MAG’s decorative arts underscore central themes in a traveling exhibit of master prints from the Kirk Edward Long Collection.

Round the first corner of the Renaissance Impressions exhibit now on display at the University of Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery, and you’ll notice an array of magnifying glasses suspended on wall hooks.

“I put these in all my print shows,” says Nancy Norwood, the museum’s curator of European art. “If people can’t see it, they’re not going to get it.”

There’s a lot to see—and to get.

The 82 etchings, engravings, and woodcuts in the exhibit organized by the American Federation of the Arts are selections from the Kirk Edward Long collection. The Long collection is one of the most comprehensive and highly regarded collections of Renaissance prints in private hands in the world. The scenes the prints depict—allegorical, Biblical, and Classical—are rich in detail.

Reflecting Long’s interests, they contain tell-tale features of the Late Renaissance style known as mannerism. Bodies are crammed together, in tangles of torsos and limbs. Nudity abounds, with anatomical features carefully, but not necessarily accurately, rendered. There are muscular babies, and fully developed human forms with animal ears, noses, legs, and genitalia. Faces are frozen in expressions of ecstasy, pain, horror, and bliss.

Peer closely, and you see how all this complexity, shadow, and depth are achieved with nothing more than individual, discrete black lines.

“I’m amazed by printmaking at this period in particular,” says Norwood, pausing at a large engraving by the German artist George Pencz (c. 1500–1550). The print, The Taking of Cartagena, extends nearly two feet wide and a foot-and-a-half tall. Norwood notes the depth of the image, from the battle in the foreground to the distant countryside. “Just imagine, a piece of metal and a pointy object,” she says, referring to the steel tool used to make grooves in copper plates. “And from that, you get this.”

An Asian invention transforms the European continent

Taken together, the prints tell a story of sweeping change. It’s not hard in our own time and place to recall moments when novel objects and images seemed to come out of nowhere and were soon found everywhere. To live in Europe in the 16th century was to experience exactly that with the arrival and spread of prints.

Printing flourished in China and Japan for several centuries before the practice took hold in Europe. It’s thought that printmaking—and its essential component, paper—arrived in Europe through travel and trade. As paper mills sprouted up across the continent in the 15th century, a new art form arose that changed not only the practice and business of art making and consumption, but material culture throughout much of Europe.

Prints led to a shared “visual vocabulary” across much of Europe, Norwood explains. To be educated in the popular sense meant to recognize certain figures and scenes that commonly appeared in prints. And over time, to understand the meanings ascribed to them.

It’s easy to forget that, prior to printmaking, the only way to access visual depictions of Greek gods or goddesses, or of Biblical figures and stories, was to stand before singular, original, one-of-a-kind works of art. Those works were clustered in present-day Italy. Artists engaged in printmaking traveled to these “sources” and were able to disseminate their replications or interpretations of Classical and Biblical imagery throughout the continent.

MAG’s decorative arts show dissemination, influence of printed images

The MAG exhibit excels in conveying just how wide the reach of these images became. In an unusual move, Norwood suggested to the AFA that MAG would incorporate into its display items from the museum’s permanent collections in order to underscore this key takeaway.

“I have a great collection to work with,” says Norwood, who has been in her role at MAG for 21 years. Incorporating decorative arts objects was “a no-brainer.”

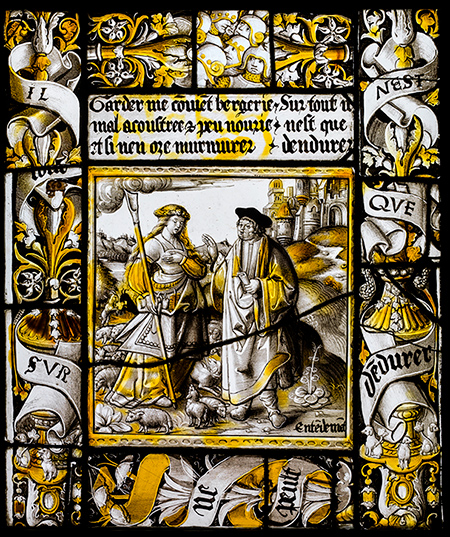

The arts became intertwined in Renaissance Europe. Paintings and sculptures were sources for prints, which in turn, were sources for art that adorned many objects, such as suits of armor, liturgical vestments, furniture, stained glass, and ceramics—including the examples selected from MAG’s Renaissance-era collections.

A 17th-century cabinet, for example, is adorned with 13 painted panels depicting scenes from Metamorphoses, by the Roman poet Ovid. The Flemish artist’s sources included an engraving that was, in turn, inspired by Titian’s painting The Education of Cupid.

A set of stained-glass panels, roundels, and windows from the 16th century “are particularly instructive,” Norwood says. She’s been developing a collection of glass over the last several years, and these selections, recent gifts, are being shown for the first time. They show scenes derived from woodcuts and engravings by the German Albrecht Durer, engravings by the Flemish Maarten van Heemskerck, and etchings by the Italian Marcantonio Raimondi.

She lists, one by one, the elements that went into the creation of the works. A Dutch painter working on Dutch glass, with a German engraving, derived from an Italian painting, as his source. A French artist working on French glass, including source images from a German engraving and an Italian etching.

As an exploration of the interconnections of commerce, travel, art, and imagery, Norwood says, “it just really sums it all up.”

Renaissance Impressions: Sixteenth-Century Master Prints from the Kirk Edward Long Collection, is on display at the University of Rochester’s Memorial Art Gallery through February 6, 2022.

Read more

A ‘different kind of wonder’

A ‘different kind of wonder’Associate professor of art history Christopher Heuer explores the European Renaissance’s engagement with the Arctic—a little-known chapter of history but a relevant one today, when the region once again has become a site of anxious attention.

In remote regions of the South Pacific, cell phones have transformed daily life

In remote regions of the South Pacific, cell phones have transformed daily life“There was a moment when they were nowhere, then a moment when they were everywhere,” says professor of anthropology Robert Foster about the cell phone in Papua New Guinea. Foster looks at how cell phones transformed a society overnight.

New book previews Memorial Art Gallery’s 2022 AIDS posters exhibition

New book previews Memorial Art Gallery’s 2022 AIDS posters exhibitionUp Against the Wall: Art, Activism, and the AIDS Poster explores the world’s largest collection of HIV/AIDS education posters and visual resources—a collection owned by River Campus Libraries and the basis for a major exhibition at the Memorial Art Gallery opening in March 2022.