Bestselling author Cheryl Mendelson ’73 (PhD) discusses marital vows, including their history and role, and why ditching the classic ones may be a bad idea.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cheryl Mendelson holds a PhD in philosophy from Rochester and a JD from Harvard Law School. She has practiced law in New York City and taught philosophy at Barnard College, Columbia University, and Purdue University. She is also the author of the bestselling Home Comforts: The Art and Science of Keeping House, a trilogy of novels about Morningside Heights, and The Good Life: The Moral Individual in an Antimoral World. She is married to Edward Mendelson ’66, a professor at Columbia University and poet W. H. Auden’s literary executor.

Cheryl Mendelson ’73 (PhD) knows a thing or two about wedding vows—and not just because she took them twice.

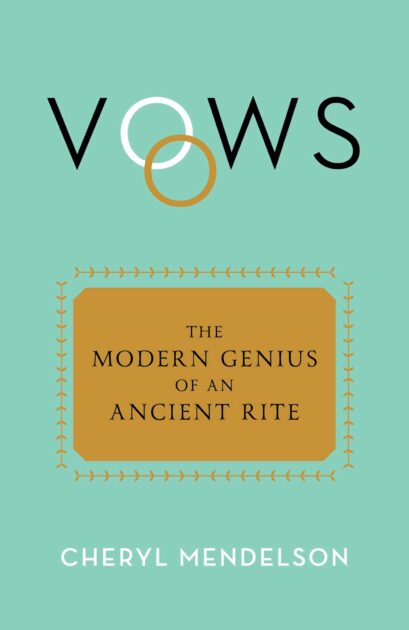

“Wedding vows, if they are from the heart, made before witnesses you respect and care about, are a potent moment in the ceremony. They change things. The tradition draws power from its brevity, its universality, and its great age, wisdom, and beauty. It deserves respect and protection just as great thousand-year-old works of literature, art, and architecture do,” writes Mendelson in her latest book, Vows: The Modern Genius of an Ancient Rite (Simon & Schuster, 2024), which made the Wall Street Journal’s list of 10 best books of 2024.

Publishers Weekly called the memoir of two marriages an “illuminating” meditation on marriage itself that traces the origins of marital vows to today’s widespread global practice, one that cuts across cultural, geographic, racial, economic, and religious divides.

Some, you write, have argued that “all marital vows are at best futile and at worst fraudulent, a tradition that should die.” Why are they wrong?

When someone can’t or doesn’t want to promise their partner to love, keep (protect and support), honor, and be faithful until death parts them, that’s likely a red flag. Marriage means all those things, and most people who marry want to, and do, live by them. Open relationships and friendships may be right for some people, but they’re not what weddings celebrate, and they are notoriously unstable.

“Could I, would I, or should I make these promises to someone?”—you ask rhetorically in your book. What’s the short answer?

There is no short answer. Lucky people have life experiences, from childhood on, that let them understand when they have the kind of feelings that are going to work. Unlucky people like me have to work hard to figure out how to get from being who they are to being someone who could choose a life’s love partner and get it right.

You write that your first, short-lived marriage at age 22 was a mistake, one that you realized as you were exchanging your vows. Apart from your then-husband’s cynicism about marriage and unwillingness to heed his vow of fidelity, you also blame the social context in which you lived.

The divorce epidemic that lasted from the 1960s through around 2010, when the divorce rate began a mostly steady decline, gave the institution of marriage a black eye. It fed suspicion and contempt for marriage that continues today. It justified abandonment of marital norms and rationales for preferring informal cohabitations and open relationships. These dissenting attitudes and their depiction of marriage as an ugly or outmoded way of living continue today in a large minority of the population. They continue to be a powerful undercurrent in modern culture, which still isn’t entirely sure that there is much to admire in marital relations. Vows addresses these currents and makes the argument—a contentious one in today’s world—that being married is a wonderful way of life and the source not just of security and contentment but also of delight and exuberant happiness—for most of us, not all. It’s a reality that is one of the world’s best kept secrets.

