The scholar made the British poet and “multimedia artist” accessible to a wide audience.

Morris Eaves, an English professor whose ceaseless and groundbreaking effort to digitize the illustrated poems of William Blake enabled widespread scholarship of the British poet’s work, died February 25 at the age of 79.

Family and friends describe his death as sudden and say a cause was not immediately known.

Eaves, who held one of the University’s Richard L. Turner Professorships of Humanities from 2010 to 2018, had been teaching two classes during the spring 2024 semester—Romantic Literature: Gothic Spirit, which explores the nexus of fantastical and terrifying works of British romanticism, and Media ABC, a historical introduction to media in a variety of forms.

He had been with the University of Rochester since 1986 and was known within the University community as much for his institutional knowledge as his devotion to the institution.

But Eaves was perhaps best known in academia for his scholarship on Blake and his pioneering preservation of Blake’s body of work in the internet age. His work on The William Blake Archive—an online initiative he pursued with two colleagues at other universities—has been the subject of scores of books, essays, and news articles.

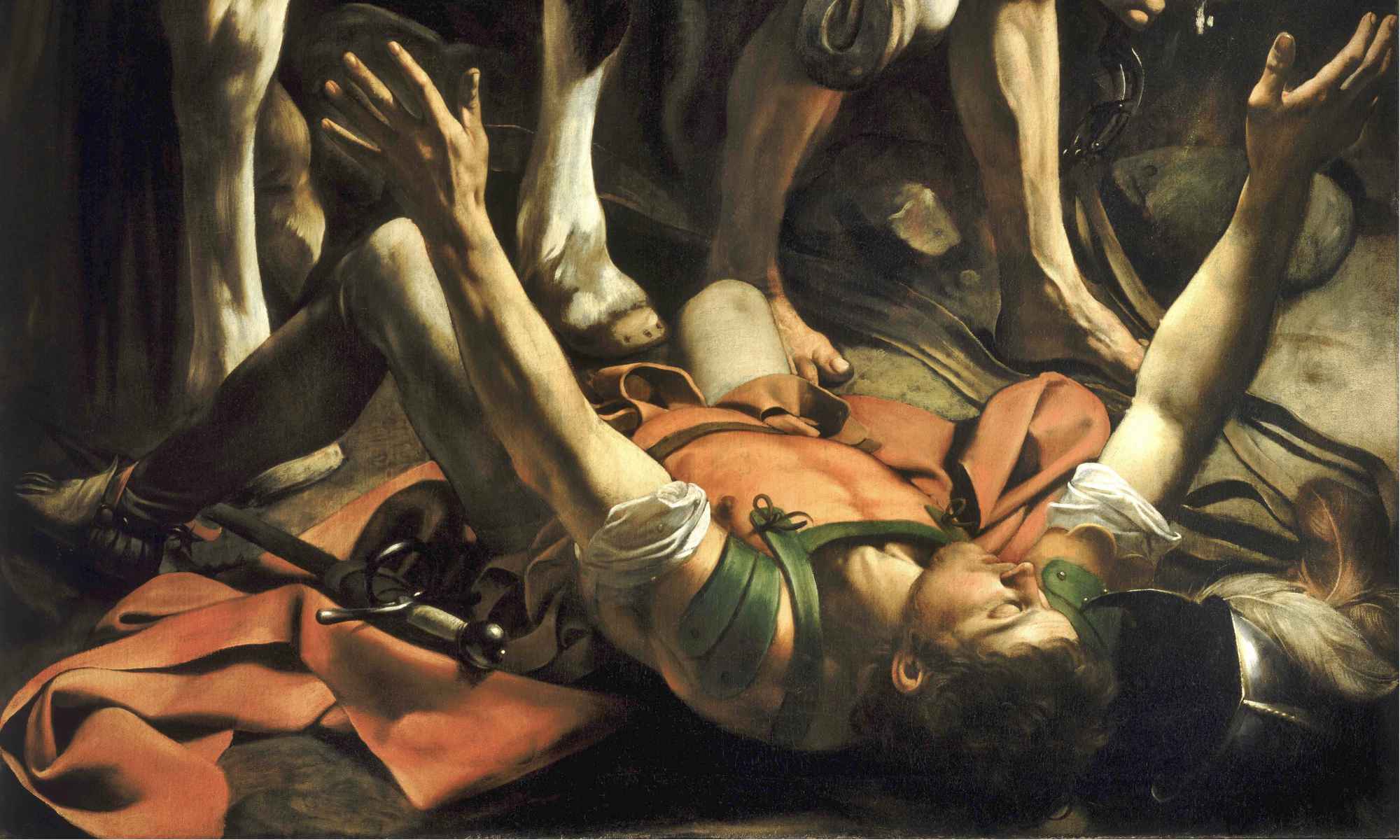

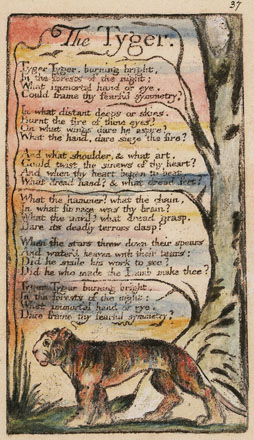

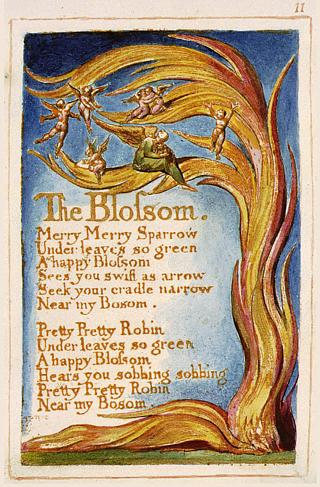

Blake is most often remembered as a poet. But he was also a painter, engraver, and printmaker who has been called the first multimedia artist for his hand-produced books of elaborately illustrated poems.

The breadth of his work, however, posed a major challenge for students of Blake for nearly two centuries after his death in 1827. Students were seldom able to fully experience Blake because his artworks were scattered amongst collections around the world and his poems were typically reproduced without their illustrations.

Eaves and two other top Blake scholars—Robert Essick of the University of California and Joseph Viscomi of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—sought to change that in the early 1990s when they began exploring the then nascent territory of digital humanities.

“I don’t remember when we first heard about the internet,” Eaves told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle of the pursuit in 2004. “Someone suggested it might be a way for us to go. . . . We got into it not knowing what the hell we were doing.”

They figured it out, though, and then some.

With a $250,000 grant from the Getty Grant Program, they began securing access to thousands of pages of fragile and expensive Blake materials and mapping out the infrastructure for how to digitize them.

Their creation, The William Blake Archive, was conceived in 1993 and began publishing its first digital editions in 1995. The online archive enabled researchers for the first time to easily compare versions of Blake’s poems, paintings, and prints, something that previously would have required costly travel. The project later received support from major corporations and would become a model for digital humanities projects involving historical texts and images the world over.

