The effects of the Pearl Harbor bombing on Rochester campus life were swift and profound.

On December 4, 1941, the Campus, the newspaper of the College for Men, declared a state of boredom on the University of Rochester’s River Campus.

“Beside the muddy, turbid Genesee, it has been a dull week,” the paper reported. “Nobody spoke out of turn, nobody won unusual honors, nobody jumped off the top of Rush Rhees tower.”

Special Feature: Rochester at War

Contents

- The College for Women steps up

- Institute of Optics designs devices for night warfare (article and video)

- Rochester research and the war effort

- Pros and Cons: A prewar debate on propaganda (c. 1940 audio recording)

That same week, at the Prince Street Campus, students at the College for Women were immersed in planning their annual winter formal dance.

On Sunday, December 7, life changed starkly for both the men and the women.

Rarely had there been such a swift change of mood on the River Campus. In the issue following the Sunday morning attack, the Campus lamented that the firestorm had brought “the ivory tower tumbling down about the youth of this generation.”

It’s true that the previous September, President Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed the Selective Service and Training Act, requiring all male citizens 21 to 36 to register in the first peacetime draft in American history. But the president presided over a nation reluctant to become entangled in foreign wars. Students at the College for Men could go about their business confident that, for the most part, the war engulfing Europe and Asia would remain a distant threat.

In some ways, it had even been an opportunity. In the fall of 1940, Roosevelt proposed and won broad congressional support for the so-called lend-lease program to provide military supplies to any nation deemed vital to American interests.

As the United States began supplying materials primarily to Britain, an even more important development for research universities like Rochester was Roosevelt’s June 1941 executive order establishing the Office of Scientific Research and Development. By September, University scientists had assumed leading roles in the national defense program. Nuclear physicist Lee DuBridge was named director of the Radiation Laboratory at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where more than 3,500 scientists would develop highly effective microwave radar technology.

The days after the Pearl Harbor bombing were anxious ones on the River Campus. There were some signs of normalcy—basketball games, holiday dances, announcements of Dean’s List honorees, and the annual Boar’s Head dinner—but life had changed. University President Alan Valentine put it starkly.

“Our country is now completely involved in an all-out world war,” he told the students. “The survival of our nation and our ideals is clearly at stake.”

The federal government emphasized a need for trained engineers and chemists and urged students to stay in college.

“When your country needs you, it will give you a clear personal call,” Valentine told students. “Until then, stay where you are and do your job well.”

Many students on the River Campus gave up their dorm rooms to Army aviation cadets undergoing training as well as dozens of men being trained as Naval photographic technicians.

Buildings across campus were transformed into spaces for national defense work.

The first of several city-wide “blackouts”—protection from possible air attacks—took place one week after the Pearl Harbor attack. At 6:15 p.m., superintendent of maintenance Charles Livingstone pulled the master switch to cut all power, plunging the River Campus into darkness. In the black sky, only the red winglights from the Gannett Newspapers plane could be seen. It carried city officials examining the blackout’s effectiveness.

The next day, all students were summoned to Morey Hall to fill out cards stating their draft status. US defense savings stamps went on sale in Todd Union—for 10 cents, 25 cents, 50 cents and $1. They could be turned in for defense bonds, which started at $18.75.

“It will cost money to defeat Japan,” read a notice in the Campus.

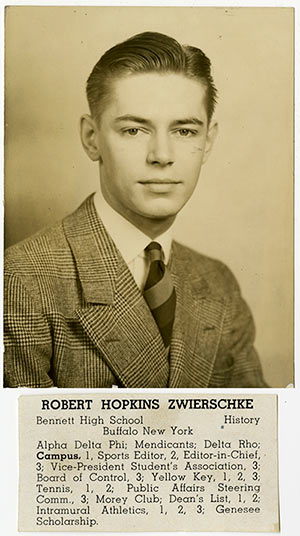

Before Pearl Harbor, the campus community in large part mirrored the nation’s isolationist views. “Young men have no burning desire to act as receivers for machine-gun fire,” a Campus editorial from April 21, 1939, declared. The writer, Robert Zwierschke ’39, would be the first Rochester alumnus to lose his life in World War II, going down with the aircraft carrier Lexington in the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 8, 1942. He would be one of 57 University alumni to die in the war. A memorial plaque in Wilson Commons lists each of their names.