For your second marriage, you and your future husband tried to write your own vows. What happened?

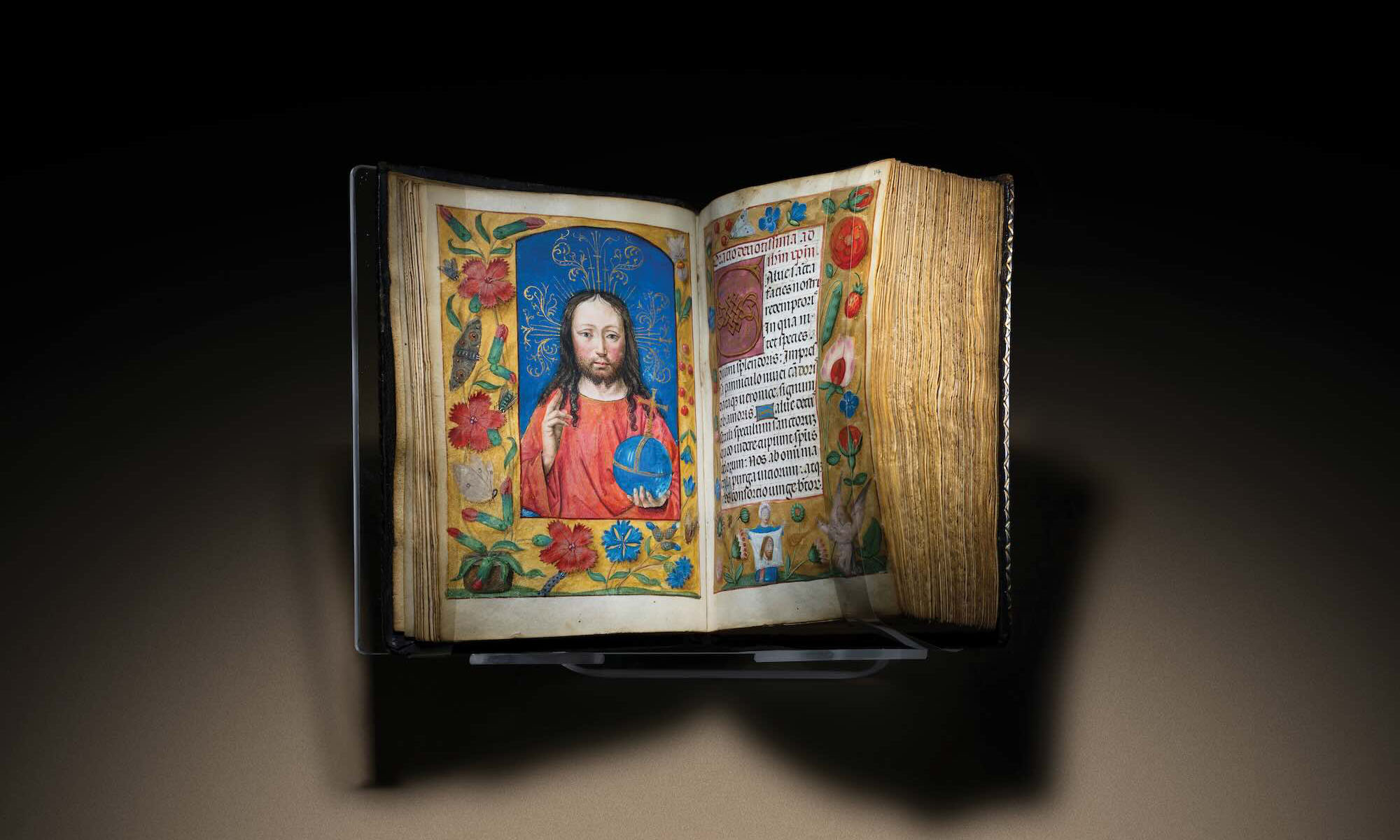

We, a pair of writers, spent many miserable hours trying to write vows and failed. We hated every version we came up with—too sentimental, too private, too cool, too incomplete, and so on. Then my husband, an English professor, opened up the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, which is universally regarded as an English literary masterpiece quite apart from its religious wisdom. Sure enough, it had a wedding ceremony, and, to my surprise, it was the exact one that the judge had read out to my first husband and me years ago. We secularized the Book of Common Prayer version and substituted “you” for “thou,” omitted the woman’s vow to obey, and thought that otherwise it said exactly what we—and most other people—intended and wanted in marriage: to love, honor, keep, and be faithful, no matter what, until death parted us. And, once again, it was a judge who read them at the wedding.

You have called on couples to stop omitting the traditional vows. Why?

People often write their own vows because they aren’t familiar with the tradition and don’t know that as often as not they’re used in a secular style and include no religious references (which may conflict with their own religion or convictions) or calls for women to obey men. Or they believe that they’re outdated, or they are intentionally avoiding the commitment of promises on the typical rationale—“No one can be sure that they will love and be faithful and so on for all their lives.” But that’s just not so. You can’t have absolute certainty, of course, but you can be very sure. And the ancient vows aren’t outdated; they’re timeless and reflect current attitudes comfortably. An informal survey of online self-written vows used in real weddings shows that a majority omitted the vow to be faithful. This reflects no general social tolerance of marital infidelity. A 2022 Gallup poll found that 89 percent of people think infidelity is wrong.

The Roman Catholic Church formally adopted monogamy in 1274 by making marriage a sacrament, even though the idea of monogamy had been part of the Christian Bible for more than 1,200 years. In the book, you argue that the church’s support for monogamy became “the great equalizer.” How so?

