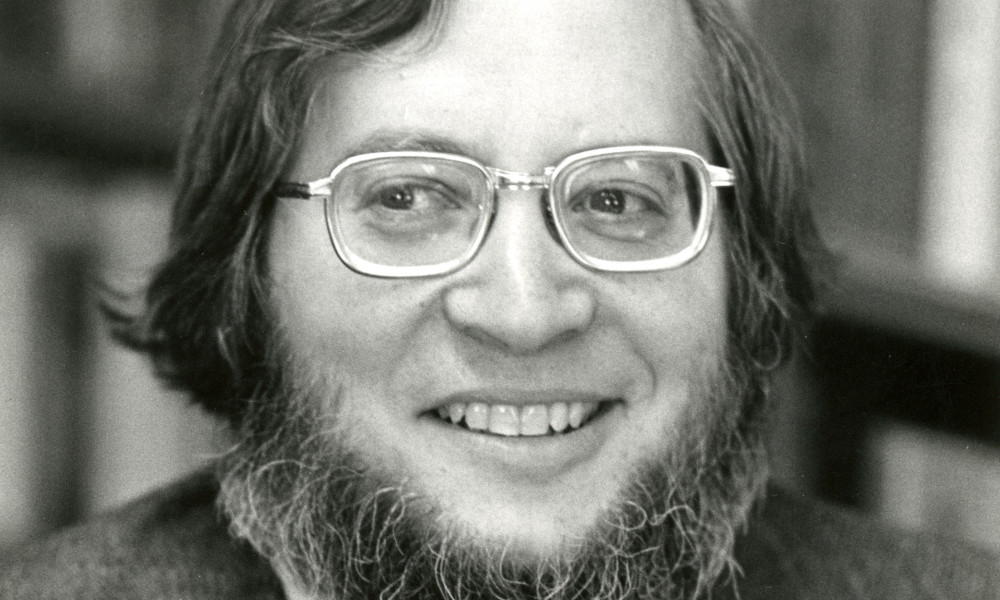

Stewart Weaver Surveys Exploration Through the Ages

What is exploration, and what distinguishes it from travel, discovery, or adventure?

Stewart Weaver’s survey of the history of exploration, slated for publication by Oxford University Press in December, offers a compelling set of answers.

In 160 succinct pages, Exploration: A Very Short Introduction chronicles journeys of discovery from the pre-history trek of humans across the land bridge over the Bering Strait some 12,000 years ago to the mid-20th century deep sea voyages of Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Along the way, Weaver identifies what defines exploration during each era and places these historic achievements in the largest possible global context: that of the natural history of the earth itself.

An avid hiker and coauthor with Maurice Isserman of Fallen Giants, an award-winning history of Himalayan mountaineering, Weaver gives as much credit to those who climb mountains and don scuba gear as to the first people to set out across the open ocean. “A true explorer,” writes the professor of history at the University of Rochester, “is a traveler who seeks a discovery.” Through brief accounts and assessments of their missions, Weaver captures the adventure, the wonder, and the legacy of these feats.

Exploration typically grows out of the cultural exchange of goods and ideas when two populations meet, explains Weaver. Native peoples, who often served as unsung guides, are essential to success. According to Weaver, these individuals embody “what exploration is often fundamentally about: mediation, intercession, cultural negotiation and sometimes, even, symbiosis.”

Weaver includes famous explorations, from the Lewis and Clark expedition to the first moon landing. But the slim volume—part of Oxford University Press’s well-known “very short introductions” series—also makes room for lesser-known undertakings, like the numerous attempts to reach the South Pole and the rivalry and glory seeking that ensued among countries and individuals during those early 20th century efforts to set a new “farthest south.”

Throughout, Weaver reviews the scholarly and popular debates that have turned men like Christopher Columbus from among the most celebrated to the “now much-denigrated.” Columbus, writes Weaver, “may have been more persistent than most explorer-adventurers of his age; he may have been unusually adroit when it came to the all-important art of securing royal patronage. But he was far from being either the lone visionary or the arch villain of competing classroom mythologies.”

Taken together, the millenia-long record of travel provides a reminder of the extreme hardships involved in venturing into the unknown. For example, during the numerous 19th century attempts to find the fabled Northwest Passage through the Canadian Artic, John Franklin’s ship became stuck in the ice, condemning the expedition’s 24 officers and 105 men to a slow death from scurvy, starvation, and botulism. The conditions the crew and others like them endured as they “over-wintered, sick and starving, in these dark and frozen wastes defy description,” writes Weaver.

So what drives humans to such lengths? For Weaver, the answer lies in human nature. “For all the different forms it takes in different historical periods, for all the worthy and unworthy motives that lie behind it, exploration—travel for the sake of discovery and adventure—is it seems a human compulsion, a human obsession even (as the paleontologist Maeve Leakey says); it is a defining element of a distinctly human identity, and it will never rest at any frontier, whether terrestrial or extra-terrestrial.”