Twenty historic forts and castles extend along 500 kilometers of the Ghana coast, some crumbling ruins, others remarkably intact. Initially the forts and castles facilitated the gold trade; later they held enslaved people waiting to be shipped to the Americas. Over the centuries, they’ve changed hands from the Portuguese to the Dutch and British, and most recently to the Ghanaians.

They constitute a single world heritage site, protected by UNESCO as a “monument not only to the evils of the slave trade, but also to nearly four centuries of pre-colonial Afro-European commerce on the basis of equality.”

This is where University of Rochester students and faculty have conducted the Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School each of the last three summers. They have focused primarily on analyzing the architecture and materials of two of those structures—Elmina Castle, the oldest, built in 1482 but still largely intact, and Fort Amsterdam, the first English fort built on the Gold Coast in 1631, now badly deteriorated.

IN THE FIELD | Field school participants at Fort Amsterdam in 2018. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)

Digital Elmina

Michael Jarvis, working with Josh Romphf and Blair Tinker in the River Campus Library’s Digital Scholarship Lab, has created a website for the field school. Though still in progress, it includes:

- A breathtaking overhead pan of Elmina, taken from the drone in slow motion.

- An interactive GIS map showing how the Ghana coastal forts were built and then changed hands over five centuries.

Visit digitalelmina.org

The students use a drone, a laser scanner, and surveying tools to carefully document the dimensions of every room, vault, and courtyard. They use photogrammetry and CAD software to create detailed 3D models. And, when they return to Rochester, they apply finite element analysis to those digital models to better understand how the damage at Fort Amsterdam occurred, and how similar damage can be prevented at Elmina.

“You cannot study the healthy body if you don’t study the diseased body as well,” says Renato Perucchio, who launched the field school in collaboration with the University of Ghana and with permission from the Ghana Museum and Monuments Board (GMMB).

But the field school involves more than just taking measurements and creating models. Perucchio, a professor and chair of mechanical engineering and director of the Archaeology, Technology and Historical Structures (ATHS) program, designed the field school as an interdisciplinary endeavor—one that would also immerse students in the historical and cultural context of the structures they study.

Marcos dos Santos ’20 is a mechanical engineering major whose Brazilian ancestral roots extend to West Africa. He says participation in the field school the last two summers has allowed him “to speak to my past, to be connected to those in my ancestry—and to the ancestors of my friends—who suffered at the hands of others.”