Polygyny generally leads to a decrease in women’s freedom, education, and mental and physical health. It also leads to more crime and social instability. Monogamy—real monogamy, not the formal monogamy of the ancient world, in which men had only one wife but sexual access to slaves and concubines as well—is itself a powerful form of equality. It gives everyone a chance to have someone, whereas polygyny lets some powerful men take so many wives that many others have no wife at all, and plural wives have to share one man. Monogamy is itself a kind of leveling that creates a common ground of shared experience, one that crosses social, sexual, and racial lines in the most important parts of life, while polygamy does the opposite.

Rush Rhees Library makes a cameo appearance in your book. What do you remember about your time at Rochester in the early 1970s?

I remember a staggeringly bright and engaged set of undergraduates in classes where I was a teaching assistant for the philosophy department. I went on to teach at other major universities, but, speaking honestly, no later experience ever matched this first one.

Do you ever return to Rochester for Meliora Weekend?

Years ago, I returned to visit several times, but life got busy and I eventually fell out of the habit. But my husband and I have gone to a couple of the University’s New York City events.

Promises

Excerpt from Vows: The Modern Genius of an Ancient Rite (Simon & Schuster, 2024) by Cheryl Mendelson. Reprinted with permission.

I LEARNED ABOUT THE INTERSECTION of personal and social realities in promises from a psychoanalyst, who points out that a society cannot function unless its people are able to make and keep promises and regard it as morally wrong to break a promise. Every promise, he explains, involves at least three parties—not only a promisor and a promisee, but also a witness. The witness, who may or may not be a human person and may be physically or symbolically present, represents the social authority that backs the promise. The ability to make a promise rests on the fact that the words “I promise” or “I swear” or “I vow” carry weight, and they carry weight only if the society in which they are uttered grants them weight.

