We dug into our special collections to highlight a sampling of hand lettering, from ancient hieroglyphs to modern conscripts.

January 23 is National Handwriting Day, an annual celebration of penmanship, longhand, cursive, calligraphy, and other hand-written representations of language. Created in 1977 by the Writing Instrument Manufacturers Association, National Handwriting Day coincides with the birthday of John Hancock, who is known in part for his prominent signature on the Declaration of Independence.

In the midst of the digital age, the teaching of formal cursive handwriting has declined (most states, for example, no longer require public schools to teach cursive proficiency). However, the practice of handwriting remains useful for helping people develop fine motor skills, read primary historical documents, and send thank-you notes with a personal touch, among other benefits.

To show our appreciation for scribes and their tools of the trade, we dug into our special collections and news archives to bring you a sampling of hand lettering, from ancient hieroglyphs to modern scripts.

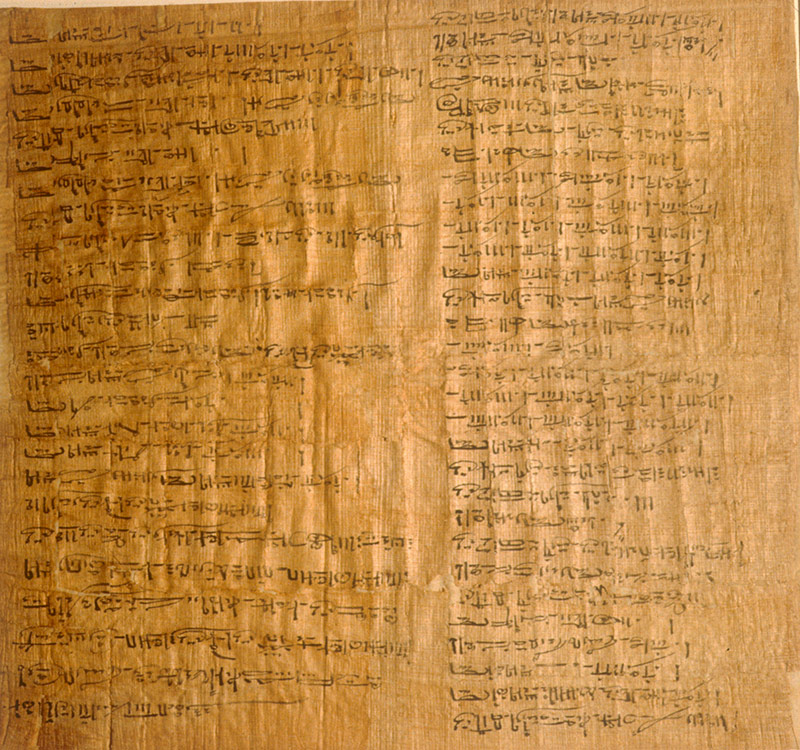

Write like an Egyptian

Part of the University of Rochester Memorial Art Gallery’s encyclopedic collection, this ink-and-papyrus manuscript dates to 2049 BCE. The sheet features hieratic writing, an abridged form of hieroglyphics used for record keeping because it could be written faster. The ancient Egyptians made sheets and scrolls from the stem of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus, from which we get the English word “paper.”

