Thompson was a longtime University leader and a pioneer in optics and holography.

The University of Rochester community is remembering Brian J. Thompson, a dean emeritus and professor emeritus of optics who is known for his pioneering research in holography. Thompson died on January 27, in Fort Myers, Florida. He was 91.

Thompson was born in England and received his PhD at Manchester University. The William F. May Professor of Engineering filled many roles in his career at Rochester, beginning in 1968 as the director of the Institute of Optics. He held the position until 1975, when he became dean of what was known as the College of Engineering and Applied Science. In 1984, he became provost and served in that capacity until retiring from the position in 1994. He helped shape the University’s growth in numerous ways throughout that period.

“Brian was one of many people from the Institute of Optics who helped LLE get started with optics, research, and communication,” says Tom Bristow PhD ’73 (physics), the former manager of the University’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics and founding president of Chapman Instruments. Bristow worked closely with Thompson for several years as assistant dean for special programs. “He was a marvelous man who was welcoming to everyone he interacted with—staff, students, and faculty. He taught me so much, his organizational skills were superb, and he was one of the best listeners of the faculty at the University.”

Thompson was an active researcher while serving as an administrator, with deep expertise in coherent optics, holography, phase microscopy, and image processing. He was the author of more than 180 scientific and technical papers, and his experimental studies on partially coherent light and its effects became standard works in the literature of the field. His illustrations of these and other optical phenomena appeared widely in optical textbooks and other works dealing with coherent optics. Thompson also developed the first direct application of holography, dynamic particle size analysis, which is now used in a range of fields.

“I believe you need to be teaching something you really understand,” Thompson said in 2009. “If you’re not involved at the cutting edge, all you’re doing is interpreting what’s in the textbook. I wanted to convey, through experimentation and theoretical knowledge, physical insight. It was always about insight.”

His students remember him as a highly organized and engaging lecturer. Professor Jim Zavislan, who began under Thompson’s tutelage as an undergraduate optics student, says Thompson expected his students to take good notes and that his lessons continue to serve as a source of inspiration.

“I remember vividly a time when I made an appointment to discuss a question I had in his class,” says Zavislan. “As I arrived for my appointment, Professor Thompson asked to first see my class notes prior to allowing me to ask my question. He reviewed them and asked me to state my question. I did so, and then he smiled and pushed my notebook toward me and said, ‘The answer to your question is in your notes.’ He then turned to resume what he had been doing. Bewildered, I walked out of his office, sat down, and reflected on my question and realized that indeed my question was answered in my notes. It was a powerful reminder of the importance of reflection and review in learning new material, and it is a lesson I work to instill in students today.”

Thompson was the thesis advisor for Laura Weller-Brophy, a business consultant in optical technologies and intellectual property, while she was working on her master’s degree in optics. She credits him with teaching her scholarly writing and fostering a positive faculty-student dynamic at the University.

“I knew him as an articulate and expert teacher and grew to appreciate him as a valued mentor,” she says. “I marvel at the high quality of his work, with measurements made several decades before mine having stunning precision. He taught me to honor scientific honesty, encouraging unexpected results to be reported frankly so that their value might be pondered in the future. He was also an honorable, kind, and generous human being. Whenever we would see each other, he was certain to greet me warmly, inquiring not only about my work, but about me and my family. He did me the honor of expecting much of the same from me.”

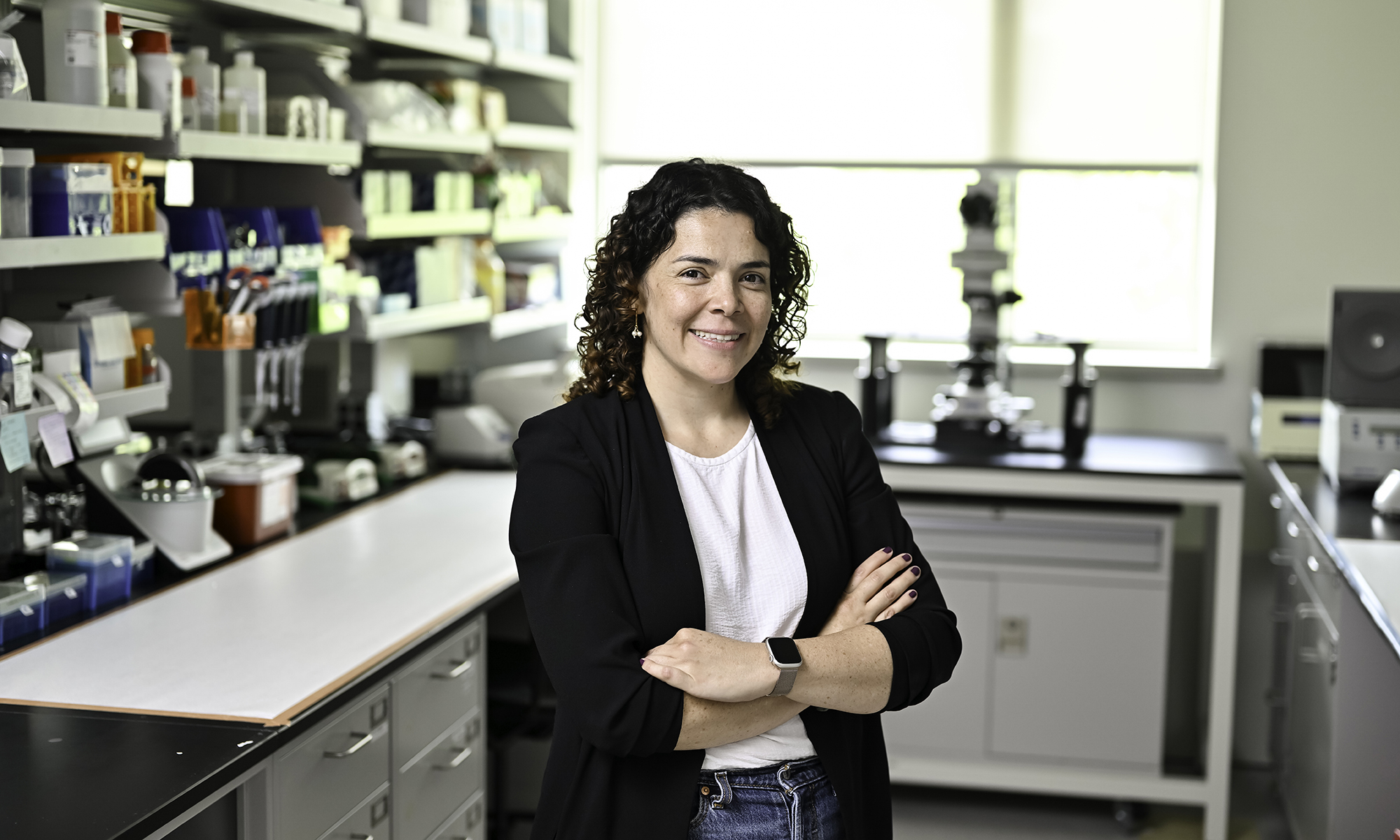

Some of Thompson’s other lasting influences on the University include establishing the University of Rochester Press and serving on the University’s Arboretum Committee, where his work helped to beautify the campus. In 2009, the University created the Brian J. Thompson Professorship in Optical Engineering, established by John Bruning, former CEO of Corning Tropel Corp. The professorship is now held by Jannick Rolland, a pioneer in freeform optics and director of the Center for Freeform Optics.