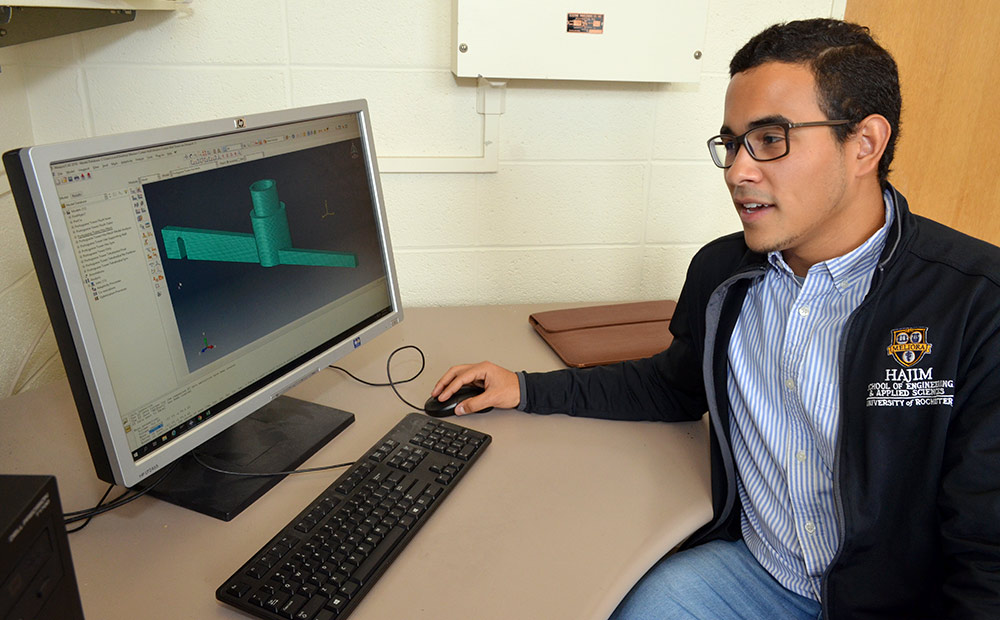

BACK IN THE LAB | Marcos dos Santos ’20 of mechanical engineering has participated in the field school each of the last two summers. He has been spending 7 to 10 hours each week this fall analyzing data gathered from the field school for a paper he is co-authoring with four other students. The software and modeling skills he has used during the field school will serve him well as he pursues a career in aeropace engineering, he says. He also appreciates the lessons he’s learned about the importance of working as part of a team to solve problems. (University of Rochester photo / Bob Marcotte)

Visiting a chief

Twenty-five students—six of whom returned a second year—have participated so far. Most are mechanical engineering and ATHS majors. However, students majoring in political science, digital media studies, and anthropology have also participated, including an art and art history major from the University of Michigan.

During their five weeks in Ghana, the students are kept busy not only with field work but a tightly packed schedule of lectures, guided trips to national parks and historical sites, and opportunities to meet with Ghanaians.

Gaia Saetermoe-Howard ’20, a dual ATHS and Eastman School of Music oboe performance major, says those conversations during the field school last summer gave her a deeper understanding of the legacy of colonialism in West Africa. Ghana was a British colony during much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

“I went with this very theoretical understanding about what colonialism feels like, or what these dynamics are actually going to look like in reality,” she says. “But when I got there, I realized it was a lot more complex than I thought it would be.”

HANDS ON | One of the trips during the field school last summer was to a bead factory. “I’ve learned in my archaeology classes about the cultural importance of beads in Akan society, but it was spectacular to view this process in person,” Gaia Saetermoe-Howard ’20 says. Wendi Heinzelman, dean of the Hajim School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, says the field school is an excellent example of a faculty-led program that offers undergraduates both hands-on research and a global experience that helps them understand a different culture. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)

Upcoming talks about the field school

Renato Perucchio, professor and chair of mechanical engineering, and director of the Archaeology, Technology, and Historical Structures program, will give two talks on the Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School, which he co-directs.

“Early Europeans in West Africa: Ghana’s Elmina Castle and Fort Amsterdam,” Nancy S. and Peter O. Brown Guest Lectureship in the Art and Architecture of Ancient Civilizations. 2 p.m. December 15, Memorial Art Gallery. Included in museum admission, free to AIA members. Learn more.

“Structural Engineering to the Rescue of Cultural Heritage,” Phelps Colloquium series. 4-5:30 p.m. February 26, 2020, Feldman Ballroom, Douglass Commons, River Campus. Register here.

Many of the students’ experiences have been chronicled in a blog.

For example, after attending an Akwasidae ceremony in a Ghanaian palace, the students were invited to visit a local chief. “We were all a bit nervous to be visiting the home of a chief,” wrote Naomi Rutagarama ’18, a political science major. The chief greeted the students warmly and at one point “stood in the center of the room to demonstrate the game-winning penalty kick he delivered at a college soccer game.”

The Rochester faculty who conduct the field school include co-director Perucchio, an expert in the engineering practices of classical antiquity who previously led a special University of Rochester summer program abroad on Roman Structures in Arezzo and Rome. He has studied structural damage and vault collapse at historical sites from Italy to Peru.

Chris Muir, also a professor of mechanical engineering, is a former principal engineer at Kodak and an expert in solid modeling of surveyed structures. He helps students, particularly those without an engineering background, learn enough about advanced surveying tools and modeling software to “take the shortest path to a solution.”

Michael Jarvis, an associate professor of history, previously directed an archaeology field school on Smith’s Island in Bermuda. He shares not only 30 years of archaeological experience, but also guides the students in the techniques of “digital capture from reality” using photogrammetry, laser scanning, and drone aerial footage. He is also the field school’s primary historian, providing insights into the slave trade, but also how Elmina functioned as a community and interacted with the town. “When students arrive, rather than just treat the castle as an inanimate object to study, I want them to understand the human dramas that played out there, from multiple perspectives,” he says.

