Rochester undergraduates and their professor study what paper wasps—and the parasites that manipulate them—can tell us about evolution, aging, and group living.

Wasps are social insects that work together to benefit their hive. When a parasitic insect called Xenos peckii infects certain species of paper wasps, however, something incredible happens: the parasite manipulates the wasp’s brain so the wasp loses its social instincts and abandons its colony. The parasite also manipulates the wasp’s genes to increase the wasp’s lifespan.

This relationship between parasites and wasps makes them an ideal natural experiment for scientists such as Floria Mora-Kepfer Uy, a research assistant professor of biology at the University of Rochester. She aims to better understand what genes are involved in social behavior and aging, not only in insects, but also in human beings.

“Wasp societies have remarkable similarities to human societies, so we use them as a model system to understand which mechanisms are responsible for social behavior, physiology, and aging,” Uy says. “It’s amazing that a parasite has evolved to make these wasps lose their social instincts and behavior, while manipulating their aging process. It allows us to study very important questions of genes that affect biological processes that can directly relate to human societies and their health.”

The research is part of Uy’s larger body of work exploring the evolution of cooperation and group living, including the relationship between brain development and sociality.

This summer, Uy and a group of undergraduate students collected both native Northern paper wasps (Polistes fuscatus) and invasive European paper wasps (Polistes dominula) at several sites throughout New York, including Genesee Valley Park in Rochester and Robert H. Treman State Park in Ithaca. The researchers hope to reveal the mechanisms that parasites use to manipulate their host’s brains, behavior, and physiology.

Photos by University of Rochester photographer J. Adam Fenster.

NOTHING BUT NET: Team Wasp begins the collection process

Research Assistant Professor of Biology Floria Mora-Kepfer Uy (far right) and undergraduate students Eisabella Sherwood ’23 (left), Joseph Krell ’24, and Federico Sánchez-Vargas ’23 (T5) (right), discuss techniques for collecting European paper wasps, an invasive wasp species, in Genesee Valley Park in Rochester.

The members of Uy’s lab call themselves “Team Wasp,” according to Uy. “It’s so much fun for us to be the lab at the University of Rochester that studies social wasps and represents our yellow jacket mascot, Rocky.”

EYES ON THE PRIZE: The team spots a wasp’s nest

The student researchers collect paper wasps infected with parasites and bring them back to Uy’s lab on campus to study how the parasites affect their hosts’ brains. The parasite’s main goal is to increase how many offspring it has. To do this, it needs to develop inside a host that lives long enough for the parasite to complete its own growing cycle. The parasite therefore infects and alters its host wasp’s genes to make the wasp live longer, so the parasite itself will live longer. It then manipulates the wasp to abandon its hive to find nests with host larvae to infect.

“The parasite needs the wasp to survive long enough to manipulate its brain and allocate all of its resources to the parasite’s babies, not to being social,” Uy says. “The parasites turn the wasps into these weird zombies.”

GREEN SCENE: Contributing to conservation efforts

In addition to collecting European paper wasps in Genesee Valley Park, Uy collects Northern paper wasps, a species native to North America, in Robert H. Treman State Park in Ithaca, New York. Uy has found invasive European wasp species in Genesee Valley Park and other upstate NY sites, but she has yet to find evidence that the invasive wasps have made it to Treman State Park, about 90 miles away. Uy and her team collect and monitor native paper wasps at this park, which also helps with conservation efforts.

“We have a nice synergy with the park team,” Uy says. “I dabble in several research areas, but one of the most important things for me is climate change and conservation. We have a couple of invasive species locally that do affect the native species.”

CLEAN SWEEP: Using a bug vacuum to collect wasps

Sherwood, an ecology and evolutionary biology major, uses a special vacuum device to collect a wasp as Sánchez-Vargas and Krell look on. “Conducting independent research in Dr. Uy’s lab has been one of the best decisions I made at UR,” Sherwood says. “I now have experience not only in a lab environment, but also in organizing and performing an entire research project. It’s made me surer of what I want to do in the future and what career I’d like to pursue. I definitely feel more confident as a scientist and a student.”

LINE OF SIGHT: Looking for parasites

Uy uses a magnifying glass to determine if a wasp hosts a parasite. On their native continent, European paper wasps are attacked by their own native parasite, Xenos vesparum. And in North America, native paper wasps are attacked by their native parasite, Xenos peckii.

“In other words,” Uy says, “each wasp has its own parasitic insect in its native range. One of the things we are investigating is why the North American native parasite infects only the native host and has not also infected the invasive European paper wasp.”