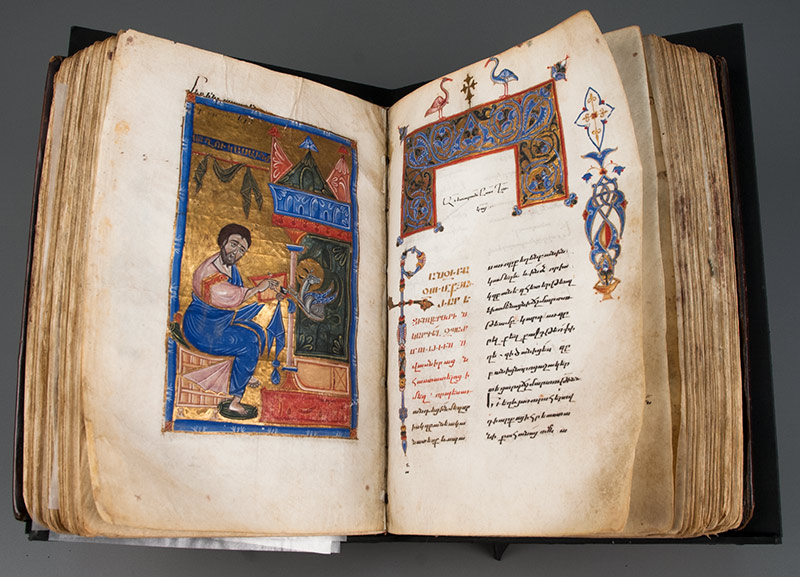

Medieval manuscripts on the move

This early 13th-century parchment manuscript was written by the scribe Grigor of Tarsos. The fragile manuscript traded hands during the Armenian Genocide in 1915, and came into the Memorial Art Gallery’s collections in 1950, where conservators have treated it in hopes of preserving it for generations to come. In a related effort to preserve cultural heritage objects, Rochester researchers are using multispectral imaging to digitally restore such ancient manuscripts.

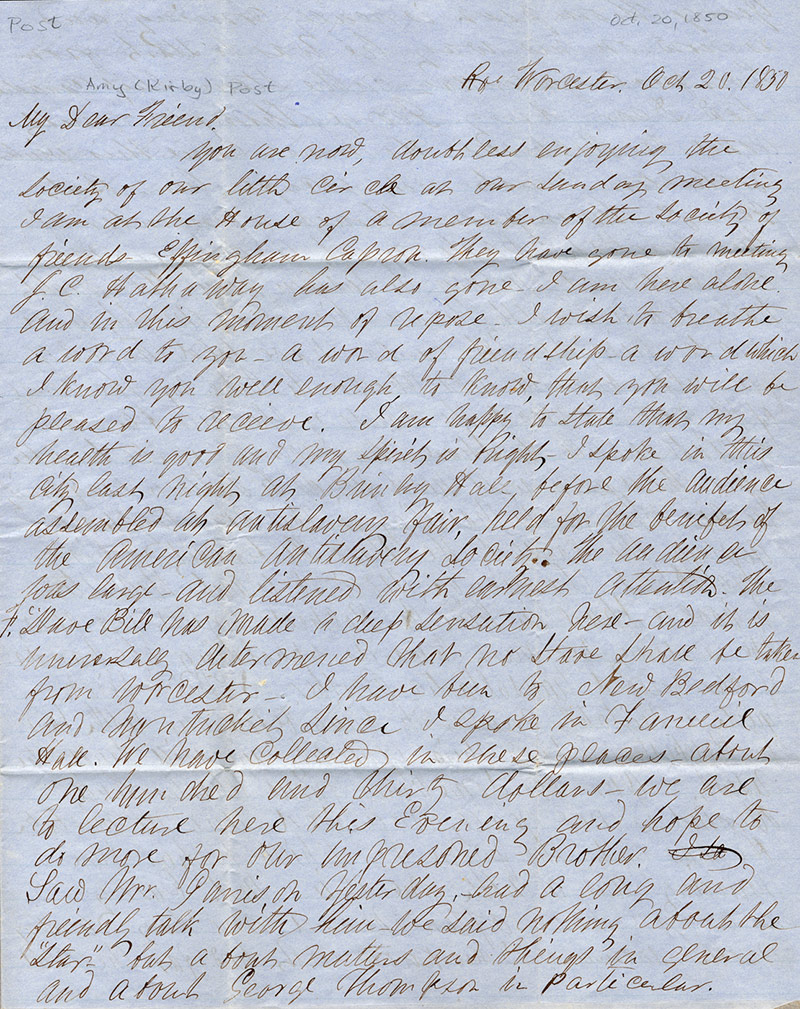

“My Dear Friend”

Former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass was a gifted orator (his 1852 speech delivered in Rochester is considered one of the “best Fourth of July speech(es) in American history”). He was also a skilled and prolific writer who published The North Star, an anti-slavery newspaper.