Faculty from the University of Ghana’s Archaeology and Heritage Studies Program—including field school co-director Kodzo Gavua, William Gblerkpor, and David Abrampah—provide additional historical and cultural context.

Two summers ago, the project expanded when Christopher DeCorse, a professor of anthropology at Syracuse University, joined the team. He returned this past summer with two graduate students. DeCorse began his pioneering archaeological studies of Elmina in the mid 1980s, and later expanded his research all along the coast. His multiple books include An Archaeology of Elmina: Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast.

He also contributes local knowledge accumulated during more than 40 years of research in sub-Saharan Africa. So, when the Ghana Museum and Monuments Board made an urgent request, literally the day before the 2019 field school began, “we were there with exactly the appropriate technical expertise at the moment in which (the board) desperately needed it,” Perucchio says.

URGENT ARCHAEOLOGY | Fort Amsterdam, where field school participants carried out an engineering analysis this past summer at the request of the Ghana Museum and Monuments Board. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo / Samantha Turley)

‘A critical state of damage’

The request was for an engineering analysis of Fort Amsterdam, to be completed in four weeks. The analysis would help determine the feasibility of a proposal to redevelop the fort as a museum and as a school to train hospitality workers.

“Clearly this meant rearranging our program,” Perucchio says. “Our focus was turned 100 percent on Fort Amsterdam.”

First, the chief of the local village of Abandze was invited to the site. “We didn’t do any archaeological work until the chief, and the elders, and the traditional priest came by and poured libations,” Perucchio says. The chief’s representatives were regularly apprised of the work that followed.

Six trenches were dug to examine the fort’s foundations. Walls and vaults were visually inspected for evidence of fractures, which were then photographed.

The engineering and ATHS students, many doing archaeological digs for the first time, pitched in alongside DeCorse’s students. They were initially excited when it appeared that they were uncovering historic artifacts for the first time. Then a mechanical pencil was unearthed, and a piece of plastic. Some of the soil, it turns out, had been previously dug up and then replaced as part of restoration projects in the 1950s and, again, in the 1970s.

GETTING TO WORK | Field school participants lay out the units for archaeological digs at Fort Amsterdam this past summer. (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo / Christopher DeCorse)

Other University field schools

Six students participated last summer in the San Martino Archaeological Field School Torano di Borgorose, Italy. The program is designed to teach students about archaeological field and laboratory methods and the archaeology of ancient Italy. Led by Elizabeth Colantoni, associate professor of classic. Learn more here.

Four students participated in Project Fioretta: An Ethnographic Study of Disaster Recovery and Resilience in a Dolomite Village in Veneto, Italy, studying the aftermath of a severe storm that caused landslides and flooding in 2018. Led by Nancy Chin, associate professor of public health sciences and the Center for Community Health and Prevention.

Chin also leads a project in Ladakh, Kashmir, in the Himalayas, assessing mental stress in relation to climate change. Eight students have participated during the past two years. Contact Chin to learn more about both projects.

Contact Chin to learn more about both projects.

Nonetheless, some exciting discoveries were made in a trench dug on the fort’s north side, providing evidence of early English trade. “One of the coolest artifacts,” DeCorse says, was a European-made clay tobacco pipe stem— inserted into a locally made tobacco pipe bowl. “You often talk about cultural intersections and exchanges, but it’s rare that you get a single artifact that combines this entangled path,” DeCorse says.

Completing the report was “a gigantic effort,” Perucchio says. “But it moved us in a direction we had always wanted to go in, providing the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board with information it needed to have.”

The report concluded that “the existing masonry structures of Fort Amsterdam present an extensive—possibly critical—state of damage characterized by fractures, wall misalignments, and soil erosion.” This “clearly indicates the urgent necessity of a conservation process before any type of reconstruction can be considered.”

After completing work at Amsterdam, students shifted to Elmina to do additional archaeological digs—the first undertaken inside of Elmina castle—under Jarvis’ supervision.