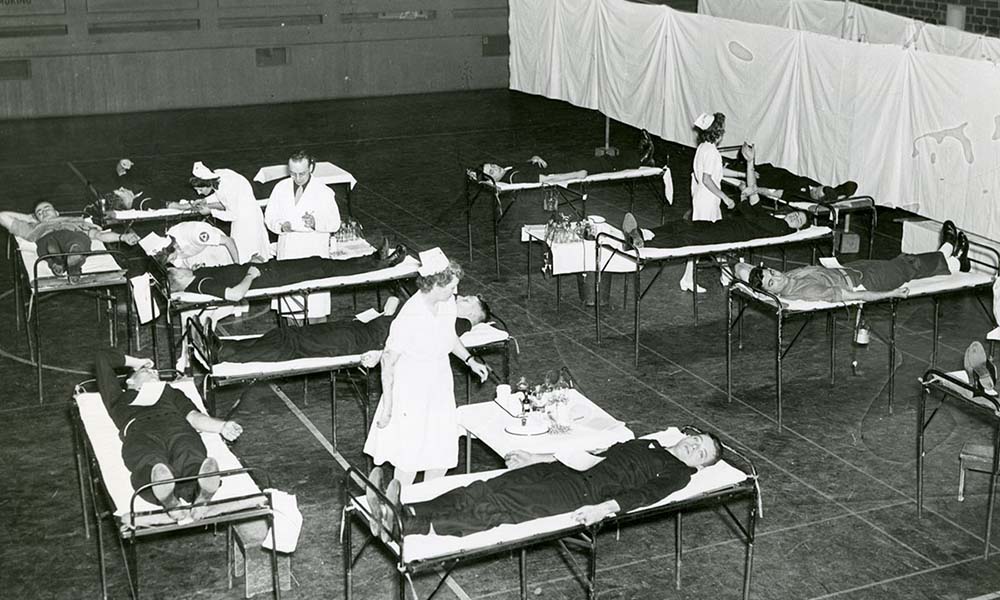

Blood drives were set up after the Army and Navy requested 200,000 donations. Carl Lauterbach ’25, vocational counselor for men, was in charge of civilian defense at the University and assigned “spotters” to watch for enemy raids. On weekends, University students, professors, and staffers collected and sorted scrap. To aid one drive, Valentine used a sledgehammer to knock down an iron fence near the George Eastman mansion on East Avenue, which served as the president’s official residence at that time.

Rations for food and gasoline were enforced across the nation. Valentine began riding his bicycle to work, a three-mile trek from home, and many faculty members followed suit. When Valentine missed a train connection to address a school of nurses in Pennsylvania, he hitched a ride with a farmer and barely arrived at his destination on time.

During winter recess, the senior faculty voted to compress four academic years into three, with a summer session set to begin May 15 and end August 7 (at $13.30 per credit hour).

“Summer vacation is war victim,” read the headline in the December 1941-January 1942 issue of Rochester Review. So were the 1942 golf, tennis, and baseball 1942 seasons, which were canceled due to the accelerated timeline.

