Capt. Norberto Nobrega ‘97S (MBA) feels “humbled” each morning when he reports to work in Morey Hall.

“I walk into the Victor Ohanesian Midshipmen Training Room and the Thomas King ’66 Wardroom,” says Nobrega, commanding officer of the University’s NROTC Unit, and a professor of naval science. “Both served their nation valiantly, with honor, and lost their lives in Vietnam.” He calls their legacies “enduring reminders” of the commitment and sacrifice made by men and women in uniform in service to the country.

Members of the University community have served in wartime since the Civil War, and many have paid the ultimate sacrifice. Ohanesian was an assistant professor of naval science at the University, and King was a distinguished student-athlete and battalion commander of the NROTC.

They are among those who gave their lives and are honored with plaques on the River Campus in Hirst Lounge at Wilson Commons and in the Veterans Memorial Grove in the Freshman Quadrangle: 10 in the Civil War, 11 in World War I, 57 in World War II, 4 in the Korean War, and 17 in the Vietnam War.

Nobrega says his office knows of no alumni who died in the Persian Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, or the Iraq War.

As Memorial Day approaches, we profile five University community members who gave their lives during military service.

(University photos / River Campus Libraries; Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

Civil War

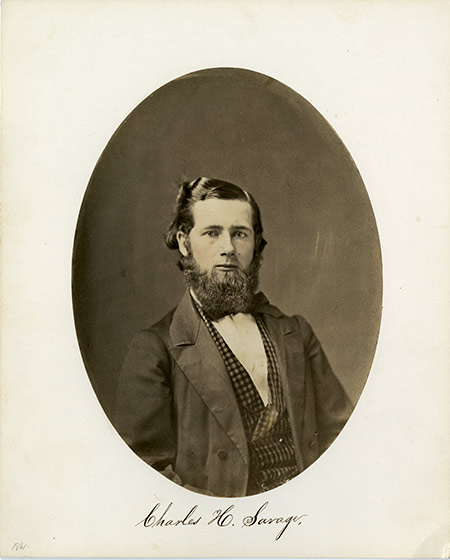

Charles Savage, Class of 1861

University president Martin Brewer Anderson had been a voice of moderation in the months leading up to the Civil War. But when Confederate forces fired upon the North at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861, he urged military action to suppress the rebellion.

One of the first students to respond was Charles Savage, Class of 1861, who enlisted in the Union army just 18 days after the attack.

The Rochester native had been active at the University as a member of the Anti-Secret Society (now Psi Upsilon), the chess club, and gymnasium. He joined the 13th Regiment of New York State Volunteers, while University professor Isaac Quinby, a West Point graduate who had served in the Mexican-American War, was appointed colonel of the regiment.

Savage rose to captain before he lost his life at Second Bull Run on August 30, 1862. Union general John Pope ordered the 13th and other Union regiments to attack Stonewall Jackson’s soldiers, who were dug in along an unfinished railroad cut in Manassas, Virginia. The Union regiments had to attack across 600 yards of open field, facing a relentless crossfire from Jackson’s riflemen in front of them, and from Gen. James Longstreet’s artillery to the left.

Nearly half of the 240 men in the 13th were killed or wounded. According to a report in a Rochester daily newspaper, the Daily Democrat, witnesses said Savage reeled toward Union colonel Elisha Marshall in terrible pain from a bowel wound. Marshall placed him behind a large rock, with a canteen at his side, but Savage died 20 minutes later. He was 26.

World War I

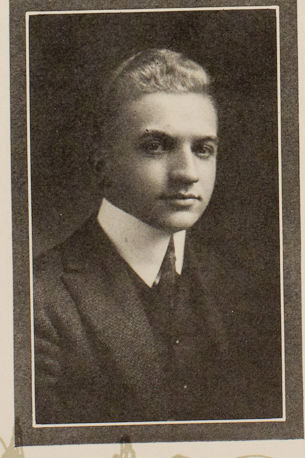

Lawrence Atkins, Class of 1915

Atkins grew up in Holley, New York, 25 miles west of Rochester, enrolling at the University in 1911. He became student body president, was a member of the track and baseball teams, and served as “assistant cheer leader.”

He was a gregarious student, as his yearbook profile details:

With thoughts of girls, his fair blond head

We know is filled quite full;

Yet even more than girls ‘tis said,

He loves to shoot the bull.

After graduation, Atkins was one of 10 Holley youths to join the 106th Ambulance Company. When the National Guard was called out in 1916 during the Mexican Revolution, Atkins’s company headed to the Mexican border. The following year, he was promoted to corporal, then sergeant. And in June 1918, with the First World War still raging, his company was sent to France.

By that fall, peace was on the horizon. But so, too, was a vicious influenza pandemic that would infect one-fifth of the world’s population and kill an estimated 30 million people. As the virus struck military camps and trenches, Atkins was among the approximate 45,000 American soldiers who succumbed to the illness. He died on October 30, 1918, in a hospital in France just 12 days before the official end of World War I.

