The Rochester professor emeritus and new American Astronomical Society fellow now explores the brain’s waste disposal system.

John (“Jack”) Thomas officially retired in 2014, but the honors keep coming.

The professor emeritus of astronomy at the University of Rochester was recently recognized as a fellow of the American Astronomical Society (AAS). The society, which has existed since 1899, began recognizing fellows three years ago. The AAS is honoring Thomas not only for his service and leadership, but also for five decades of groundbreaking contributions to solar and stellar physics, “including advancements in our understanding of the behavior of magnetic fields and theoretical and observational studies of sunspots.”

Not content to rest on his laurels, Thomas, now 80, has started a new chapter in his illustrious career. Lured from retirement, he is pursuing an altogether different but equally groundbreaking area of research.

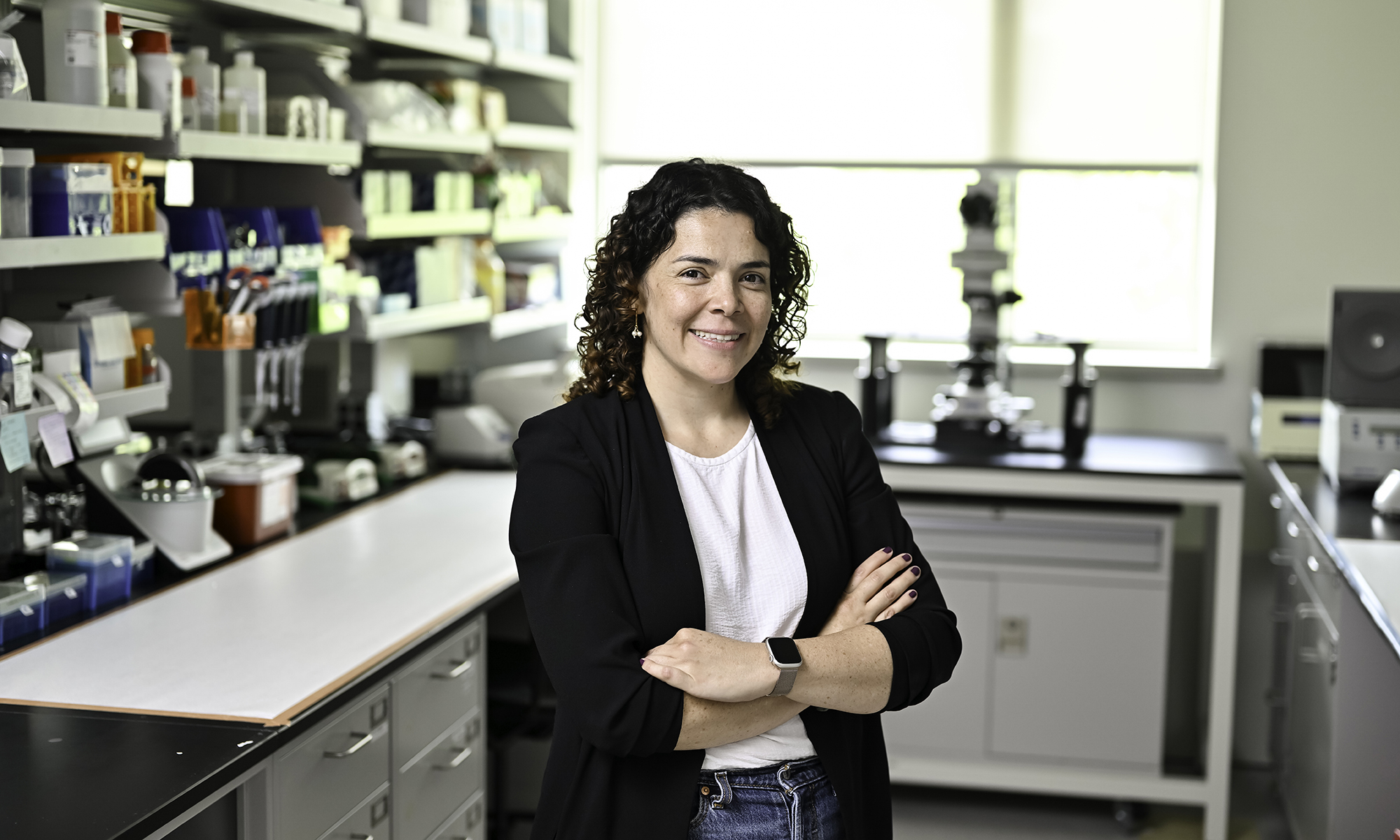

Thomas, who is also professor emeritus of mechanical and aerospace sciences, is helping Maiken Nedergaard, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at the University’s Medical Center, expand on her breakthrough discoveries about the brain’s glymphatic system. The system, which comprises a plumbing network that piggybacks on the brain’s blood vessels and pumps cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) through the brain’s tissue, flushes away waste.

The collaboration also involves two of Thomas’s colleagues in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, associate professor Doug Kelley and assistant professor Jessica Shang.

“This whole thing has been absolutely amazing,” says Thomas. “I have been reborn as a neuroscientist. I am learning so many things about biology that I never knew about. It’s just been wonderful.”

Ever-expanding collaborations yielded solar discoveries

Thomas was interested in astronomy as a child, looking at stars and planets through a small telescope with his father.

However, his interest in astrophysics was sparked during his doctoral work on magnetohydrodynamic turbulence at Purdue University and a subsequent NATO postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Cambridge from 1966 to 1967.

After joining what was then called the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Sciences at Rochester, Thomas began collaborating on theoretical modeling of fluid flows on the sun with Alfred Clark, professor of mechanical engineering, of mathematics, and, later, of biomedical engineering.

