A Rochester undergraduate discovers that prospective voters perceive female politicians as more extreme than their male counterparts.

Morgan Gillespie ’23 had more than a hunch.

Combing through literature on gender bias among American voters, Gillespie, a political science major at the University of Rochester, found a curious gap. While many researchers agreed that a candidate’s gender influences prospective voters—the nagging question of how and in which ways had not been answered satisfactorily. Moreover, she found little scholarship that sought to measure voters’ perceptions of ideological differences between men and women seeking public office.

That’s why, with some help from her honors thesis advisor Scott Abramson, an associate professor in the Department of Political Science, she devised and conducted an experiment that examines the connection between a politician’s gender and voters’ perception of that politician’s policy preferences.

Gillespie’s findings are preliminary. This summer, she and Abramson will widen the study and prepare a paper that they hope to publish in a top peer-reviewed journal. The data from her experiment will serve as the foundation. As her advisor puts it, Gillespie has produced “a kick-ass honors thesis” that will serve as “a pilot for a more comprehensive experiment based on a nationally representative sample.”

What Gillespie has found so far is striking.

Her results show that voters (both male and female) use gender cues to form beliefs about which policies a politician supports. When voters are unaware of a politician’s party affiliation, women politicians are seen as more liberal than otherwise identical men. However, when party affiliations are known, female candidates are seen as more ideologically extreme than male candidates of the same party. Furthermore, what has widely been labeled “women’s issues,” or issues that women candidates are more likely to support—such as abortion, paid family leave, or the gender wage gap—are perceived as more ideologically liberal issues or extreme positions. Gillespie found very little difference between male and female respondents in her experiment.

If the findings bear out, Gillespie will have provided evidence against the conclusions of an often-cited meta-analysis from 2020, according to which voters appear to prefer women candidates for public office.

The studies on which the meta-analysis is based “are conflating a preference for women with beliefs about the candidate’s ideology or party affiliation,” Gillespie says. “The conclusions from these previous studies misinterpret the positive effect of gender.” She notes carefully that her and Abramson’s findings suggest an additional source of bias that these experiments “fail to uncover.”

Departmental program identifies promising undergraduate researchers

Gillespie, who came to Rochester from San Diego, California, is part of the highly selective political science honors program that enables senior undergraduates to conduct original social science research in a small, collaborative setting. Stellar students are invited into the program by the department faculty, generally in the spring of their junior year. As Abramson tells it, Gillespie was a shoo-in.

“She’s clearly one of the best undergraduates in our department,“ he says, pointing to her abilities as a researcher, coupled with her strong work ethic and insightful questions. “The progress she makes week to week is more than I expect from most graduate students.”

Gillespie has broad intellectual interests that made her pursue minors in international relations, legal studies, and art history. She’s also deeply involved in numerous campus activities, including the student government’s judicial council, mock trial, the pre-law society, the Gamma Phi Beta Sorority, and the women’s rugby team. As if this were not enough, she has been working at the New York State Office of the Attorney General where she works in mediation for the Consumer Frauds and Protection Bureau.

Measuring for gender bias

In order to quantify bias based on a candidate’s gender, Gillespie created six hypothetical candidate vignettes such as the one below, into which she randomly assigned pronouns (she or he) to provide gender cues.

Politician 1 was born in Dallas, Texas in 1983. He received his B.A. from Baylor University in 2005 and his J.D. from the University of California, Berkeley in 2014. He was worked as a professional athlete, a nonprofit executive, and a lawyer. He is married and has no kids. Assume Politician 1 was asked to vote “yea” or “nay” for each of the following bills. Please select the bills you believe he would vote “yea” for.

- This bill establishes a national health insurance program. The program will cover all US residents and provide for automatic enrollment of individuals upon birth or residency in the United States.

- This bill prohibits an abortion of an unborn human individual with a detectable heartbeat and creates a Joint Legislative Committee on Adoption Promotion and Support.

- This bill establishes measures to expand access to higher education by eliminating tuition and fees for eligible students and reauthorizing certain programs to assist students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

For a portion of these fictitious candidates, Gillespie randomly assigned a specific party affiliation—either Republican or Democrat—to measure the effect of partisanship. Then she asked a sample of 506 American respondents to predict the candidates’ vote choice—yay or nay—across a list of 18 electoral bills.

Gillespie asked the respondents where they thought the six candidates stood on a wide range of issues, such as climate change, police accountability, the safety of police officers, immigration, free school lunches, abortion, the health of incarcerated women, gun safety, minimum wage, national health insurance, support for the armed forces, national security, the gender wage gap, paid family leave, voting restrictions, and access to higher education.

With the help of her advisor, whose research aligns with her topic, Gillespie estimated parameters of a discrete choice model—similar to those models commonly used in the analysis of legislative roll-calls—which typically explain a choice between two or more distinct options that are mutually exclusive.

