, which has more bird species than anywhere else in the world.

“I strongly believe Colombians should leverage their spectacular diversity and consider birdwatching tourism as a major contributor to the economy,” Castaño says. “Many regions of Colombia remain little explored due to armed conflict in the country that lasted for over 60 years. However, now that a peace deal has opened the door for scientific exploration and Colombia’s biodiversity is promoting curiosity among local and international communities, ecotourism can become a significant source of income for many people. One of the main goals of my fieldwork is supporting local people with their ventures in birdwatching tourism, empowering them with the knowledge that they can earn more by preserving the natural ecosystems than by destroying them.”

Read more

Understanding an endangered species, bird by bird

Understanding an endangered species, bird by bird

Rochester biologist Nancy Chen is mapping the evolutionary forces affecting an endangered species of Florida birds and raising fundamental questions about how and why species go extinct.

Paper wasp parasites turn hosts into long-lived ‘zombies’

Paper wasp parasites turn hosts into long-lived ‘zombies’

University of Rochester undergraduate students and their biology professor study what paper wasps—and the parasites that manipulate them—can tell us about evolution, aging, and group living.

What makes a species different?

What makes a species different?

Rochester research points to the presence of “selfish genes,” whose flow among species may dictate whether two species converge or diverge.