The only instrument of its kind in North America, the full-sized Italian baroque organ at the Memorial Art Gallery is a musical time capsule.

“This organ is like a living recording of the 18th century,” says David Higgs, an organ professor with the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and one of the country’s leading concert organists, of the full-sized Italian baroque organ in the Memorial Art Gallery.

The organ was rescued in 1979 from an antique gallery in Florence, where it likely would have been sold as furniture. After being fully restored in Germany, it was purchased by the Eastman School and installed in the Memorial Art Gallery’s Fountain Court in the fall of 2005, making Rochester the only place in North America to hear authentic performances of 18th-century organ music written for a large Italian instrument. In addition to enhancing organ study at the Eastman School, the organ benefits the singers and instrumentalists who perform with the instrument, visiting scholars, practitioners of organ restoration, and visitors to the Memorial Art Gallery.

The organ is an ancient instrument whose “golden age” was the 17th and 18th centuries, when Italy was at the center of the musical world, says Honey Meconi, professor of musicology in the College Department of Music.

How does the Italian baroque organ work?

How does the Italian baroque organ work?

The wind bellows operator or calcant (1) depresses the pedals with his feet, forcing a column of compressed air through the wind trunk (2) to the wind chest (3), an airtight wooden box below the pipes in the organ case.

Each row of pipes (4), or rank, representing a particular tone quality, is controlled by a stop knob (5).

When the organist pulls the knob, a mechanical link moves a wooden slat or slider (6) beneath the pipes.

Holes in the slider are lined up with the pipes, allowing them to be played.

The organist presses a key (7) and a wooden panel or pallet (8) opens, allowing the pressurized air in the wind chest to flow into the key channel (9). Now the rank of pipes connected to that channel will sound or speak.

Fountain Court

Now home to the baroque organ, this room at the museum–designed in 1926–has architectural proportions similar to those of a small Italian Renaissance church, says Higgs, which adds to the preservation of authentic 18th-century sound. The organ is surrounded by more than 30 major baroque paintings and sculptures from the gallery’s permanent collection.

Bellows

An organ’s bellows are “the lungs of the instrument,” says Higgs. These bellows, located in a small room adjacent to the Fountain Court, probably predate the 18th century. They provide air through the wind trunk to the wind chest, which supplies the air to sound the pipes. An electric blower is used to operate the bellows for rehearsals, but for most public performances—which occur regularly, including every Sunday—a person, called a calcant, operates the bellows by foot. “It gives more liveliness to the sound,” Higgs says.

Console

The keyboard, pedals, and stop knobs—which open and close various sets of pipes—form the console. The combination of stops, pipes, keys, and pedals allow the organ to produce a wide range of sounds. “It’s like an orchestra in one instrument,” says Meconi. Performers’ fingers from over the centuries have worn indentations into the organ’s keys that manifest the tight connection between the player and the organ. “The instrument tells you what you have to do,” says Edoardo Bellotti, an associate professor of organ, harpsichord, and improvisation, likening it to a living thing.

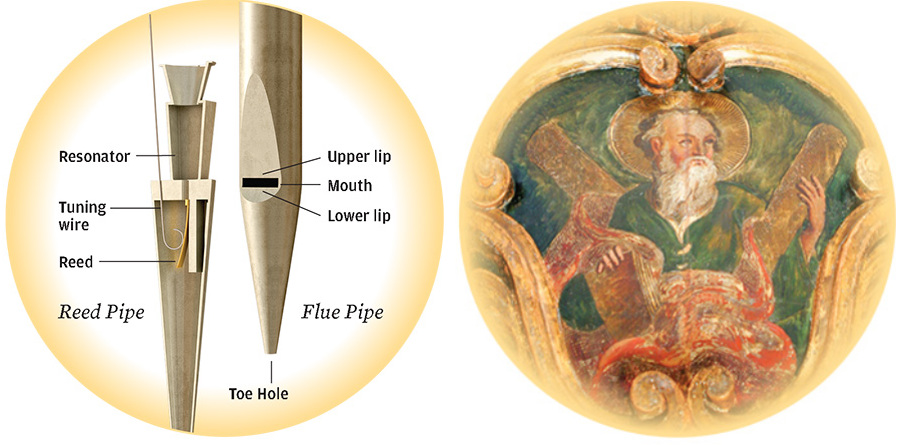

Pipes

The organ has almost 600 pipes made of tin and lead alloy and wood, which range from the size of a pencil to more than six feet in height. Some of the pipes, like the wind chest, date from circa 1670. “Impurity in the metal pipes is one ofthe secrets” of each pre-modern organ’s unique sound, says Bellotti.

Hand crafted

The lavishly decorated, wooden organ case features carved ornamentation, classically inspired painted vases, and an elaborate gilded crown ornament depicting Saint Andrew, perhaps a reference to the patron saint of the unknown church or chapel where the organ was first located. The case probably dates from between 1730 and 1770, when the original instrument—from around 1670—was enlarged and reinstalled in the new case, likely built to match the ornamentation of its surroundings.

Read more

Memorial Art Gallery collections add new dimension to Renaissance Impressions

Memorial Art Gallery collections add new dimension to Renaissance Impressions

A new exhibit pairs decorative arts objects with prints from the renowned Kirk Edward Long collection of Renaissance prints.

Nearing its eighth decade, a modern musical invention remains cutting edge

Nearing its eighth decade, a modern musical invention remains cutting edge

When the Eastman Wind Ensemble was founded at the Eastman School of Music in 1952, it launched a movement in wind music.

Play a Bach duet with an AI counterpoint

Play a Bach duet with an AI counterpoint

BachDuet, developed by University of Rochester researchers, allows users to improvise duets with an artificial intelligence partner.