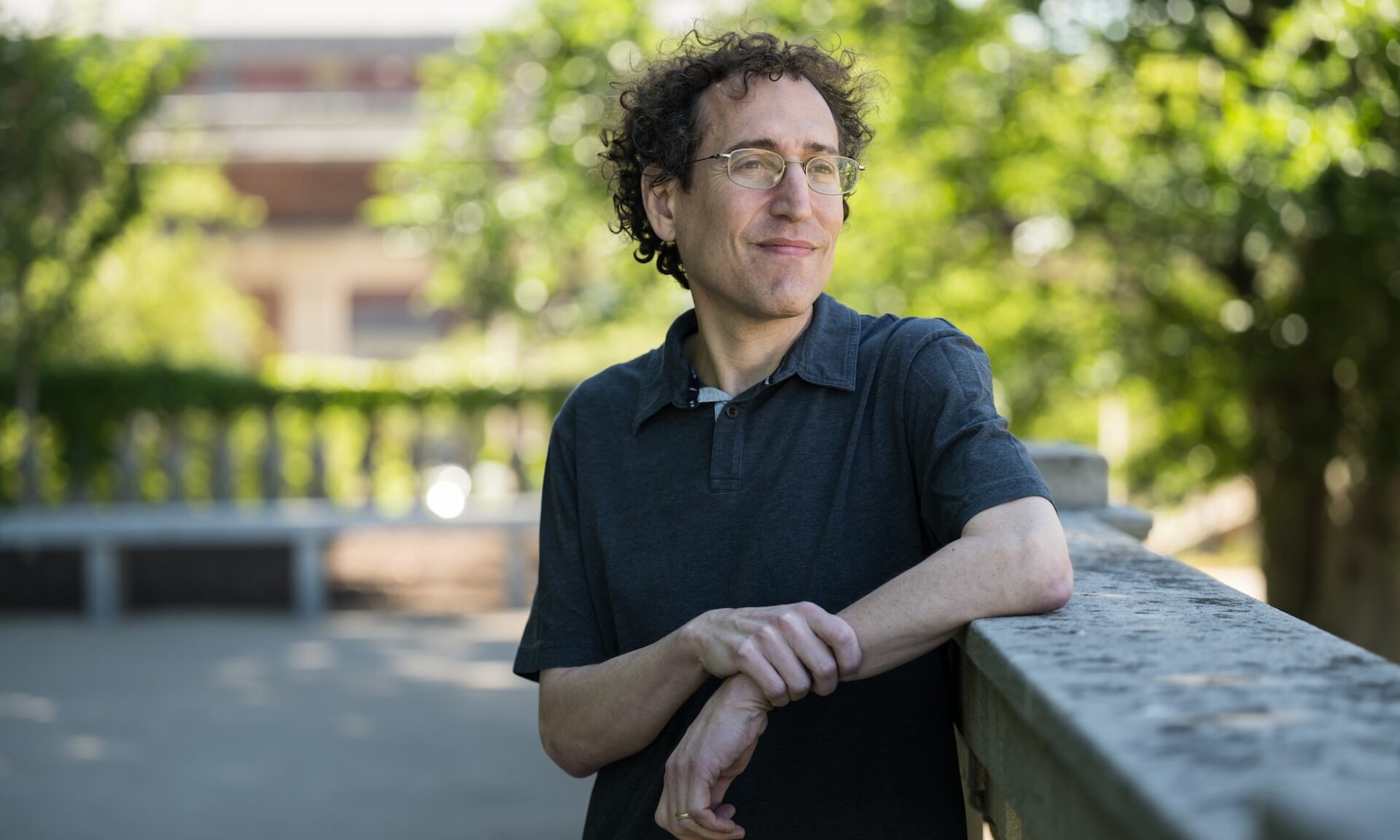

As the 2024 election season heats up, James Druckman, a renowned expert on political polarization, is as busy as he’s ever been.

If you follow the social science driving public policy and political behavior in the United States, chances are you know the name James Druckman.

It’s not an overstatement to call Druckman, who in January joined the Department of Political Science after 19 years at Northwestern University, a star in his field.

But even if you are among the millions of Americans who pay little attention to the theory and practice of government and politics, chances are you have been influenced in some way by Druckman, or at least his work. And if not, you’re about to be.

Listen to “Taking the Temperature of American Democracy”, an interview with Jamie Druckman in which he discusses political polarization, the roles of elites in maintaining—or weakening—US democracy, and the effect of moralizing language on political discourse. Read the transcript.

That’s because Druckman, the Martin Brewer Anderson Professor of Political Science, is fast emerging as one of the nation’s foremost scholars on political polarization and a go-to source for news outlets around the world for the implications of such divisions. Last year, the veteran political commentator and New York Times contributor Thomas Edsall referred to him as among the political scientists “working on getting us to hate each other less.”