STOMACH BUG: A native paper wasp infected with a parasite

The researchers can tell if wasps are infected by parasites because the wasps show “strong symptoms,” Uy says, including aberrant behavior and bumps in their abdomens where the parasites are lodged. Above, a native paper wasp is infected with the parasite Xenos peckii, which protrudes from its abdomen.

SPECIAL DELIVERY: Preparing a nest for transfer

Sánchez-Vargas prepares a nest to transfer it to the lab. For the past few years, Sánchez-Vargas has been studying how a parasite chooses its host and how parasitic infections affect a colony. For instance, he found that before abandoning its hive, an infected wasp becomes “a freeloader,” he says, “taking resources and contributing nothing back to its hive. Part of my work is asking what happens to the success of a group when individual members are sick and all the responsibilities fall on those that aren’t sick—an issue that certainly extends beyond insect societies.”

NATURE’S NEST EGG: A paper wasp’s nest, complete with larvae to infect

When the parasite mom is ready to release its larvae, it makes the infected wasp abandon its hive to find other hives to infect. Sánchez-Vargas also conducted experiments in which he had the right nest (that of a native wasp) and the wrong nest (that of an invasive wasp). The wasp infected with the native parasite always chose to land on the native nest—the “right nest”—to release its larvae.

“The parasite mom is very smart,” Uy says. “It can manipulate the native wasp to find other native wasp nests to infect, and to always deposit the parasite larvae in the right host.”

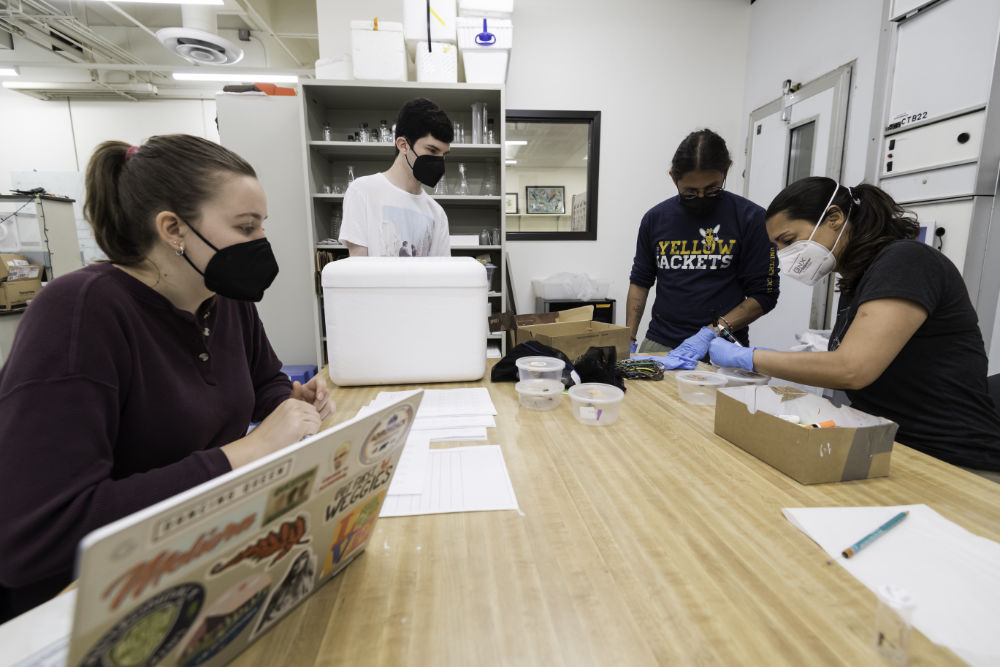

HIVE MIND: Cataloguing wasps back at the lab

Back at Uy’s lab on the University’s River Campus, the researchers catalogue the wasps and rejoin them with their respective nests.

“What I have valued most during my time at the Uy lab has been the opportunity to function as an independent investigator,” says Sánchez-Vargas, who conducted this research as an undergraduate student. “I’ve been involved at essentially all stages of the work: from conceptualizing and solidifying research questions, developing methods, collecting data, analyzing it, and writing it up. This has given me the opportunity to grow greatly as a young scientist.”

ABOVE (CARD)BOARD: Preparing the nests

The students glue nests to pieces of cardboard that they then mount inside enclosures for further study. In the lab and in the field, the researchers wear several types of gloves to avoid being stung by wasps.

“Once in a while, we get an occasional sting, but we try to avoid those as much as possible through training in handling wasps,” Uy says.

HOME AWAY FROM HOME: ‘Wasp central’ at Hutchison Hall

Krell, Sánchez-Vargas, and Sherwood prepare wasp enclosures in the greenhouse attached to Hutchison Hall on the River Campus. The researchers have turned the greenhouse into “wasp central,” Uy says, with rows of enclosures for the wasps. This setup allows Uy and her students to study different aspects of the wasp-parasite relationship. For instance, Sánchez-Vargas ’23 and Maggie Kane ’22, conducted studies using experimentally infected native and “Frankenstein” wasps.