In this personal letter written in 1850 to fellow activist Amy Post, Douglass writes about his recent anti-slavery lectures: “I am happy to state that my health is good and my spirit is Right– I spoke in this city last night at Brinley Hall before the audience assembled at antislavery fair, held for the benefit of the American Antislavery Society. The audience was large–and listened with earnest attention.”

The letter in full reads:

My Dear Friend,

you are now, doubtless enjoying the

society of our little circle at our Sunday meeting

I am at the House of a member of the society of

Friends– Effingham Capron. They have gone to meeting

J.C. Hathaway has also gone– I am here alone

and in this moment of repose- I wish to breathe

a word to you– a word of friendship– a word which

I know you well enough to know, that you will be

pleased to receive. I am happy to state that my

health is good and my spirit is Right– I spoke in this

city last night at Brinley Hall before the audience

assembled at antislavery fair, held for the benefit of

the American Antislavery Society.. The audience

was large– and listened with earnest attention. The

F. Slave Bill has made a deep sensation here– and it is

universally determined that no slave shall be taken

from Worcester–. I have been to New Bedford

and Nantucket since I spoke in Faneuil

Hall. We have collected in these places– about

one hundred and thirty dollars– we are

to lecture here this Evening and hope to

do more for our imprisoned Brother. I sa

Saw Mr. Garrison yesterday, – had a long and

friendly talk with him–we said nothing about the

“Star-” but about matters and things in general

and about George Thompson in particular.