Over the years, Thomas’s collaborations expanded to include colleagues in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Rochester, including Hugh Van Horn, Adam Frank, and Eric Blackman. He also worked with researchers at the National Solar Observatory in New Mexico, the High Altitude Observatory in Boulder, Colorado, and the Laboratory for Space Astrophysics and Fundamental Physics in Madrid, among other institutions.

Thomas’s main research focus was the sun’s magnetic field and how it gives rise to sunspots on the sun’s surface. He modeled the structure and dynamics of sunspots, including the motion of waves across them and the flow of material inside. In the early 1980s, Thomas originated the concept of probing beneath sunspots by observing acoustic oscillations—essentially “sunspot seismology”—to gain previously unknown information about the sunspots’ structure.

“I’m very proud of the work I did with my colleague Nigel Weiss (University of Cambridge),” Thomas says. “He and I wrote a book together for Cambridge Press called Sunspots and Starspots, published in 2008. A lot of the work we did is described there.” Thomas spent sabbatical years at Cambridge and Oxford in England, and he is a life member of Clare Hall, Cambridge, and Worcester College, Oxford.

In 1993, Thomas received a Guggenheim Fellowship for his research on solar and stellar magnetic fields.

He was elected a fellow of the American Physical Society in 2000 for “major contributions to solar magnetohydrodynamics.” And in 2007, Thomas was named a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science for elucidating the physics of the sun and other stars, and for his broader contributions to the solar community. Most notably, Thomas served for 10 years as scientific editor of The Astrophysical Journal, the foremost journal in the field. He also chaired the Solar Physics Division of the American Astronomical Society from 1995 to 1997.

At Rochester, Thomas served as an associate dean for graduate studies in the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences (now the Hajim School of Engineering & Applied Sciences) and then as the University Dean of Graduate Studies for eight years.

All of this would be more than enough to constitute a remarkable career.

But then in late 2016—two years after he retired—Thomas received an email from Maiken Nedergaard.

Cancer diagnosis spurs return to research

A rapid series of discoveries from Nedergaard’s lab four years earlier showed that the brain has its own unique waste removal system. Moreover, this glymphatic system is primarily active while we sleep. The latter discovery was selected by Science magazine as one of 2015’s top 10 “breakthrough” scientific achievements.

Nedergaard asked Thomas to help her research group better understand the microfluidics involved in this glymphatic cleansing system. He agreed, and immediately contacted his colleague, Douglas Kelley, whose research group had already developed algorithms to track particle flows in fluids. The algorithms could be readily applied to Nedergaard’s study.

Thomas says there were two motivations for him to come out of retirement.

“The fluid dynamics interested me,” he says. Yet there was a strong personal motivation as well: his wife had been diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive cancer that they both knew to be incurable. The glymphatic system offers possible pathways for getting drugs to the brain, and perhaps eventually providing better treatment for future patients with glioblastoma and other brain diseases, Thomas says.

“My wife was very pleased to see me possibly getting back into research, that I would have this to keep me busy in retirement,” Thomas says. “And she was right on the mark. It was really a big help in dealing with her loss.”

Since the collaboration with Nedergaard started in early 2017, Thomas has worked with Kelley on seven published papers and two more currently under review, and with Nedergaard on several other published papers. He has also published a single-author paper on brain fluids and recently submitted another.

In retrospect, Thomas is surprised that Nedergaard contacted him, “because I had done things on this huge astrophysical scale, at kind of the opposite extreme of the work she is doing.”

Kelley is glad that she did.

Thomas is “highly productive and tremendously generous with his time,” Kelley says. “He attends biweekly meetings with our research teams. His insights are a tremendous help to students, postdocs, and faculty alike. With so much experience, his instincts for solving scientific puzzles and interpersonal challenges are just excellent. It’s an honor to have him as a mentor and colleague.

“Jack is unarguably a leader in the field.”

The perks of academia: ‘opportunities to just keep learning’

Thomas says his career has been a testament to the unique opportunities that academia offers to pursue “a lifetime of learning.”

Many of the courses he taught fell outside his primary research area, requiring him to continually refresh and update his knowledge of basic subjects, such as fluid dynamics, plasma physics, and thermodynamics. “There’s a joke among professors that if you want to learn a subject, volunteer to teach it, because then you’re forced to learn it. But to me that was just a delight,” Thomas says.

Thomas’s own undergraduate degree at Purdue was in engineering sciences.

“So, basically I was an applied mathematician,” he says. “But then I started doing astrophysics. I had to learn about that field, and then geophysics. I later did some research on lake circulation in Lake Ontario, some oceanography, worked on convection in the earth’s mantle, and then broader aspects of solar and stellar physics. And now I’m learning brain anatomy, and all sorts of things,” Thomas says.

“That’s what comes with the academic life. There are always opportunities to just keep learning.”

Read more about our people

Harvey Alter’s Nobel Prize honors a half-century quest

Harvey Alter’s Nobel Prize honors a half-century quest

The Nobel laureate’s work as an NIH hematologist led to profound improvements in blood transfusion safety and starkly reduced transmission of a potentially deadly virus.

Beth Greenwood ’22 in a league of her own

Beth Greenwood ’22 in a league of her own

The mechanical engineering major continues to break boundaries for women in baseball. She’s played for Rochester’s varsity team, trains with the US national women’s squad, and will appear in an upcoming TV show on Amazon Prime.

Northwestern University dean named provost at Rochester

Northwestern University dean named provost at Rochester

David Figlio—whose research and academic leadership cuts across economics, education, and social policy—will become Rochester’s chief academic officer in July.