One team, which included Jarvis, Saetermoe-Howard, and two other students, uncovered “a solid layer of 16th century ceramics, including Iberian glazed tiles,” Jarvis says. They were excavating in an out-of-the-way part of the castle that was “almost pitch black, so we had to rig up lights, which were hot, and it was already 90 degrees, so it was like being in a sauna, but we were finding amazing things.”

Despite the change in plans, this year’s field school achieved its goals, Perucchio says. “From the point of view of engineering we did everything we wanted to,” Perucchio says. “And from the point of archaeology we went way beyond anything that we had planned. “

An ongoing quest

This fall, students have been engaged in the next phase, analyzing the data they collected and testing the models they’ve created.

For her final ATHS project, Saetemoe-Howard will compare Elmina with three other Portuguese colonial forts in India, Kenya, and Brazil, which have been documented to varying degrees. She will try to connect the engineering of the forts, and the subsequent changes made to them, with the reasons they were built and the impact they had on the local people.

“I am trying with my project to not just blindly say ‘Let’s look at how beautiful this architecture is,’ because there’s this history [of European interference] that comes along with it.”

MODELING STRUCTURES | Gaia Saetermoe-Howard ‘20, a dual ATHS and Eastman School of Music oboe performance major, says her experience during the field school last summer gave her confidence using modeling software, which will be useful in finishing her ATHS final project. “I had never done any type of CAD (computer aided design) before I went to Ghana,” she says. “And I modeled at least 10 rooms, so that was amazing.” (University of Rochester photo / Bob Marcotte)

Dos Santos is coauthoring a paper with field school participants Louisa Anderson ‘20, Katherine Korslund ’20, Sabastian Abelezele ‘20, and Robert Cecil, ’20. They hope to present it at the next international Conference on Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions.

The paper will examine changes in the structural stability of the west curtain wall at Elmina resulting from modifications made over the centuries. It will also examine the possibility that a second defensive tower, in addition to one that still stands, was built by the Portuguese but later collapsed, perhaps during an earthquake in 1615.

Why does this matter? “The lessons we learn from one monument can help preserve other monuments,” dos Santos says. “And it’s important to be able to tell a more accurate story about Elmina’s past.”

“I think we’re pioneers in that regard, and I’m proud to be part of it.”

How do you bring a castle home with you?

Here’s a challenge: How do you convey a 91,000-square-foot castle with more than 160 rooms on the Ghana coast, back to Rochester, so at any time you could take a virtual tour as if you were really there? Or study the castle’s structure in such detail that every brick can be measured within 1-to-2mm accuracy?

Learn more >

Perucchio believes the work the field school is doing presents Ghana with an opportunity to link the coastal forts in a historically meaningful way that could bring more visitors to its coast.

Ultimately, however, that will likely hinge on convincing the Ghanaians themselves that these ancient forts can still have relevance for them, he says.

“For many of the Africans who live next to the monuments, and who, in one sense, should be much more interested in preserving them, the historical meaning of the monuments may be lost,” Perucchio says.

The most glaring example is Fort Nassau, which is now “buried under literally meters of modern debris,” Perucchio says.

“If we want to make sure that these monuments are preserved as world heritage sites, we need to address the fundamental question: whose heritage are we talking about?”

DeCorse, in the meantime, is eager to continue the participation of the Syracuse archaeology program—one of the best in the nation. The field school “is fascinating because it really does provide a unique interdisciplinary perspective,” DeCorse says.

He would like the same engineering and structural analysis being done at Elmina and Amsterdam to also be carried out at other forts and castles along the Ghana coast where DeCorse and his students have done archaeological surveys. This, he believes, will further the goal of providing the GMMB with the information it needs to “make informed decisions about how to manage” the structures.

“What is tremendously beautiful about this project it that it opens up one question after the other,” Perucchio says. “The students who really get the most out of this are those who engage in it as a continuing quest. This quest is not simply a quest in engineering or archaeology. It goes way beyond that. It’s connected with history, and it’s connected with real human lives.”

PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE | “I think about my friends, the long-lasting relationships that I’ve formed with the other participants,” Marcos dos Santos says when asked about his favorite takeaways from the field school. “We spent 15 to 16 hours every day working in Ghana and we have this bond. And I think we are going to carry it with us.” (Digital Heritage of West African Monuments Field School photo)