In the ensuing years, Eaves further enhanced the archive by overseeing the digitization of every edition of Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, a peer-reviewed journal devoted to Blake research that Eaves had coedited since 1970.

“We were really pioneers in creating this project,” says Viscomi, who recalls Eaves as a “first-rate Blake scholar” who was “crucial and central” to the initiative. “If you’re teaching Blake or studying Blake, you come to The William Blake Archive.”

Eaves grew up in West Monroe, Louisiana, and married his high school sweetheart, Georgia, in 1964 while he was a student at Long Island University.

When he earned his doctorate from Tulane University in 1972, it made news in his hometown. Under the headline “Local man to receive doctorate,” The Ouachita Citizen reported that Eaves had successfully defended his dissertation on “Blake’s Artistic Strategy.”

Decades later, Eaves described in the journal he edited how a rebellious spirit drew him to Blake as a graduate student. He wrote that giving up studying the likes of William Faulkner for Blake was a “self-shocking move,” but explained that he was “young, reckless, and fascinated by pictures as well as texts and by processes as well as products.”

“This was the ’60s after all,” he wrote, “when people got up to things they might have suppressed in more sensible times.”

Eaves taught for 16 years at the University of New Mexico before joining the Rochester faculty, where he would establish himself as something of an elder statesman of the English department.

During his tenure at Rochester, Eaves served as chair of the department for eight years and sat on dozens of committees on a medley of issues, from those that advised on the use of technology in the classroom to theater study and university apparel.

“He had been on so many committees for so many years that his loss is a major loss for the department,” says Nigel Maister, the Russell and Ruth Peck Artistic Director of the International Theatre Program, who calls Eaves a mentor and father figure. “He had significantly built the department over decades.”

Colleagues and friends use words like “brilliant,” “irreverent,” “unpretentious,” and “cheerful” to describe Eaves.

“He once said to me, and this was the best thing he ever said to me, ‘We take the work seriously, but we don’t take ourselves too seriously,’” says Sarah Jones, the managing editor of Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, who worked closely with Eaves.

Those who knew Eaves and his wife refer to them as an “inseparable” couple with discerning tastes in travel and food. It was understood, they say, that anyone dining out with the pair left the dinner reservations to them. That could mean sitting down at a Michelin-rated restaurant or a hole-in-the-wall crab shack to write home about.

Eaves is survived by his wife; their two sons, Obadiah and Dashiell; and three grandchildren, Emmeline, Ezra, and August. Ezra is a first-year student at Rochester.