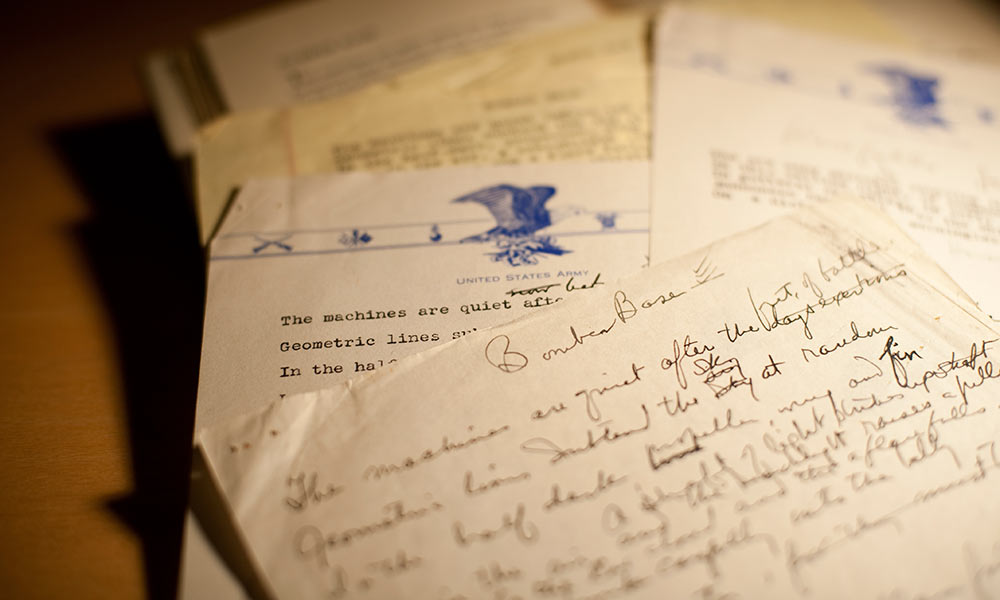

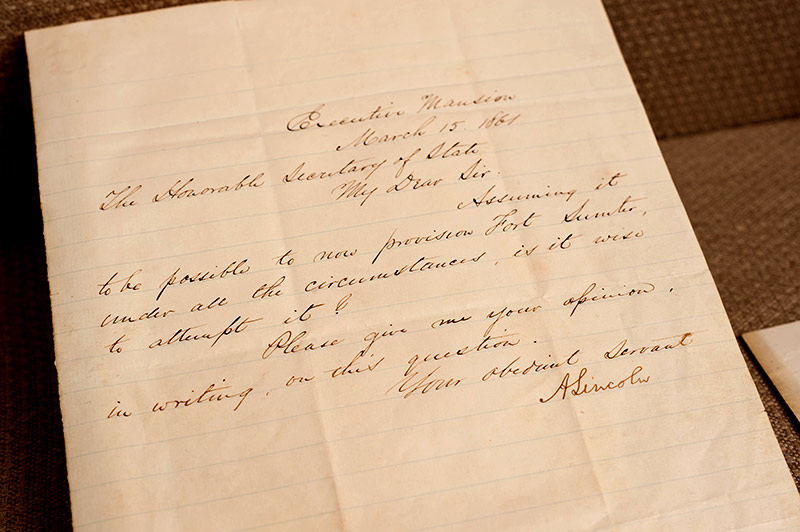

“Your Obedient Servant, A. Lincoln”

The William Henry Seward Papers is one of the most extensive collections of 19th-century American family letters known to exist. It includes 230 linear feet of materials, 150,000 items, and 375,000 pages, many of which are available digitally thanks to an intergenerational team of “citizen archivists” working together to decipher and transcribe the handwriting.

President Abraham Lincoln appointed Seward as his secretary of state in 1861. In a correspondence from that same year, Lincoln seeks Seward’s advice about sending aid to the Federal garrison in Fort Sumter in the Confederate-held Charleston Harbor.

The full transcript of the letter reads:

Executive Mansion

March 15, 1861

The Honorable Secretary of State

My dear sir,

Assuming it to be possible to now provision Fort Sumter, under all the circumstances, is it wise to attempt it?