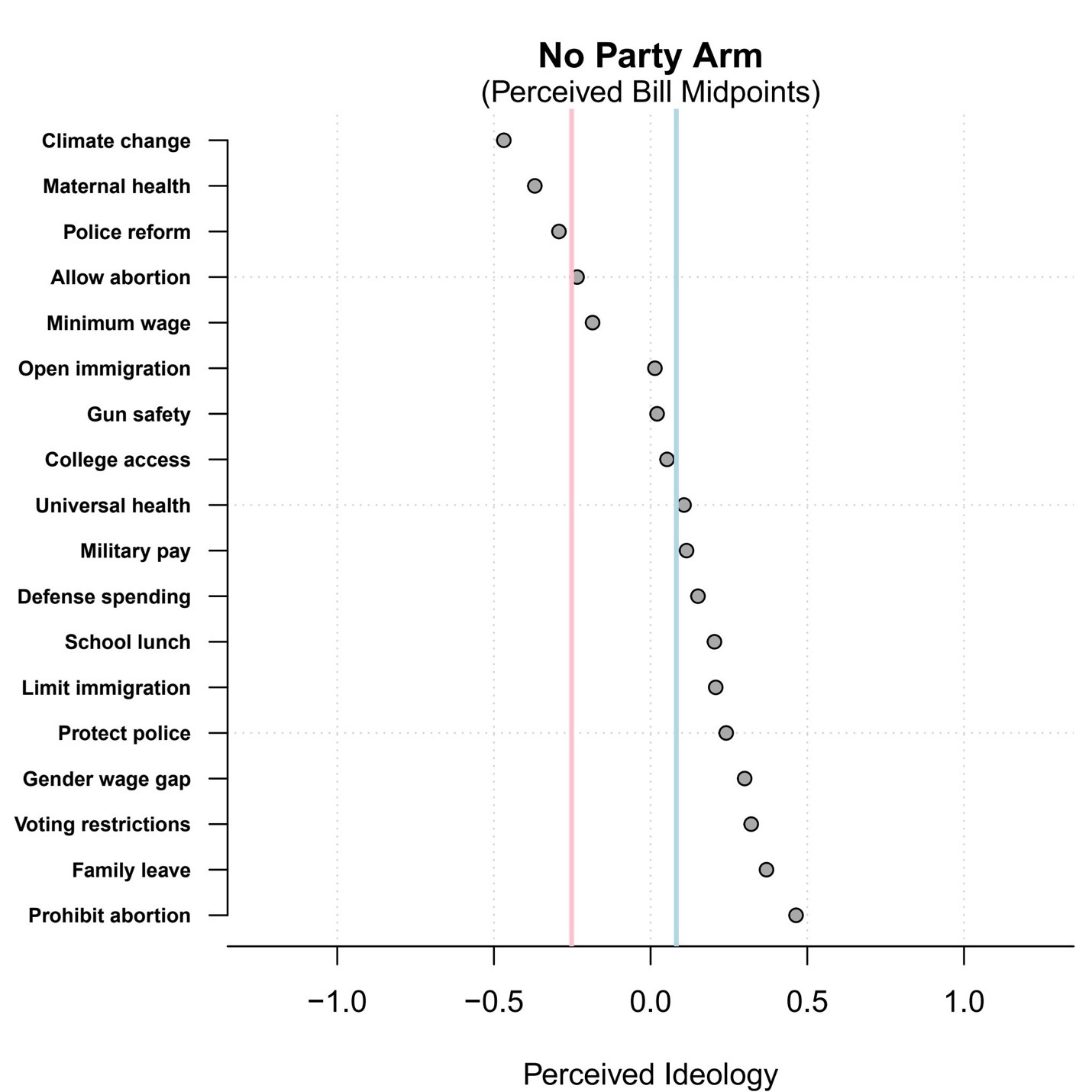

The graphic shows respondents’ estimates for candidate positions without having been provided a candidate’s party affiliation. Here the fictitious female candidates (pink line) score as “more liberal” (to the left of zero) than their fictitious male counterparts (blue line). (Source: Morgan Gillespie)

