Ask any contract attorney: the slightest of typographical changes can have profound ramifications.

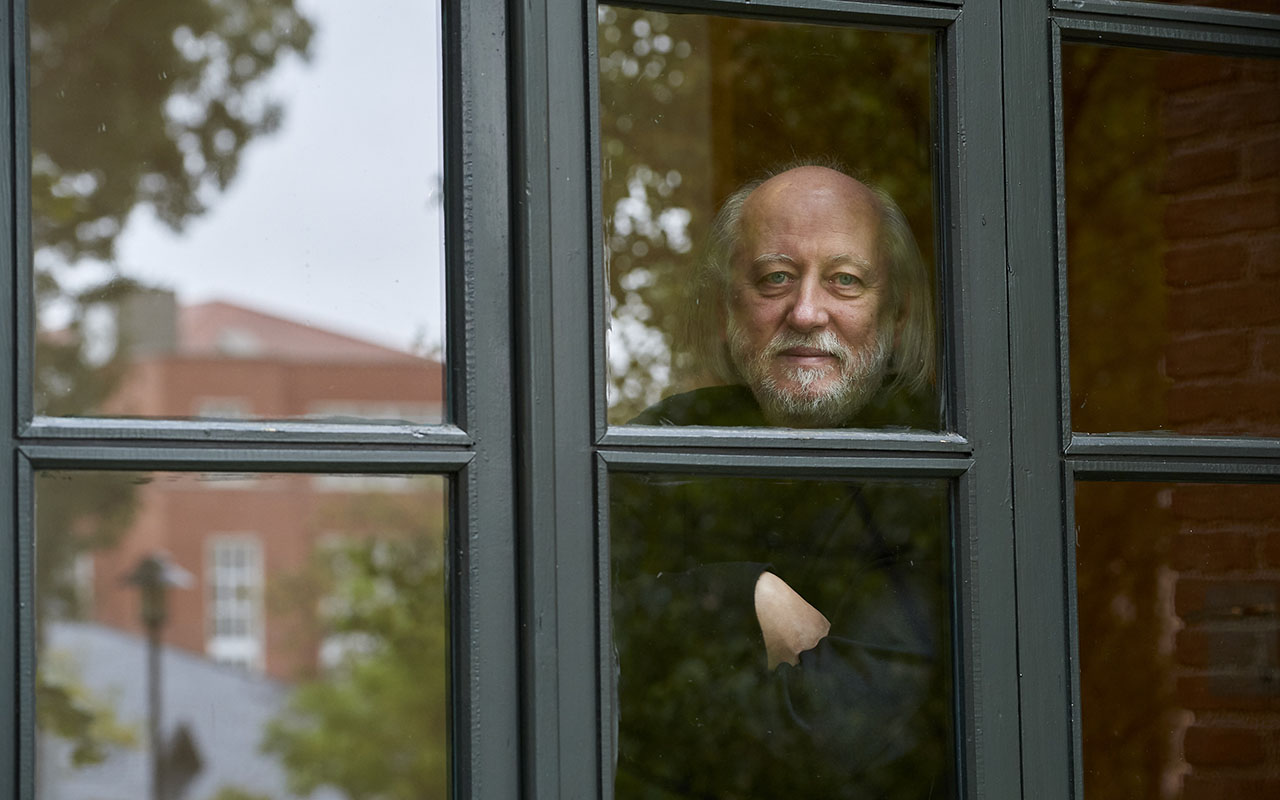

Susan Gustafson, the Karl F. and Bertha A. Fuchs Professor of German Studies, agrees. As evidence, she points to the difference between “You love me!” and “You love me?” The substitution of a question mark for an exclamation point “changes the meaning completely,” she says.

That particular edit is just one of 100 changes Johann Wolfgang von Goethe made to his 1776 play, Stella: A Play for Lovers, when he rewrote it 30 years later. He withdrew the original production from theaters after just 10 performances—audiences rejected the play because of the polygamous relationship established in its closing scene.

In 1806, he brought it back to the stage with a revised script. Now titled Stella: A Tragedy, the new play ended with the suicides of two of the three main characters.

“That’s what made the play acceptable in its time, I guess,” says Gustafson.