Please give me your opinion in writing on this question

Your obedient servant

A. Lincoln

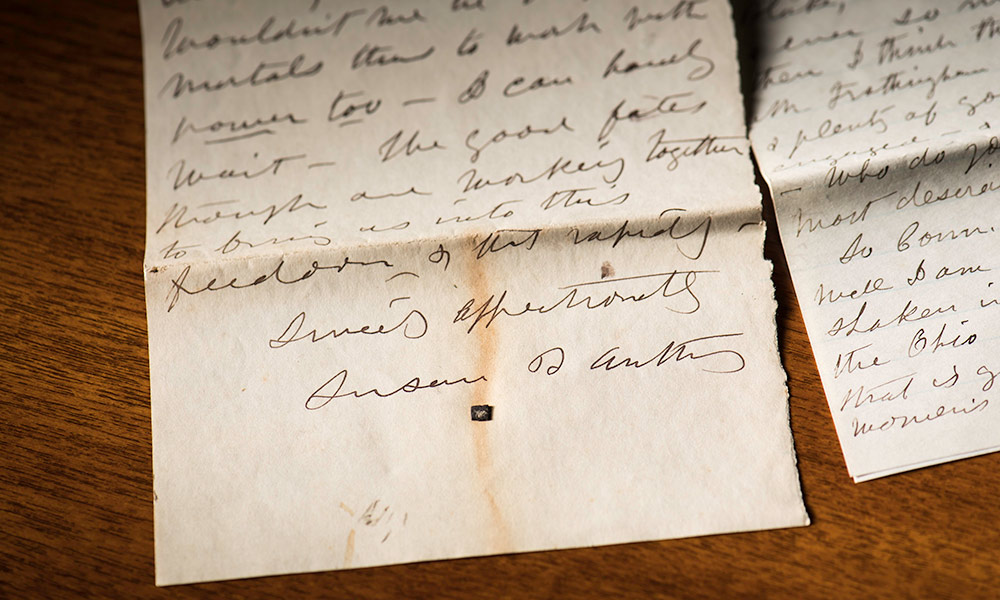

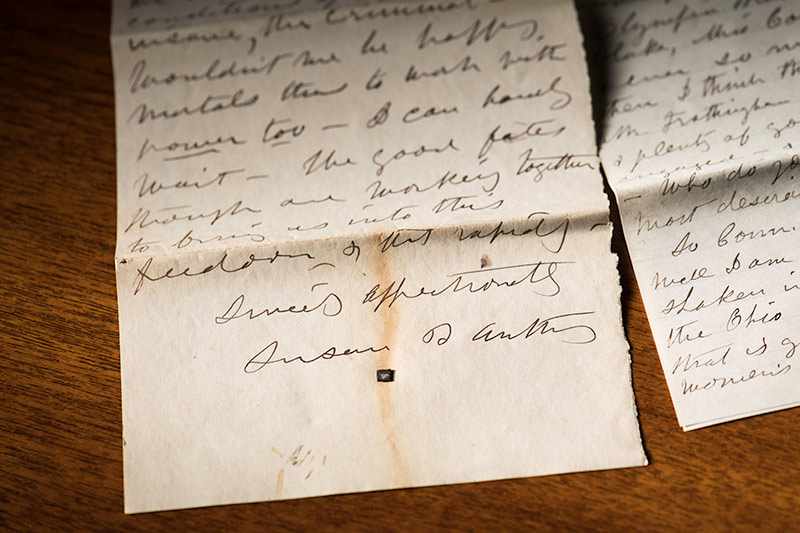

Suffragists show their work

This letter from Susan B. Anthony to fellow suffragist Isabella Beecher Hooker is one of a trove of documents discovered last year that also includes missives written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Unlike other Anthony letters already in the University’s holdings, this collection is thoroughly political—rarely personal—as it showcases the methods and machinations of those leading the early women’s rights movement.

Anthony concludes this 1874 communiqué by reflecting about the work that women could do on behalf of the poor, criminal, and insane if they had the power to vote. She writes: “now wouldn’t it be splendid for us to be free & equal citizens—with the power of the ballot to back our hearts, heads & hands.”

The handwriting reads:

Wouldn’t we be happy

mortals thus to work with

power too — I can hardly

wait — The good fates

though are working together

to bring us into this

freedom and that rapidly.

