Women of Invention is a Newscenter series of profiles of women at the University who hold international patents. More than half of the University’s patent applications from 2011 to 2015 include women.

As she was being recruited by the University of Rochester, Danielle Benoit had an opportunity to meet with Edward Puzas, the Donald and Mary Clark Professor in Orthopaedics and an expert in bone remodeling.

“Just to talk about what he was doing, what I was doing, and what we might do together,” recalls Benoit, an associate professor of biomedical engineering.

Puzas told her about his research into the “crosstalk” that occurs between the cells that continually remodel our bones. He had discovered that the osteoclasts in charge of breaking down depleted bone tissue leave behind “molecular signatures”—so the osteoblasts charged with rebuilding the bone will recognize where they are needed.

“Is that at all interesting?” Puzas asked her. “Could that be useful for something?”

“Yes—and yes,” was Benoit’s reply. That conversation was one of the reasons why Benoit ended up accepting a faculty position in the University’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

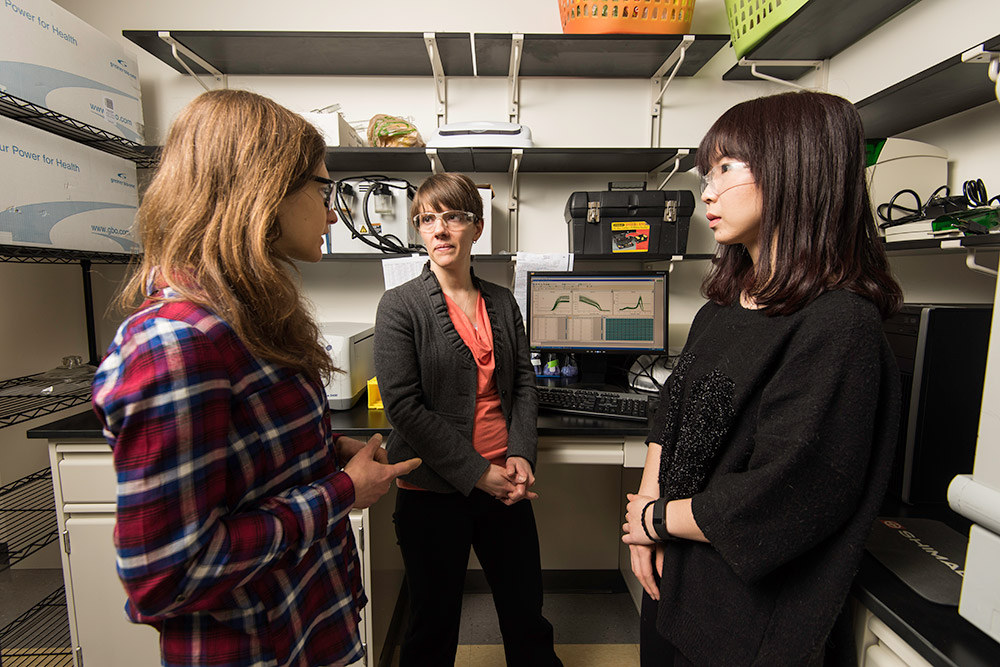

The number of women among the department’s faculty members was another.

“It wasn’t just women who were junior faculty members, but women who were senior and very well established, and who had thriving research programs,” Benoit says. “To me, that suggested that Rochester was going to support that kind of career development.”

The close proximity of the department to the University’s medical center, just across Elmwood Avenue, was also “critical,” she says. It offered Benoit easier access to basic science researchers like Puzas who could help her advance her work in tissue regeneration, and also the targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs, which she began as a postdoc.

For example, the fact that osteoclasts leave behind molecular signatures “is a fantastic way to target bone drug delivery to exactly where it’s needed,” Benoit says.

