Technology and the mellow scent of wood aren’t often associated with each other in the 21st century. But a new piece of early modern machinery has brought them together in Rossell Hope Robbins Library at the University of Rochester.

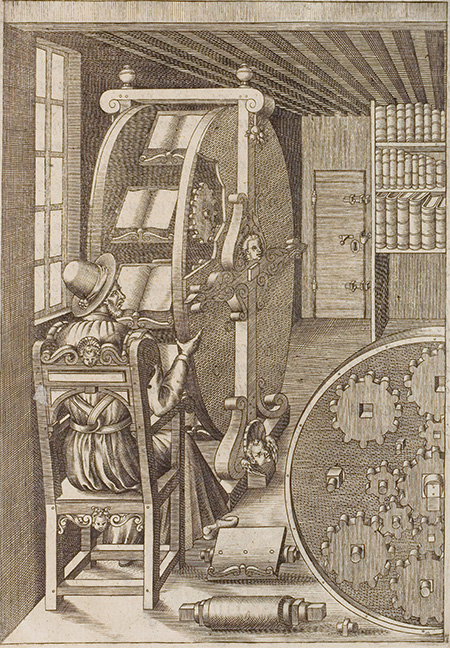

The medieval studies library is now home to a custom-made, full-size book wheel, a kind of rotating bookshelf that was the brainchild of 16th-century Italian military engineer Agostino Ramelli. The device is a “Ferris wheel for old tomes,” says Gregory Heyworth, an associate professor of English and a specialist in textual science. The core of what he calls its “fanciful design” is a system of epicyclic gears in which one gear rotates around another—like a planetary system—with the device’s shelves maintaining a constant 45-degree incline that hold the books securely as the giant wheel turns.

“It’s an incredibly beautiful and historically accurate machine that we’ll be able to use to teach the history of the book and reading technologies during the medieval and early modern eras, the history of engineering and technology, material culture, and more,” says Anna Siebach-Larsen, the director of the Robbins Library—which has comprehensive holdings in all aspects of medieval history, literature, art, and culture—and the Koller-Collins Center for English Studies.

The wheel was a tool for producing early encyclopedias and editions of classical works, “tasks that require having many books open simultaneously so that information from multiple sources can easily be collated,” says Heyworth. It’s the same kind of need that prompts modern-day information seekers to open multiple tabs in a browser.

A happy convergence of engineering and the humanities, the wheel is tangible evidence of a growing collaboration between the University and the nearby Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). The Robbins Library and the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at RIT share a similar focus on the history of the book across the Middle Ages and into the early days of printing—and beyond, in the case of the Cary Collection. Heyworth had long dreamed of building a book wheel based on Ramelli’s design, and the project evolved from conversations between him; Siebach-Larsen; Steven Galbraith, curator of the Cary Collection; and Jessica Lacher-Feldman, assistant dean and director of Rare Books and Special Collections at the University of Rochester.

“Rochester is rich with cultural and historical collections, and working with RIT on projects such as this only adds to the experiences we can help create for students, faculty and the community,” says Lacher-Feldman. “As we continue to think creatively about how to connect with the past, we become stronger and more dynamic as an institution.”

As a senior project, Ian Kurtz, Reese Salen, Matt Nygren, and Maher Abdelkawi—mechanical engineering students at RIT—worked for a year to build two book wheels, one for Robbins Library and another for the Cary Collection. Students in Heyworth’s Digital Media Studies and Medieval Idea of the Book courses are developing a digital kiosk to explain to Robbins Library visitors the book wheel’s history and mechanics. The wheel itself will serve as display space, offering literally rotating exhibits of works in the library’s collection.

Siebach-Larsen describes Ramelli’s design as an opportunity for him “to display his engineering prowess.” Bringing his design to life was a chance for the engineering students to do the same—and to delve into history. They developed plans based on Ramelli’s 1588 design, sourcing woods—European beech and white oak—in common use in Northern Europe in the early modern period, and they carefully considered when to hew to historical accuracy and when to make improvements to serve their clients.

The project exemplifies the interactions Siebach-Larsen would like to foster between the Robbins Library and the University’s own engineering community. Her eyes light up when she considers the possibilities: working models of the universe’s structure, as imagined by medieval thinkers; a replica of a Gothic building, complete with difficult-to-replicate Gothic arches; a siege-warfare machine. “I’d love to work with optics and engineering students to see if we can delve into medieval theories of optics and try to recreate their ‘vision’ of how vision worked,” she adds.

Such blending of the humanities with science and engineering can help students and researchers understand ideas that can be difficult to conceptualize through reading alone. “It brings them to life in a totally different way,” she says.

The history of technology is an area of increasing focus in the collections of the University’s libraries. And she hopes that the book wheel will whet visitors’ appetite to look even earlier and learn about breakthroughs of the Middle Ages, so often thought of as a scientifically fallow age. “There were so many technological innovations,” she says. “I’d love to break down those biases.”

And she hopes visitors will take advantage of a hands-on experience, too. “I want people to try it for themselves,” she says.

Turning the massive wheel is an invigorating experience, both physically and intellectually. “The book wheel shows readers how scholars were trying to improve the technology for gaining easy access to information in books in an analog world,” says Heyworth.

He sees strong intimations of the future in the arrival of the wheel, too. It’s the fruit of Siebach-Larsen’s vision for Robbins Library as a place “where people experience books and literary culture as much with their hands as with their minds.”