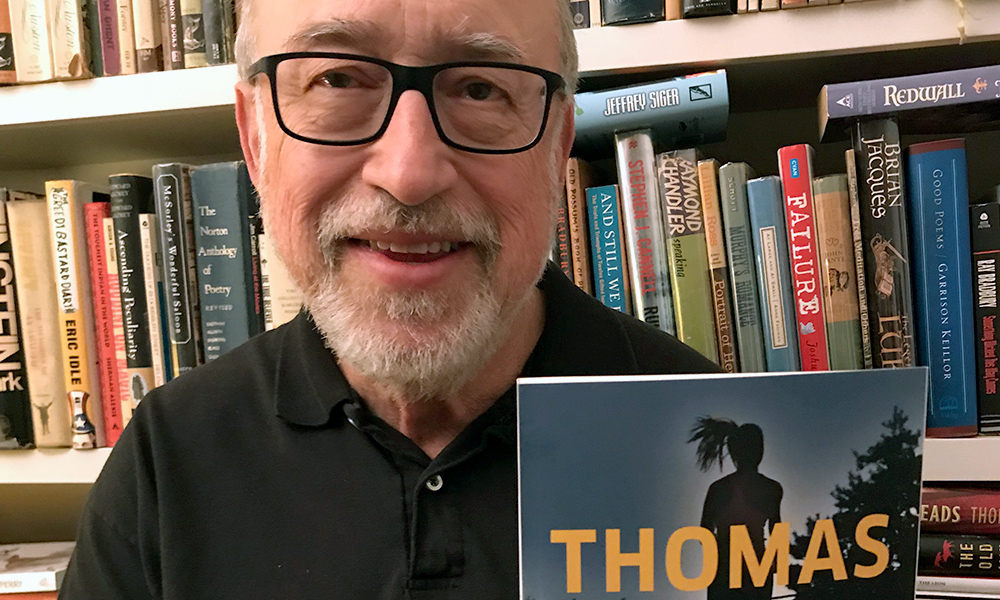

With Kristina Becker Malett, an assistant professor of instruction in German, Gustafson has just published an English translation: Stella: A Play for Lovers (1776) (Peter Lang, 2018). It’s the first time the original script has been rendered in its entirety in English, and the edition includes an appendix documenting all of the differences between the 1776 and 1806 texts.

Stella is one of the famed German writer’s lesser-known works. It tells the story of the rakish Fernando and two of the women he has romanced and abandoned: Cecilia and Stella. Scholars—working in both the original German and in English—long assumed that the only notable difference between the versions is the play’s ending. In fact, a 1993 English translation by two German scholars that purported to be the original text offered exactly that, reproducing what was otherwise the 1806 text with the 1776 conclusion restored.

But Gustafson and Malett’s scrupulous, side-by-side examination of the two plays revealed something different. “Some of the changes are just punctuation. In other cases, whole passages were left out,” Gustafson says. The changes affect the play from start to finish, and while Goethe removed and downplayed elements that led to the play’s retraction, he retained the women’s relationship in the 1806 version, and even strengthened it.

Gustafson argues that polygamy, in the 1776 text, is a means for the women to secure their own connection in a culture that wouldn’t accept intimate, romantic relationships between women. While many scholars have read the women’s affiliation as a sisterly or companionate one, she suggests that it’s a fully realized alternative to their partnerships with Fernando. Their “feelings for one another are the strongest in the play…and not simply a lesser compensation for the loss of Fernando,” she writes in her book Goethe’s Families of the Heart (Bloomsbury Academic, 2016).

Gustafson and Becker Malett created their edition to provide a text not just for scholars but also for students of German and comparative literature, general readers, and community theater groups.

The play tackles issues of enduring interest: the ways in which women and men understand each other, the expectations they bring to marriage, and the complexities of attraction, friendship, love, desire, and exclusivity. Stella’s concerns “resonate with contemporary ideas about love relationships,” says Gustafson, “and, in several different ways, raise the question, what is love?”

Throughout his many works, Goethe stresses love as the foundation of relationships, she says. And he did so living in a culture where marriage matches were typically determined by economic factors. It was a radical position to take.

“Goethe was really an outlier in stressing that love was more important.”