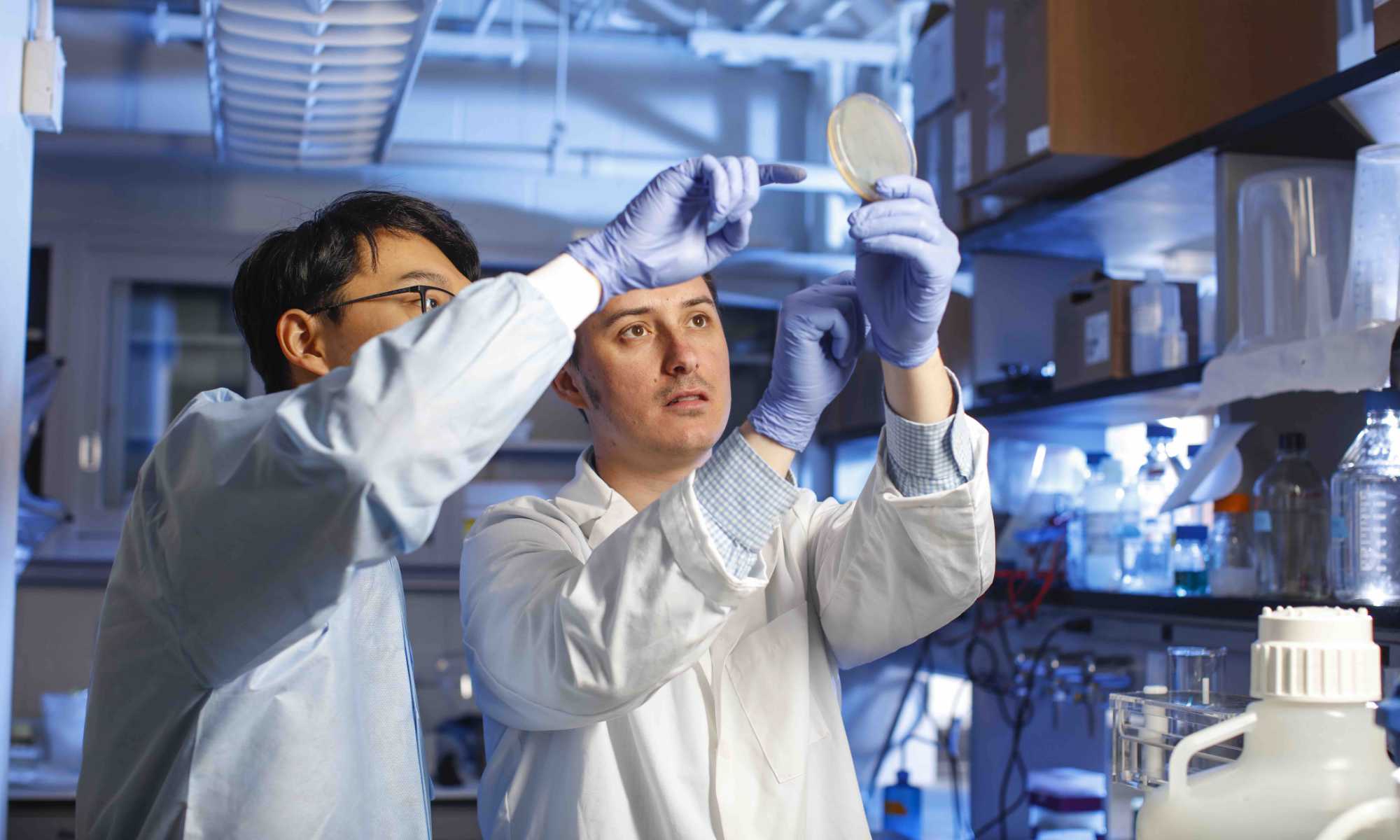

Here’s how: One of those molecular signatures is a protein called tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, or TRAP. Working with Puzas, Benoit’s lab began to design a nanoparticle-sized polymer drug-delivery device that includes a peptide that binds to TRAP. In theory, the package could be loaded with therapeutic drugs to enhance the bone rebuilding process—in the case of a fracture—or to boost the performance of deficient osteoblasts—in the case of osteoporosis, or chronic bone thinning. It might even be used to target leukemia stem cells deep in the marrow of bone.

“By getting those drugs directly to the osteoblasts, we would have greater impact,” Benoit says. “And because we’re delivering the drugs to just that particular cell type, we would reduce the possibility of ‘off-target’ side effects in other parts of the body.

“It took a number of years, but that’s what we’ve done.”

The result was US Patent #9,949,950: “Compositions and Methods for Controlled Localized Delivery of Bone Forming Therapeutic Agents,” one of nine approved or pending patents Benoit has co-authored.

Another of her patents, with Hyun Koo at the University of Pennsylvania, is for a nanoparticle carrier that binds to tooth enamel. It releases a therapeutic drug to reduce plaque and prevent tooth decay at exactly the right time, triggered by acidic levels that occur in the presence of glucose, starch, and other food products that cause tooth decay.

‘Always tinkering’ as a kid

Benoit, who grew up in Maine, says she was “always tinkering” as a kid, making race tracks for matchbox cars, for example. She remembers tagging along with her father at work for a couple of days. He was trained as a forester, but worked essentially as a civil engineer, designing remote logging roads for his company. “I remember all the survey equipment and other gadgets he had. I thought that was really cool,” Benoit says.

She would spend hours exploring the woods next to her home.

“I loved every science class that that I came across,” she adds. “Even in middle school, I remember going into earth science and thinking ‘this is so cool.’ ”

She was the first student to graduate in bioengineering from the University of Maine. She completed her PhD in chemical engineering at the University of Colorado in Boulder, then did her postdoctoral research at the University of Washington in Seattle. She developed a delivery system for nucleic acid drugs, “which are really challenging to deliver,” for cancer therapy.

She says she’s thankful that she was schooled in the importance of disclosing technologies developed in an academic lab, and in securing patents for them.

“That’s critical, if we want to see what we have developed become a product that’s going to help people, especially a drug delivery system or tissue engineering product. It’s going to take an investment in safety and efficacy studies, and clinical trials, and so much development that is beyond the scope of what we can do in our labs,” Benoit says. “A company is not going to be interested unless the technology is protected. It’s not going to be worth it to them if another company is going to do it, too.”

She delivers the message to the students in her lab, including more than 80 undergraduates she has mentored since joining the University in 2010.

“These students are challenged with true research projects, are provided excellent training in key skills, and are guided by a hierarchy of mentors and role models that includes graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, and Professor Benoit herself,” says Diane Dalecki, the Kevin J. Parker Distinguished Professor in Biomedical Engineering and department chair. “It is impressive how often undergraduate students are included as co-authors on papers from Professor Benoit’s laboratory.”

“Keep exploring, keep learning,” is Benoit’s advice for young would-be inventors and researchers.

That’s the path she followed, from the woods of Maine to cutting-edge research and inventions at the University of Rochester.