I LEARNED ABOUT THE INTERSECTION of personal and social realities in promises from a psychoanalyst, who points out that a society cannot function unless its people are able to make and keep promises and regard it as morally wrong to break a promise. Every promise, he explains, involves at least three parties—not only a promisor and a promisee, but also a witness. The witness, who may or may not be a human person and may be physically or symbolically present, represents the social authority that backs the promise. The ability to make a promise rests on the fact that the words “I promise” or “I swear” or “I vow” carry weight, and they carry weight only if the society in which they are uttered grants them weight.

When society doesn’t back promises, promisors can’t get promisees to trust them and promisees can’t rely on the world to see that they have been wronged if their promisor breaches. The third-party witness represents the social force of the promise—the fact that not only this promisee but other people generally will hold a person to their word whether by light or informal sanctions (distrust, frowns, dislike), or serious ones (complete ostracism), or heavy, extreme ones (damages in a lawsuit or prison for major fraudsters). A serious or solemn promise is a little piece of social capital that can be squandered or saved. . . . Apply these thoughts to the realm of love and marriage and you see how, in some important ways, today’s lovers have a harder row to hoe than ever before in history.

In everyday life, in dealings with families, friends, and casual business contacts, the social demand to keep promises is witnessed mostly internally—by the promisor’s own conscience, the internalized voice of the social moral demands. Someone may act on that internal social voice by promising “on my honor” or on my heart or soul or life—or they might say, as children used to, “cross my heart and hope to die.” Shaking hands or placing the hand on the heart have the same force. The call on the witness shows that the words are more than a mere statement of present intent. This is important because there is a large gray area between announcing intentions and making true promises. A witness creates more confidence in the promise and more motivation to keep it. The witness, [says the psychoanalyst mentioned above], becomes “a helper to keep the promise, or . . . an enforcer of it.” In the Middle Ages, when vassals swore fealty with their hands on a relic of the saints, the relic served to call on holy and divine witnesses to back this especially solemn promise.

Many states require witnesses to be present at a couple’s marriage. Custom expects a couple’s friends, relatives, mentors, and often their coworkers and colleagues to attend their weddings, though few people now realize that they, too, are there to witness. . . . Today, two people who take marriage vows may well have no serious witness—no “helper to keep the promise”—and, socially speaking, the vows likely are featherweight.

I am reminded of an early quarrel in my first marriage, conducted in whispers on the stairs of a high floor of the [Rush Rhees Library] stacks. (We were immature but not inconsiderate; we respected libraries’ quiet.) The quarrel ended with my dramatically pulling off my wedding ring and flinging it down the open, winding stairway, which was at least eight stories high. Then we made up and urgently searched the staircase for the ring. A student going up as we came down paused and, helpfully, bent over to look with us. “What are we looking for?” he asked. When we told him, “A wedding ring,” he pulled up and said, “Sure you want to find it?” and climbed on. The message couldn’t have been clearer. When the entire larger society gives all couples that message, they are all on their own, their word backed up only by their own consciences, and their consciences, too, meeting with a good deal of social indifference. Moral and emotional confusion are often the result.

Confusion also results from entirely personal causes. Promises are psychologically complicated. A promise is what philosophers call a “speech act” or a “performative utterance.” How do you bind yourself to keep a secret? Simply by saying, “I promise I won’t tell.” Saying the word “promise” makes it a promise—like magic—like saying “abracadabra” and making a rabbit hop out of an empty hat. A promise exists close to the line between reality and fantasy, or between reality-oriented thinking and the kind of thinking that dominates in dreams and psychosis. This makes some people vulnerable, in promise-making, to confusions of word and deed, of thought and reality, and to infection by neuroticism. Their romantic and marital relations fall prey in familiar ways to their general problem with promising.

The most obvious cases of slightly crazy promises are the childish ones that some adults repeatedly make, then break. The spendthrift buyer, who has broken many promises to control their spending, sincerely promises anew, then sets out for the mall with their credit card smoldering in their wallet. . . . Some types of serial adulterers and alcoholics seem to fit this mold.

