A Rochester political scientist explains why the ‘clash of ideas’ resulting from free speech is necessary for a well-functioning university.

In September, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression released a survey of undergraduates on college campuses across the United States in an effort to gauge the state of free speech and expression in American higher education. Recruiting students from the College Pulse American College Student Panel, the organization sought to measure how comfortable students were in discussing controversial topics in various campus settings; how tolerant they were of campus speakers whose views were offensive to liberals; how tolerant they were of campus speakers whose views were offensive to conservatives; and how well or how poorly their institutions’ administration did in supporting a culture of free expression.

About David Primo

An expert on campaign finance laws, the federal debt, corporate social responsibility, and budget rules, David Primo is the author or coauthor of several books, including Rules and Restraint: Government Spending and the Design of Institutions (University of Chicago Press, 2007) and Campaign Finance and American Democracy: What the Public Really Thinks and Why It Matters (University of Chicago Press, 2020).

Among those polled were 250 University of Rochester students. Twenty-seven percent of the Rochester cohort said that they hesitate “fairly often” or “very often” to express an opinion out of fear of their professors’ or classmates’ reaction. The situation is not unique to Rochester; it exists on many US college campuses and follows a national trend, the survey found.

David Primo, the Ani and Mark Gabrellian Professor and a professor of political science and of business administration at the University of Rochester, has made promoting free speech and expression a pedagogical priority—bringing guests from across the political spectrum to his classes and teaching an undergraduate course devoted to the topic, Disagreement in a Democratic Society. Primo also directs the Politics and Markets Project, an initiative he created in 2014 to encourage robust but civil discussions about contentious policy issues.

During a recent campus event, Primo urged universities to remain steadfast in their historical role as places of discussion and dissent. The “clash of ideas is the foundation for a college education. Without that you can’t have a well-functioning university,” he said. “Ideas that shape the world often emerge from college campuses.”

Fortunately, in the United States free speech is legally enshrined in the First Amendment to the US Constitution, and many private universities (which are not bound by the First Amendment in the same way as public universities are) have explicit commitments to support free speech and free inquiry on their campuses. “In other words, students have the right to speak freely, debate speech, and also protest against speech they don’t agree with,” Primo explained. “Of course, some universities do a better job than others of living up to these ideals.”

Even at universities that uphold the principles of free expression, problems arise, according to Primo, when faculty and students become unwilling to express their own ideas or challenge each other’s. Primo argues the fear of being professionally or socially ostracized is often on the minds of those with unorthodox or unpopular perspectives.

So, what happens when students think they can’t speak freely—to professors, administration, staff, or each other?

“A fear of speaking out means that important ideas may not be heard, important discoveries may not be made, and the boundaries of knowledge may not be pushed,” Primo said. “That kind of self-censorship can also extend to faculty members and influence the kind of research projects they pursue, or feel they ought to pursue. The acceptable range of ideas narrows more than it should.”

Read on for more highlights from Primo’s remarks.