[Sincere?] affectionately

Susan B. Anthony

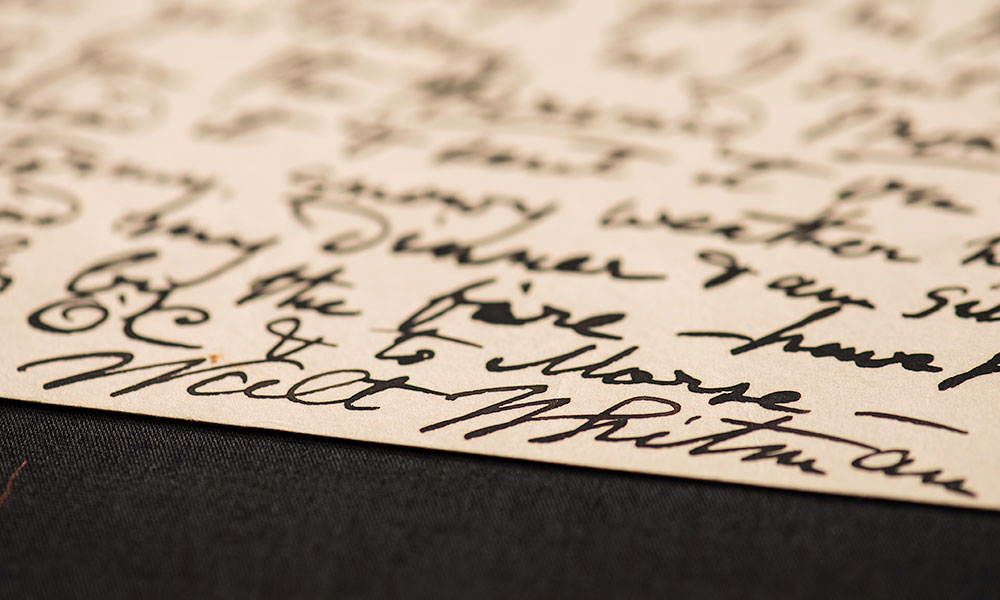

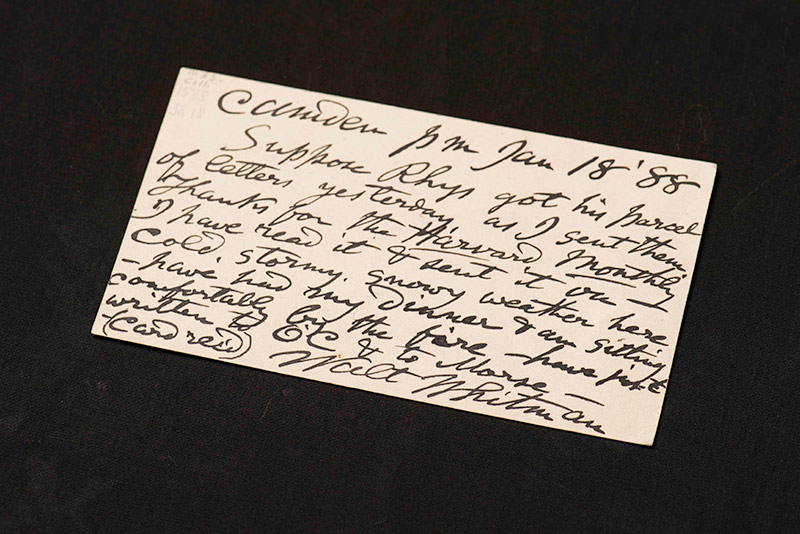

A poet and his pen

Walt Whitman is one of the most influential voices in American literature. The “Song of Myself” poet wrote this postcard to William Sloane Kennedy, one of his avid supporters, in January 1888.

“It’s enlightening for students and researchers to see and experience these hand-written documents, connecting with their authors through these intimate exchanges, decades or sometimes centuries after they were written,” says Jessica Lacher-Feldman, assistant dean and the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, which now houses the postcard.

The full handwritten text is as follows:

Camden PM [?] Jan 18 ‘88

Suppose Rhys got his parcel

of letters yesterday, as I sent them.