“All of these experiments were conducted by undergraduates, but this is graduate-level work,” Uy says.

ZOOM IN: Examining wasps under a microscope

Under a microscope, the researchers view the parasite Xenos peckii attached to the side of the larvae of a Northern paper wasp.

“Social insects like wasps are a great model organism,” Uy says. “During the pandemic, humans experienced the multiple effects of social isolation. We know the brains of the wasps we work with are really affected when they don’t have social interactions, same as what happens with humans. We have all these amazing parallels that we can compare.”

Q&A: The making of “Frankenstein” paper wasps

As undergraduate students, Maggie Kane ’22 and Federico Sánchez-Vargas ’23 (T5) conducted research in the lab of Professor Floria Mora-Kepfer Uy to create “Frankenstein” wasps. In the wild, a native parasite does not infect an invasive paper wasp, and the researchers wanted to understand why.

Kane experimentally infected the “wrong” host—invasive European paper wasps—with the native wasp parasite Xenos peckii, confirming infection is feasible. Sánchez-Vargas then took native infected wasps and gave the parasite the choice of a native host nest or an invasive host nest. The native parasite always made its host choose the native wasp nest.

“The reason we don’t see European wasps infected with native parasites in the wild is because the parasite mom manipulates its host to use odor and visual cues to go to the right place—a native wasp nest—to release her babies,” Uy says. “The larvae never get dropped off at the wrong nest (the invasive species). This is a level of sophistication where the parasite recognizes and knows where it needs to go to ensure its survival.”

Kane, who recently started graduate school in molecular biology at Columbia University, and Sánchez-Vargas, now a Take Five student at Rochester, discuss these studies and how they benefited from conducting research as undergraduate students.

Can you briefly summarize your research with “Frankenstein” paper wasps?

Kane: We studied a host-parasite system where the host is a wasp and the parasite is a very small insect that lives within the wasp. The parasite is able to change the behavior and physiology of the wasp, such as making it lazier, increasing its fat bodies, castrating it, and increasing its lifespan, all so that the parasite can grow and reproduce.

Our main wasp of interest is native to the United States. Interestingly, there is a parallel host-parasite system in Europe, and its host wasp is invasive to the US. While the two systems are so similar, we have never observed the invasive wasp to be parasitized by the native parasite in nature. Fede [Sánchez-Vargas] and I were interested in why that is and how this parasite has maintained its host specificity.

Sánchez-Vargas: My research was focused on several things, including: How does the parasite know how to choose the right host, when many are available but only one is the right “home”? I’ve found that amazingly enough, the parasite Xenos peckii manipulates its host to make the choice for it, taking it to other native wasps’ nests where it can deliver baby parasites to infect a new generation of wasps.

Why is this research into paper wasps and their parasites important?

Kane: The success of an invasive species is often attributed to a loss of predators. Our experiments help us better understand how an invasive species deals with or evades predators. Also, by determining how these wasps evade parasitism and how the parasites work to get around such defenses, we can get a better understanding of many other host-parasite systems, not just invasive ones.

Sánchez-Vargas: One of the most interesting kinds of natural relationships between organisms is the parasite-host dynamic, where one animal (the parasite) exploits another (the host) for its own benefit. Because this is a pretty nasty arrangement, parasites have to evolve quite nifty solutions to be able to maintain their place in the race against getting outsmarted by their host. For one, understanding parasitic relationships can teach us a lot about disease at large.

What made you interested in this type of research?

Kane: I have always loved nature and animals. In college I was interested in biological research; however, I wasn’t sure I wanted to focus solely on molecular biology. Dr. Uy’s lab seemed like a great mix of a wet lab and field research. I got to do so many cool things, such as catching and handling wasps, that I never would have done in a classical molecular biology lab.

Sánchez-Vargas: Dr. Uy asks “ultimate” questions about why things in the natural world are as they are, and how they can be explained in evolutionary terms. The natural world is beautiful in its complexity, not just in the massive numbers of species out there but in the diversity and variety of their behavior. I chose to work with Dr. Uy because I knew I would learn the questions and techniques that scientists use to understand this diversity.

Maggie, how did this experience help prepare you for graduate school?

Kane: Dr. Uy is a very hands-on and invested mentor. I learned everything from how to read a scientific paper, to designing experiments, to analyzing and interpreting results. I was able to immerse myself in the scientific process, while learning just how much hard work and dedication research takes. Dr. Uy invested a lot of time into me becoming an independent researcher, and these experiences helped me realize my passion for research and love of science.