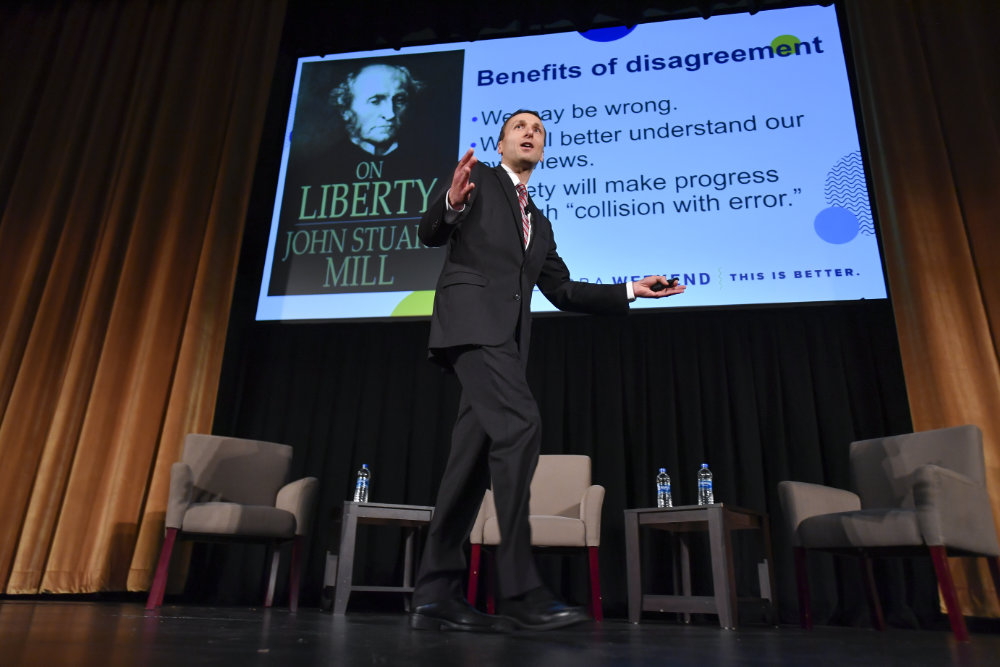

1. Heeding John Stuart Mill on the importance of ‘the heretics’

“You may say there are some people who just shouldn’t be able to speak—those crazy people on the left and those crazy people on the right. The 19th-century English philosopher John Stuart Mill had a name for these people—he’d call them the heretics, which was particularly appropriate given when he was writing, but I would argue is still appropriate now.”

Primo outlined three guiding principles on disagreement, distilled from Mill’s 1859 treatise, On Liberty:

- We should care about disagreement. We should interact with those we disagree with because we could be wrong. Otherwise we are assuming we’re infallible.

- You might understand your views on a contentious issue at a deeper level if you talk to someone who disagrees with you. It pushes you to understand your own ideas and positions better, and to learn to understand theirs.

- Society is going to make progress through error. That’s the hallmark of science: we have to be open to error and have ideas clash so that we can take the best parts of these ideas and move forward with knowledge generation.

2. On ‘affective polarization,’ or when politics became your identity

“When people’s political convictions become their identity—the blue team versus the red team—that’s what we political scientists call ‘affective polarization.’ Practically speaking, that means if I know that you’re a Democrat, I generally know much more about you than I would’ve known 30 years ago. Same if I know you’re a Republican. As a result, we’ve seen a rise in this idea that we don’t like somebody because they support the other party. In other words, it’s not just that we disagree with people on the other side; it’s that we actively dislike them as people because of their ideology or party affiliation.

“College students today are practicing affective polarization. In an NBC News poll a couple of months ago, nearly half of all college students said they wouldn’t room with somebody of a different political party. We ought to be figuring out exactly why that is—and how we can fix it.”

3. Responding to disinformation on social media

“There are serious issues with false information’s being transmitted on social media, but that’s something that we have to manage rather than regulate. Because if governments start limiting what can be said on social media, and if governments start regulating how social media companies moderate what’s allowed on their platforms, it becomes a slippery slope. Where then do you draw the line?

“When I think about restrictions on speech, I think about whether I would want those restrictions to exist when somebody I disagree with fundamentally is in a position of power. Because then they’re the ones who are going to control whether or not I can speak.”

4. Avoiding the ‘noise’ of MSNBC and Fox News

“Students need to cut through the noise and yelling on channels like MSNBC and Fox News and instead focus on having rigorous, courteous, civil debates. They should be shown why it’s important to care about the fact that we, as a society, are currently not disagreeing effectively.

“In class we have vigorous and valuable discussions, which signals to me that there’s a lot of support for the idea of open disagreement on college campuses. That’s why I am worried about the 27 percent of students who feel they can’t speak out. But I’m also heartened by the fact that we still have a tremendous number of students who are deeply engaged, who are willing to explore ideas. So, if we can help support them within the University then, that’s going to help because students are the ones who’ll be going out into society; they’re the ones who are going to be making the decisions and running the show in a few years. That’s why it’s vitally important they learn those skills here.”

5. Encouraging free speech among students—and supporting one another

“Students need to be supportive of each other as they explore ideas. On the first day of my seminar courses, I work with the students to set class norms and talk about the terms of debate in our class. One of the things we agreed upon this semester was that you can discuss outside of class what was said in class but not attribute specific ideas to specific people. I want students to be free to explore ideas without worrying that in two hours’ time what they just said in class would appear somewhere on social media. We want to have a truly safe space for the discussion of ideas without this fear. Of course, I can’t police whether students live up to these ideals. But I think the fact that students supported this ground rule shows that you can create this foundation to build up agreement to disagree on college campuses.

“When the heretics get to speak, I am reassured that we are protecting the right for all of us to express ourselves freely.”

Read more

‘Beyond blue lights’: Navigating trauma and triggers on college campuses

‘Beyond blue lights’: Navigating trauma and triggers on college campuses

A Rochester expert sheds light on the underrecognized challenges faced by college students recovering from trauma, and answers questions on the real meaning of trigger warnings.

Free speech and trigger warnings

Free speech and trigger warnings

On college campuses, where safe spaces and free inquiry often coexist, do trigger warnings protect students or hinder free speech? This episode of the University’s Quadcast podcast takes on the growing debate.

What’s the problem with civility?

What’s the problem with civility?

Three Rochester professors discuss the nature of America’s political and social divide and offer ideas on how higher education might help bridge the widening gap.