Thanks for the Harvard Monthly

I have read it and sent it on—

Cold, stormy, snowy weather here

—have had my dinner & am sitting

comfortably by the fire —have just

written to OC [?] & to Morse—

–(card rec’d) Walt Whitman

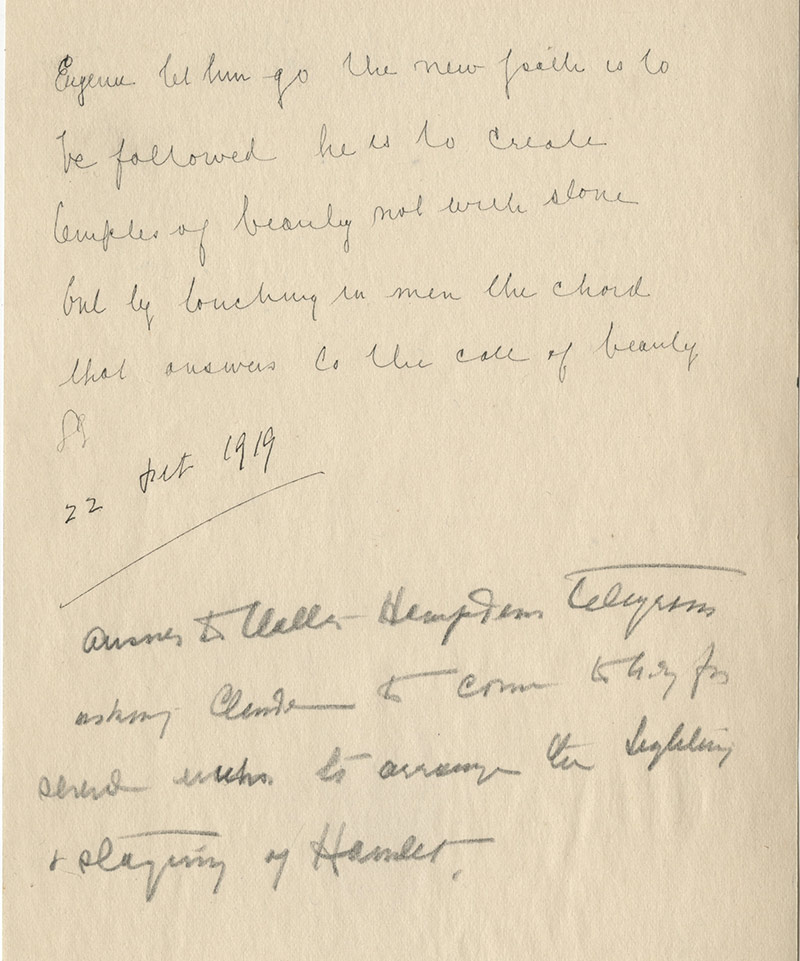

Ghostwriter

Claude Fayette Bragdon was a Rochester-area architect, author, and theater designer whose second wife, Eugenie, engaged in automatic writing: she would go into a trance or altered state, then write in handwriting that was not her own. All of Eugenie’s automatic writing began with “Eugenie” and ended with the “squiggles” that resemble SSSS or loose ampersands. She would then add her “conscious” caption below the message.

In 1921, Claude published the psychic communications Eugenie received from an “Oracle.” Today, the River Campus Libraries house the Bragdon Family Papers.

The entirety of this particular letter reads as follows:

Eugenie let him go the new path is to

be followed he is to create

temples of beauty not with stone

but by touching in men the chord

that answers to the call of beauty

[SSSS]22 Feb 1919

answer to Walter Hampden telegram

asking Claude to come to N.Y. for

several weeks to arrange the Lighting

& staging of Hamlet.

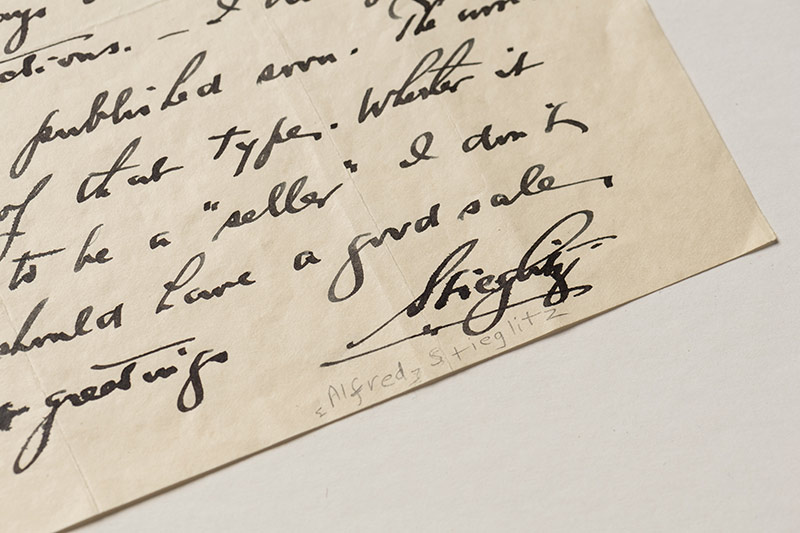

Pen pals

Reading personal letters and diaries can “breathe new life into some of history’s most interesting personalities,” writes Lacher-Feldman. Case in point: Alfred Steiglitz, the photographer, art promoter, and husband of artist Georgia O’Keeffe. Steiglitz corresponded regularly with Claude Bragdon, whose personal papers are housed in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation.