World War II

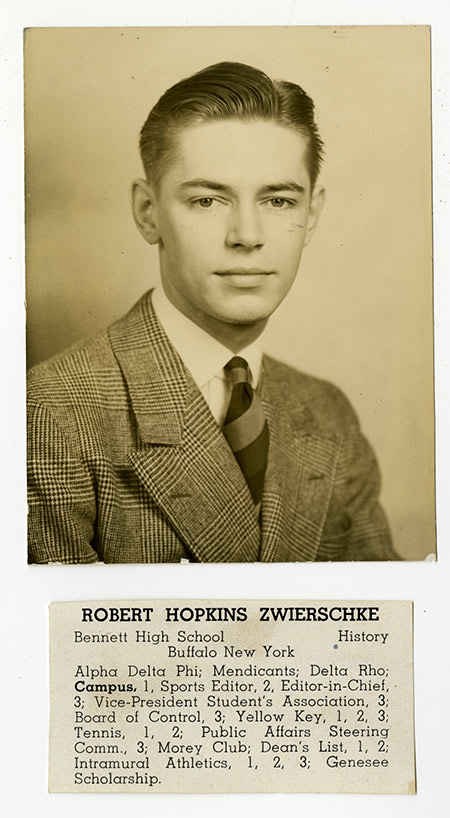

Robert Zwierschke ’39

On his application for admission to the University, Robert Zwierschke listed “law, teaching, and research” as his subjects of interest.

“My life, for the most part, has been very happy and carefree,” the Buffalo native wrote in his essay. “I’m an average boy from an average home. When I have graduated from the University and have attained my desired degree, I sincerely hope to enter upon a serviceable and successful life.”

Zwierschke majored in history, lost a close race for Students’ Association president, and became editor of the Campus Times. As a senior in 1939, he echoed the isolationist mood of much of the country when he wrote in an editorial, “Young men have no burning desire to act as receivers for machine-gun fire.”

However, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed many attitudes. The United States declared war on Japan, and six months later, Zwierschke was dead—the first University alumnus to die in World War II.

He served as an ensign on the aircraft carrier USS Lexington and was killed during the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 7, 1942, when the Lexington was torpedoed and sunk by the Japanese navy. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

Korean War

Spiro J. Peters ’50

Spiro Peters grew up in Rochester and served three years in the Air Force during World War II as a navigator and radar specialist. In September 1946, he enrolled at the University, eager to build a career.

“After the unsteady and irregular life spent in the Army, I’m ready to take advantage of the many opportunities offered by schooling at Rochester,” he wrote on his entrance essay.

Peters spent three years at the University before he was called back to the Air Force Reserves to serve in the Korean War. In August 1952, he was assigned to the 371st Squadron of the 307th Bomb Group in Okinawa as a navigator and radar specialist on B-29s.

Peters already had flown a mission when, on September 13, 1952, an inexperienced pilot, who had been in Korea for only a week, asked him to join another. Their target was a hydroelectric power plant complex, but as their B-29 approached the plant, it came under heavy anti-aircraft fire from the ground. According to a report in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, eyewitnesses described the plane exploding in mid-air, while others saw parachutes deployed.

Was Peters dead? Injured? Captured? No one knew for sure, and he was listed as missing in action.

A year after the plane went down, his wife, Anne, received a telegram from the Defense Department stating that it had “unofficial and unconfirmed” reports that Spiro might be one of 944 Americans unaccounted for in North Korean prison camps. She called it “wonderful news,” but sadly, it wasn’t true. On February 28, 1954, 17 months after his plane went down, Lt. Peters was presumed dead. His remains were never found.

Vietnam War

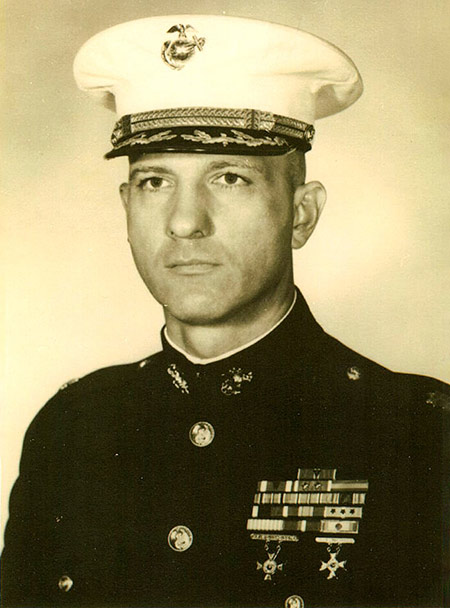

Victor Ohanesian

Assistant Professor of Naval Science, 1962–64

Victor Ohanesian, a Pennsylvania native, had enlisted in the Marine Corps in September 1944 and saw active duty in World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and was awarded three Purple Hearts for injuries sustained in Korea.

His dedication was honored in 1954 when, as President Eisenhower’s military escort, he laid a wreath at Lincoln’s Tomb in Springfield, Illinois.

A career military serviceman, when the first of his three daughters was born in 1956, he came home to meet her a week later, then didn’t see her again until she was 14 months old.

With two wars behind him, Ohanesian joined the University in 1962 and taught Naval Reserve officer candidates for three years. He was one of the first in Rochester to heed President John F. Kennedy’s call to march 50 miles in less than 20 hours as a show of physical fitness. Ohanesian finished in 18 hours.

He was recalled to duty in Vietnam in June 1966. The commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, he was fatally wounded by mortar fire on February 28, 1967, while rescuing a fellow marine near the demilitarized zone. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Cpl. T.J. Croft, who served with Ohanesian in Vietnam, wrote on a veteran’s website a few years ago, “Have you ever met a Marine Corps officer who you had so much respect for that you’d literally follow him to hell and back? Colonel Ohanesian was such a Marine.”

In October 2014, the University named its midshipmen training room in honor of Ohanesian.