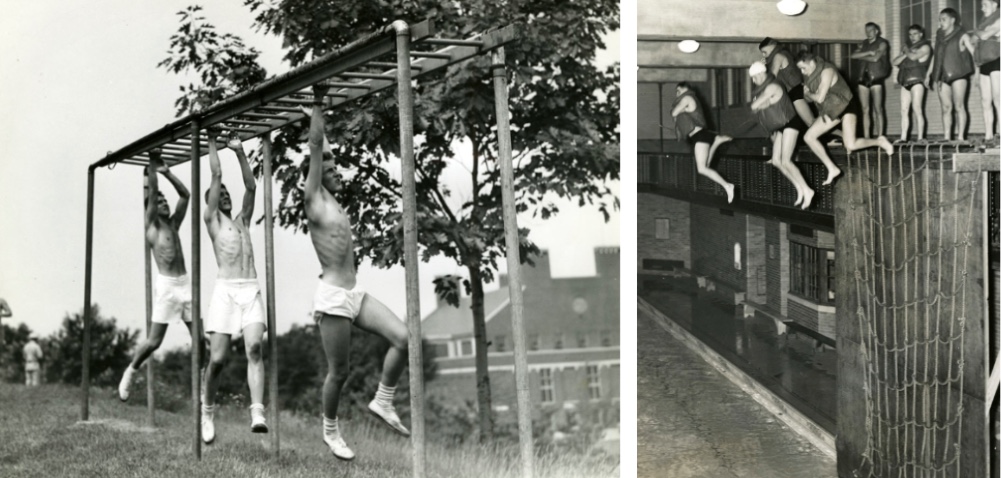

The faculty also approved a plan requiring the men to take four years of physical education instead of two, with an emphasis on contact sports, boxing, wrestling, and obstacle courses. All students had to demonstrate an ability to swim and also float on the water’s surface for one hour. Swim coach Roman (Speed) Speegle asked, “How many of our boys died at Pearl Harbor because they didn’t know how to keep themselves afloat long enough for rescuers to reach them?” He followed up by offering lessons to any young man in the Rochester area facing induction who didn’t know how to swim.

University secretary Anne Newhall had been on vacation in Hawaii and witnessed the Pearl Harbor assault.

“The attack came as a complete surprise to everyone in Oahu,” she recounted in a Campus article. “At first, I thought it was only air raid practice, but after a few minutes, the planes grew much nearer and we started to hear anti-aircraft fire.”

A fort next to the house where Newhall stayed was hit. She saved a piece of shrapnel and brought it to Rochester—a powerful symbol of the war that had been brought home to America.

—Jim Mandelaro

…with able support from the College for Women

As news of the attack reached the Prince Street campus, discussion turned quickly to ways in which the women could contribute to the war effort.

“How can we, young ladies of the war class of the University of Rochester, assist in this great struggle?” posed a student editorial in the January 1942 Tower Times, the newspaper of the College for Women. “Certainly not by expecting to live our own peaceful, normal lives. Times have changed and will continue to change. We must realize this and be ready for it.”

The students took some immediate steps, first turning the annual winter formal into a dance fundraiser for the Red Cross. They set up knitting drives, sold war stamps, and collected scrap metal. They intensified these efforts in subsequent months as men were called away for military service and industries expanded to meet war demands.

In light of an amplified need for medical professionals, female students and alumni were urged to take the Nurses’ Aid Course of the American Red Cross, offered at Strong Memorial Hospital. Course graduates were able to work alongside nurses and doctors, monitoring vital signs and assisting with dressings, casts, and slings.

Similarly, at the beginning of January 1942, the Women’s Athletic Association hosted a 10-week course, Red Cross First Aid and Lifesaving, in Cutler Union, with instruction in accident prevention, breathing restoration, stoppage of bleeding, and bandaging of broken bones.

The women formed a War Activities Board to highlight various campus initiatives and opportunities to assist the war effort, including calls to fill many factory supervisor and industrial lab technician jobs typically held by men.

In the fall of 1942, Kenneth Ogden of the Kodak Hawk-Eye Works—which was heavily involved in making optical products for the military—headlined a luncheon on the Prince Street Campus to outline opportunities for women. “Some 20,000 more workers will be required to meet the demands of Rochester industries before the end of the year and at least 50 percent will have to be women,” according to a Tower Times article reporting on the event. Women were encouraged to fill these roles while continuing to attend classes at the College.

The College responded by offering “war minors” that explicitly encouraged women to expand their liberal arts educations by taking courses in mechanics, mathematics, psychology, physics, engineering, accounting, and statistics. Women with war minors found jobs waiting for them upon graduation. Students who completed the war minor course in mapmaking, for instance, were “guaranteed jobs as engineering aides in the mapmaking division of the War Department,” boasted an article in the Rochester Alumni-Alumnae Review. Rochester was one of the few leading universities in the United States to offer these mapmaking courses.

At the end of the war, in September 1945, the School of Medicine and Dentistry admitted 13 females, its largest ever class of women, and more than double the number of women in any previous entering class. George Packer Berry, assistant dean of the school, lauded the milestone: “They [women] have shown during the war that they can do as good a job as the men in many activities that formerly were considered exclusively the male province. As a result of their war endeavors, more women have become greatly interested in medicine and other fields of science, and the indications are that they are going to take an increasingly important part in them.”

—Lindsey Valich

Institute of Optics designed devices for night warfare

The night after Pearl Harbor was attacked, Brian O’Brien, director of the Institute of Optics at the University of Rochester, took off in a seaplane from the Naval Air Station at Norfolk, Virginia, with several of his staff.