In this 1937 letter, Stieglitz writes to Bragdon, “It is 22 days since your letter came” and begs the latter to “forgive my procrastination.” Stieglitz also mentions that O’Keeffe recently visited Frieda Kahlo, and that he has been spending time with Swami Vivekenanda.

The letter from Stieglitz conveys the following:

I do hope the

book will be published soon. The world

needs books of that type. Whether it

will prove to be a “seller” I don’t

know. It should have a good sale.

My kindest [?] greetings

Stieglitz

Conlang creations and Rochester research

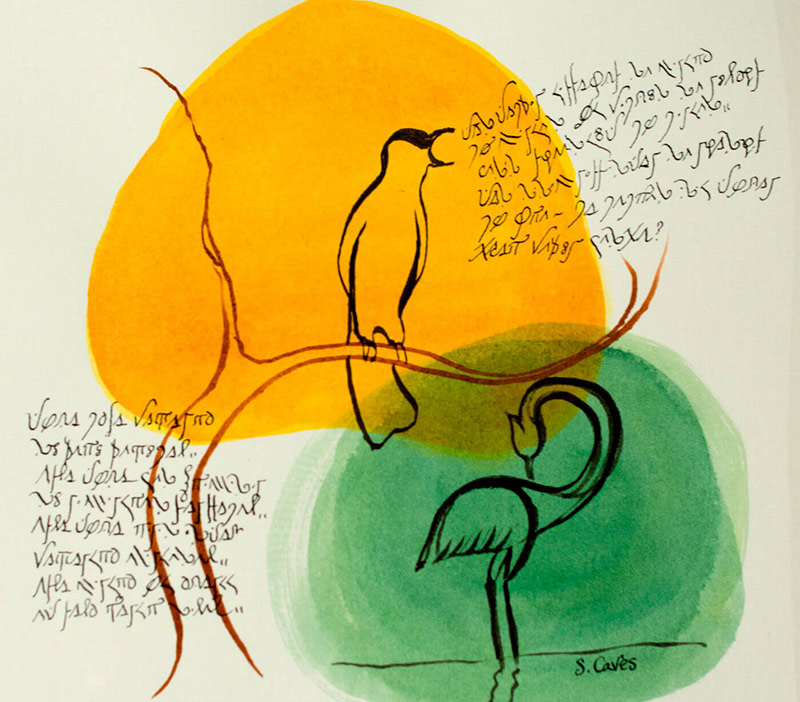

Professor of English Sarah Higley has long been fascinated by languages, both real and invented. As a child she created her own constructed language, or “conlang,” called Teonaht. Under the sobriquet Sally Caves, Higley continues to refine Teonaht and has gone so far as to devise a new writing system to accompany it. In this image, you can see a sample of a handwritten song in Teonaht embellished with Higley’s own artwork.

As part of her academic research, Higley wrote a book exploring and contextualizing the invented vocabulary of Hildegard of Bingen, the 12th-century German nun who created the first entirely artificial language on record, complete with a related alphabet: the literrae ignotae. Learn more about the study and creation of conlangs at Rochester.

Here is the translation of Higley’s creations:

The Teonaht script in Roman characters:

Vul vampin dittahuot

le htindro ‘mai htindel.

Aid fimuõl le nõsoyt

celil tyeeldõv ‘mai mindel.

Vul liliht nittilvan

le nyalyt ‘mai hre;

Ma nemral ilid vaiuan

kwa’r fepõn celkke?The literal translation:

Of heroic deeds does

the starling’s song sing.

The heron its clothes

in the morning rain washes.

By night the stars

does the lark worship;

But the true heart of birds,

who observes it?