Speakers of a language rely on its words to carry out even the most mundane acts of communication. But the same words are poets’ medium of creation.

How do poets turn bare utterance into art?

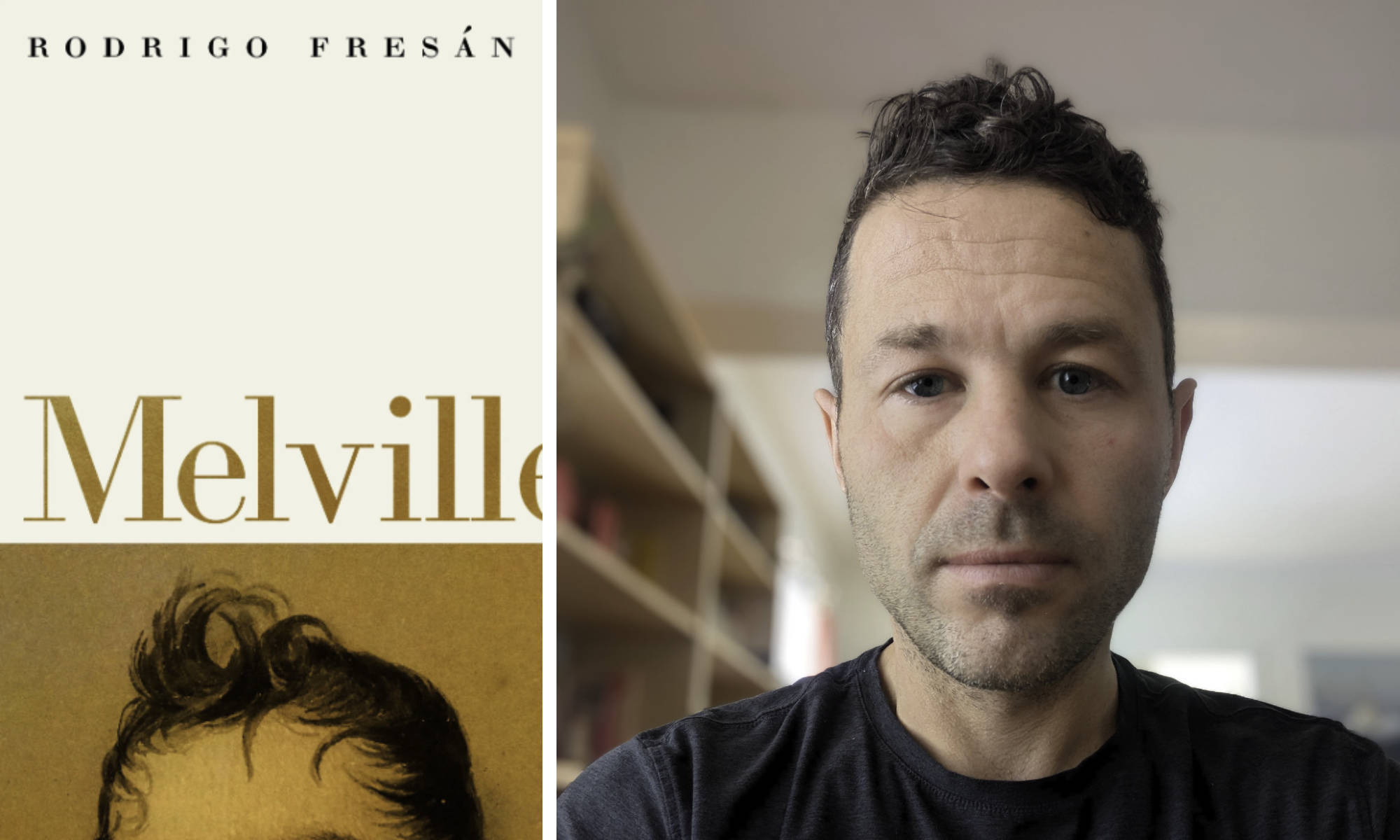

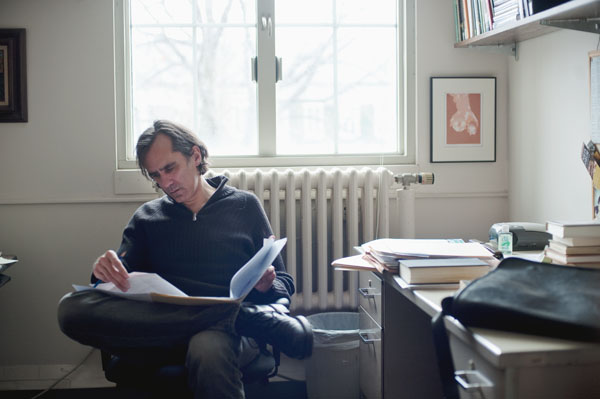

James Longenbach, the Joseph Henry Gilmore Professor of English at Rochester, offers an answer with his newest book, How Poems Get Made (W. W. Norton, 2018). It grows out of his decades of teaching poetry. “I was pushing myself to find a way to describe how we work with the most basic elements of the poem,” he says.