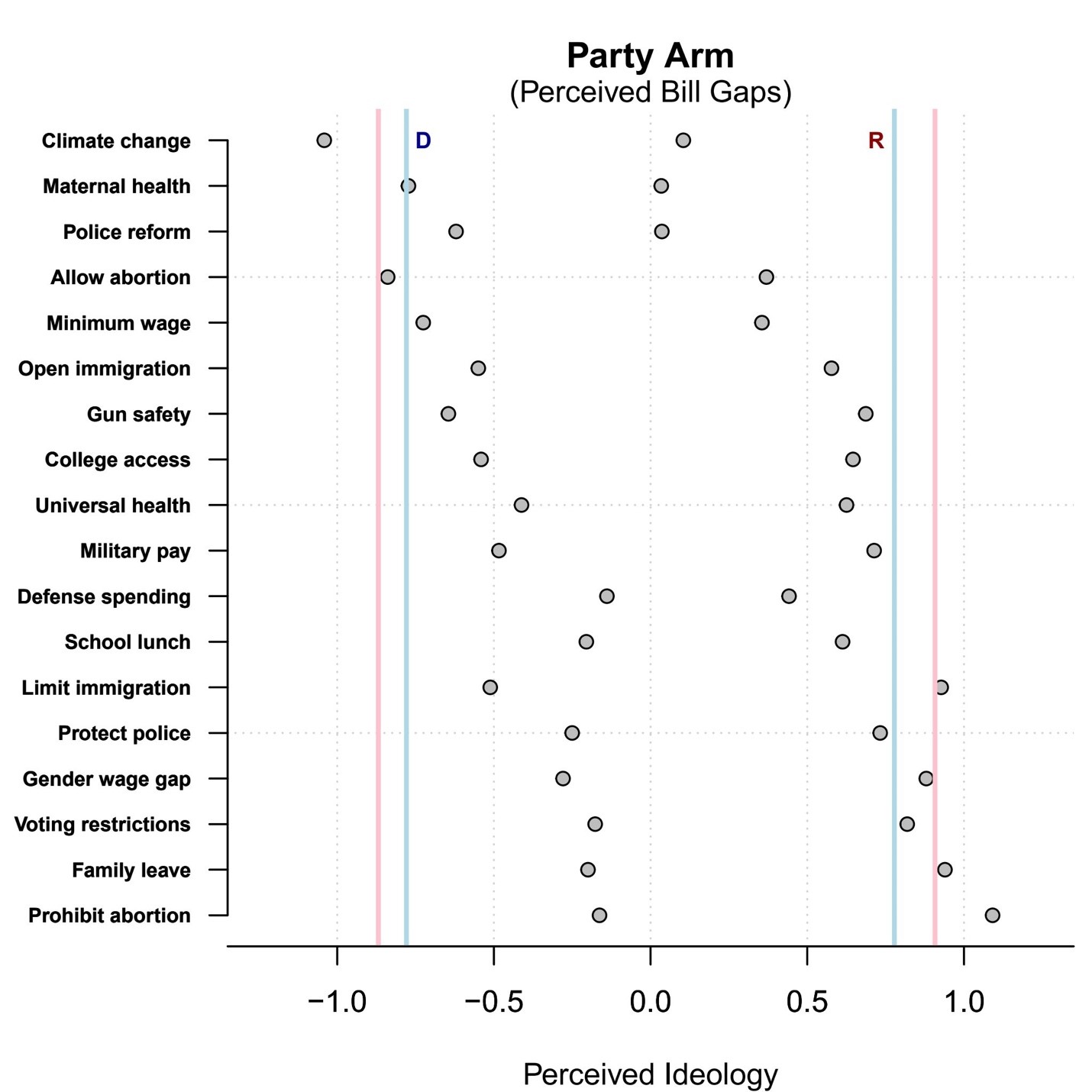

The graphic shows respondents’ estimates for candidate positions after having been provided with a candidate’s party affiliation. The gap between the perceived positions of fictitious female and male candidates now decreases, yet in both instances female candidates are seen as more extreme: Democratic women (pink line D) are located politically to the left of their Democratic male counterparts (blue line); while Republican women (pink line R) are located politically to the right of their male counterparts (blue line). (Source: Morgan Gillespie)

The results boil down to a double-whammy effect for women candidates at the ballot box, regardless of their party affiliation. First, in a political culture in which centrism is associated with greater electability, female politicians are seen as more extreme than their male counterparts. Second, the issues that women may support are also viewed as more ideologically liberal. Yet, female candidates may face strong pressure to campaign on issues that are more broadly supported by women, or that are categorized as “women’s issues.” Taken together, Gillespie says, these two biases can make female candidates appear more extreme and thus less electable than otherwise identical male candidates.

The road ahead

The project has proved potentially life-altering for Gillespie. Originally, she had planned on applying to law school after graduating from Rochester this May. But once she got started on the research for her honors thesis, things began to shift.

“I realized research was something that I had the skills for, something that I learned here at Rochester,” says the 21-year-old. That skill building didn’t happen in the classroom alone but also came with leadership roles across campus organizations and clubs, which built her confidence in “communicating my ideas and advocating for myself.”

Upon graduation Gillespie will head to the East Coast for a year as a political science research associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), with the ultimate goal of pursuing a PhD in political science.

“I realized that if I applied and pushed myself, I would be able to investigate issues that I always had questions about but that I didn’t think I’d be able to find the answers for,” says Gillespie, summing up her experience with her honors thesis research. With that came the realization that “people will stand behind me and support my ideas.”

Read more

English major from The Gambia helps preserve ancient African fables

English major from The Gambia helps preserve ancient African fables

Fatoumatta Jobe is transcribing in Wolof—and then translating into English—centuries-old stories passed down orally.

Lab experience your first year in college? Yes.

Lab experience your first year in college? Yes.

With faculty and graduate student mentorship, undergraduate researchers thrive in the Rochester Human-Computer Interaction lab.

Julia Granato crisscrossed Europe to study human bone collection and display sites. Now she’s pondering what it means to display and visit human remains.

The ethics of dark tourism

The ethics of dark tourism