They wanted to test a new night binocular they had developed for Britain’s Royal Air Force, so that its fighter pilots could engage German bombers at night without shooting down their squadron mates by mistake.

The station’s antiaircraft defenses, informed of the test flight, had been ordered not to turn on searchlights. However, because of the Pearl Harbor attack, “everyone at the station had the jitters, and rumors were flying about thick and fast,” O’Brien later wrote.

At each pass over Hampton Roads “a dozen dazzling fingers of light, half a billion candlepower each, would hit us with the impact of something solid,” O’Brien wrote. In desperation, the seaplane and its target plane headed farther out to sea to complete the test.

The institute was among the nation’s most important centers of scientific research during World War II. A major impetus for its creation had been the over reliance of the American military on German optical instruments and expertise prior to the First World War. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Office of Scientific Research and Development in June 1940, O’Brien became a leader in its formation.

By the time the United States formally entered the war, O’Brien and his colleagues at the institute had “essentially initiated the whole science of night warfare,” writes faculty member Carlos Stroud in A Jewel in the Crown, the history of the institute that he cowrote and edited. By war’s end, about half of the country’s university-based military optics research projects were conducted at the University of Rochester. Even the ceramic kilns of the University’s Memorial Art Gallery were taken over for molding aspheric lenses for aerial cameras, Stroud notes.

Around the University, security was tight. The fourth floor of Bausch and Lomb, for example, was sealed off behind a cordon of wire grill and guarded 24 hours a day. George Fraley, O’Brien’s assistant, carried a pistol with him when he took surplus classified documents to the hospital incinerator.

Some 50 scientists, engineers, undergraduates, and technicians were handed military projects that often progressed from problem to prototype in a matter of months.

They provided US pilots, submariners, snipers, and engineers with an array of night vision devices, glare resistant sun goggles and gun sights–even fluorescent reflectors to safely illuminate roads and runways in combat zones.

No longer would Germany enjoy a technological advantage in the field of optics. Little more than 20 years into its life, the institute helped ensure that during the Second World War, the Allies could rely entirely on themselves.

—Bob Marcotte

Rochester researchers and the war effort

Wallace Fenn, physiology: provided critical information in the development of pressurizing masks for pilots

Edward Adolph, physiology: studied hydration for soldiers involved in desert warfare

Quentin D. Singewald, geology: conducted investigations on strategic war minerals in South America for the US Geological Survey

J. Edward Hoffmeister, geology, dean of the College: directed charting projects for the Army Map Service

Raymond V. Bowers, sociology: served as a senior statistician to the Selective Service chief

Sterling Callisen and George Raser, Romance languages: assisted the Office of Naval Intelligence

Frank J. Smith and William D. Dunkman, economics: consulted for the federal Office of Price Administration

John R. Russell, director of University libraries: led the American Library Association committee to aid war-torn libraries in Europe and Asia

The School of Medicine and Dentistry was one of about a dozen centers in the United States serving as repositories of dried blood plasma for civilian emergencies; other medical school researchers studied psychological and physiological effects of war wounds and improved methods of plastic surgery for disfiguring wounds and burns.

Pros and cons: A pre-war debate on propaganda

The audio below is taken from an episode of a Rochester-area 1939 or 1940 radio program called “Pros and Cons,” in which five University of Rochester professors (including President Alan Valentine) and a newspaper editor discuss the troubling rise of war propaganda prior to WWII—or as they called it at the time, “the conflict.” Participants include Alan Valentine, University president; Richard Greene, Department of English; John Pendleton, Department of English; Willson Coates, Department of History; Elliot Hutchinson, Department of Psychology; and M.V. Atwood, associate editor, Gannett Newspapers.

Read more

Winston Churchill addresses the Class of 1941 by radio

Winston Churchill addresses the Class of 1941 by radioThe University has a proud past of commencement speakers and honorees but the 91st commencement ceremony on June 16, 1941, was particularly noteworthy.

Bringing recognition to a forgotten group of women veterans

Bringing recognition to a forgotten group of women veteransTiffany Miller ’00 and her family worked for years to successfully overturn a ruling that prohibited World War II Women Airforce Service Pilots from being buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

‘For some of us, every day is Memorial Day’

‘For some of us, every day is Memorial Day’Members of the University of Rochester community have served in the United States military—and lost their lives in that service—almost since the University was founded in 1850.