“The sonic nature of the language—the way that you’re seduced into a web of patterns that has to do with like and unlike sounds, that has to do with the stress of syllables, that has to do with the length of the sentences, that has to do with the length of the lines and the ways they introduce tensions into the lengths of the sentences—all those things are pacing your experience of the poem and giving momentum and release to your experience of the poem,” he says. “And that’s all taking place on the level of sound.”

A singular focus on the sonic quality of language sets poetry apart from all other forms of writing. It’s what makes poems a form of literature that people are especially apt to listen to, or read, again and again—and again.

“You might want to read a parking ticket a second time, but I doubt you’d do it for pleasure,” says Longenbach. “The language, rightfully in that situation, isn’t trying to bring attention to itself in a way that’s creating sonic patterns within the sentences, within the words, within the syllables, that are giving you a tactile or a sensory feeling that in turn gives you pleasure. A poem, one way or another, has to do that, or else there’s no reason for it to be a poem.”

Poems aren’t simply vehicles for conveying information; they’re sonic and temporal events. Longenbach writes that “we savor our experience of the poem’s language as it unfolds in time, luring us forward.”

The sounds of English

Longenbach draws on examples stretching from Old English poet Cædmon to poets of the Renaissance and Romantic eras, and on to modern and contemporary poets. His book is explicitly about poetry in English. At its root a Germanic language, English was reshaped with the Norman invasion of England in the 11th century, when the French language became the tongue of the English royal court. Today, more than 70 percent of words in English come from non-Germanic sources. Modern English pivots endlessly between Germanic and Latinate words; “often we feel we’re grappling with more than one language at once, as if the act of writing in English were already an act of translation,” Longenbach suggests.

Germanic English words can seem plain, and even vulgar; words from Latin might sound authoritative or captivating. “We all hear the difference, even if only subconsciously,” he says. “Things like that are revealed in every sentence you speak. Even in the sentence I just uttered. Things like that are—all those grungy little German words. Then I leapt to a Latinate French word: revealed.” But a poet’s skill can upend such associations, Longenbach notes, juxtaposing words to make even “the bluntest monosyllables seem magical.”

English’s complex history underpins the first of the poetic building blocks he names: diction, or word choice. He identifies the other fundamental tools as syntax, or the arrangement of words; figure, or metaphor; and rhythm, the pattern of stressed syllables forged by choices in diction and syntax. The interplay of these components creates a “sonic drama” that is performed from the level of a single line to that of an entire poem.

The thrill of the plunge

Emily Dickinson once wrote about a fellow poet, whose name has been lost: “Did you ever read one of her Poems backward because the plunge from the front overturned you? I sometimes (often have, many times) have—A something overtakes the Mind.”

The “plunge” she describes is “the temporal process of getting from the beginning to the end of the poem,” Longenbach says. Moving the poem’s reader or listener through the time of the poem, gaining the momentum of inevitability that gives readers the thrill of a plunge, is the work of the poet’s sonic choices. Throughout How Poems Get Made, he joins Dickinson in her experiment of reordering a poem’s lines to find how drama builds.

“Just getting the words down on the page—that’s like a painter squeezing out the paint on the palette. Now you’ve got something to work with, when you’ve got the words on the page,” says Longenbach, the author of 13 books of and about poetry and a poetic contributor to such publications as The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The New Republic. “And working with it often means moving them around. Changing the order. What happens if I put this first? What happens if I take what I wrote first and put it last? And that can be wonderfully revelatory and very exciting for students when they see the huge effect that comes from what might seem like to them, at first, doing almost nothing.”

Getting to the heart of poetry

But what can strike students as a small editorial gesture in fact goes to the heart of what poetry is. Through its simultaneous acts of echo, diction, figuration, syntax, and rhythm, a poem forges a “repeatable path of discovery” and a “new knowledge of reality.” It’s a kind of understanding that Longenbach labels “lyric knowledge.” It’s not an information-based form of knowledge; it’s an enchantment by “the movement of the medium,” a pleasure that’s infinitely repeatable, growing richer with time.

It might sound mysterious, but Longenbach points out to his students that they revel in sound and repetition when they listen to pop songs.

“They’ve got the song completely memorized in their head and yet they listen to it over and over again. It’s not because they’ve forgotten the song. It’s because they like how it feels to do it again.”

Read more

April is National Poetry Month, established in 1996 by the Academy of American Poets to celebrate the art of poetry.

Students celebrate World Poetry Day with on-air readings

Students and tutors from the University of Rochester’s Language Center were on local radio this week to mark World Poetry Day with a celebration of poems in Arabic, Korean, Portuguese, and American Sign Language.

Poetry a ‘powerful catalyst for dialogue and peace’

In honor of World Poetry Day, University of Rochester students at the Language Center share some favorite poems in the languages in which they were written.

Poetry in the age of the tweet

The pace of digital life has only quickened over the last twelve years since Twitter was founded, but the slower process of reading and crafting poetry continues, robustly, at Rochester.