On the other side of the coin, there are people who insist on keeping promises even when doing so is a kind of madness—as though they had no power to undo the “magic” connection between word and deed. . . . The most common kind of neurotic reaction to the promises of marriage, however, is the one that scores of books and agony aunts have made familiar. . . . Some people react to their own marriage vows as yokes, traps, prisons, or threats to their independence or autonomy, and experience them as imposed by forces other than their own will. . . . They may attempt to test the “bonds” of their promises by measuring and comparing the marriage to see whether it is still good enough to stick with. In effect, they feel compelled to bring the marriage license up for renewal several times a year; it is never a done deal. . . . [Some people] move in with a lover and cohabit for years, seemingly contented—until they get married. Then everything goes haywire. . . . Naturally, their partner then begs for assurances—promises—and that demand, of course, only intensifies the other’s ambivalence.

Love skeptics often argue that marriage vows are impossible for mature adults in much the same way that a promise to become a cardiologist is impossible for a five-year-old. They say that no one can really know whether love will last for twenty, thirty, or more years; nor can anyone predict whether they would resist extramarital love if love for a spouse waned (or even if it didn’t). Who can ever be sure that the powerful sexual drive will not suddenly break loose from the marriage bonds? . . . You can’t seriously promise that your future unknown self will love that future stranger, so no one can really promise lifelong love and fidelity. All marital vows—so the argument goes—are at best futile and at worst fraudulent, a tradition that should die.

But there are good answers to these arguments. As for that future “stranger” we are supposed to find ourselves married to, most people who marry in their midtwenties or later will tell you, decades on, that with all the changes of age and experience, the spouse is still the same person, not a stranger at all, just as they themselves are, though changed and matured. In crucial ways, adults control who they become as they age. Control over what we will do and who we will be in the far future is a type of freedom that comes with the growth of adult capacities. . . .

We have excellent empirical evidence that young adults are actually very good at predicting their future marital affection so long as they are not too youthful when they marry. Most people who marry between their midtwenties and early thirties don’t divorce, especially if they were raised in intact families, finished college, or have a good job. But couples don’t marry on the basis of a statistical safe bet; they marry on the basis of justified trust in their feelings and themselves. . . . When people love in the way that ordinary, loving husbands and wives love each other, they know more or less intuitively that love like theirs is permanent simply because it’s that kind of love. They recognize that it’s like other permanent loves in their lives. And what if they have no such loves? Then—in one of life’s bitterest injustices—their choice of a life’s mate is more likely to go wrong. Having loved and been loved is how we learn to love and to recognize when we love and when we are loved, and what that means. Those of us who were shorted in love have to work hard to learn how to do it.

Furthermore, these arguments against the vows don’t take into account one central fact: that the very act of taking marriage vows in a ceremony has a powerful psychological effect. For people who can take vows seriously, the near prospect of actually taking vows, witnessed by all the people who matter most to them, creates a dramatic, emotion-charged public moment. It sets in motion a process of psychological reorganization, subterranean, unconscious changes that people resort to poetry to describe—becoming one flesh or half one’s soul and the like. . . .

In a traditional ceremony, unless one or both of the couple are ducking the meaning of their words, the presence of witnesses, representing social conscience and social backing—the third party—makes them feel the vows as a serious undertaking, which, in turn, helps to set in motion these powerful internal processes—and the wedding actually helps to marry them emotionally as well as legally. And, for what it’s worth, our social scientists have often been curious about whether promises really do make any difference—especially promises in public. Their studies show that making public promises actually does result in a higher level of doing what’s promised—much higher in some cases. . . . Two people whose sense of self and self-control reaches into the future will find warmth and comfort in the prospect of loving each other until death parts them. For wedding vows to fulfill their purpose, the ability to take pleasure in an imagined shared future life is indispensable. Vows are an ancient and still powerful means to take control of time.

A version of this story appears in the spring 2025 issue of Rochester Review, the magazine of the University of Rochester.