“I’m comfortable doing it and I’ll do it when I’m asked but I don’t seek it,” Druckman says of the media attention around his work. “I do think it’s part of one’s job, especially when you’re a political scientist in an election year.”

As of late, Druckman’s research has focused on what he and other political scientists call “affective polarization”—a melding of political and social identities among partisans that leads them to dislike, distrust, and downright disdain members of the other party.

His timing could not be better. The only thing Americans can seem to agree on nowadays is that we are living in an era of extreme political polarization, and that the divisions and disagreements between us have grown personal. Indeed, a Pew Research Center survey recently found that most enrolled Democrat and Republicans use words like “immoral,” “dishonest,” and “unintelligent” to describe their counterparts on the other side of the aisle. Most Republicans surveyed called Democrats “lazy.”

“I think that is something to be fearful of, the normalization of what can devolve into dehumanizing, inciting rhetoric,” Druckman says. “It has consequences for what people think of other groups. It has consequences for what people think of democracy.”

When polarization matters

He spoke from his sparsely decorated office on the third floor of Harkness Hall that was imbued with the controlled chaos of its resident still moving in. Mounds of books here. Piles of papers there. Unpacked boxes lined the walls.

Druckman acknowledges that he might never get around to tidying up. For him, settling in means working, and there is plenty of work to do. There are students to teach, research to complete, and invitations to lecture from around the country to answer.

Then there are requests from news reporters who want him to explain how the political animus came to be and what it means for the American way of life.

Some of the answers to those questions are detailed in a new book Druckman co-wrote called Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and When They Matter (University of Chicago Press, 2024), which explores to what extent partisan hostility degrades democratic institutions and functions.

Published in June, the book and its findings are poised to be talking points for political pundits and everyday Americans alike as the presidential election season—and the partisan rhetoric that comes with it—ramps up this fall.

“Jamie has this amazing ability to connect big, broad questions to people’s daily interactions with politics,” says Yanna Krupnikov, a professor of communication and media at the University of Michigan and one of Druckman’s coauthors. “It is, honestly, difficult to express how much of an important influence Jamie has had on American politics research.”

So, what does the rampant political animus mean for American democracy? The book offers good news and bad news.

Here’s the good news: partisan animosity shapes attitudes and behaviors and politics, but extreme animosity does not invariably lead to democratic erosion. Here’s the bad news: it could.

In the end, Druckman and his co-authors conclude that while partisan hostility has degraded American politics, it is not an existential threat to democracy. The future of democracy, they write, hinges on how politicians behave rather than voters.

The authors cite research that suggests elected officials who act undemocratically—that is, undoing or undermining democratic institutions and norms for their own gains or those of their party and partisans—can slowly shift the idea of what is “democratic” for partisans, the most extreme of whom fail to see the consequences of undemocratic behavior.

“Partisans tolerate the undemocratic behavior of a few elites and then, over time, the system gradually erodes,” the authors write.

Potentially worrisome is that the politicians of tomorrow are the electorate of today, and voters in growing numbers have come of age in an era of extreme partisanship.

Indeed, the book opens with a recap of the fractious 2000 presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore, which was settled by a divided United States Supreme Court, as a harbinger of things to come.

“At the time, that seemed like an explosive political contestation,” Druckman says. “Today that seems rather mundane.

“Now, you’re seeing a cohort coming of age right now, people under the age of 30, who are much more polarized than any prior cohort,” Druckman continues. “I think part of that is they have been socialized in era of extreme acrimony. . . . What that means for what politics will look like as that generation becomes political leaders will be interesting and is a bit worrisome.”

Research that resonates

Druckman, 53, has the pedigree of an academic (his father, Daniel Druckman, was a social scientist), but the reputation he enjoys today took decades to cultivate.

He grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C., where his father consulted for various agencies, including the National Academy of Sciences, before entering academia later in life.

Druckman earned his bachelor’s degree at Northwestern in 1993 and received his doctorate from the University of California, San Diego in 1999. From there, he found work as an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota before returning to his alma mater at Northwestern, where he became a celebrated and beloved professor.

Along the way to Rochester, he authored nearly 200 articles and book chapters. He co-authored or edited several books, including the influential Experimental Thinking: A Primer on Social Science Experiments (Cambridge University Press, 2022), which is considered essential reading by his contemporaries. His work has been recognized by numerous foundations that are household names—McKnight, Guggenheim, Russell Sage. In recent years, he has crept onto various lists of the country’s leading political scientists.

But it was work he produced with a consortium of other researchers from Harvard University, Northeastern University, and Rutgers University, during the pandemic that transcended the ivory tower and elevated his public profile.

Their research identified links between social behavior and COVID-19 transmission, as well as the impact of messaging and regulation on individuals and communities of people. They explored topics that were in news feeds every day during the health crisis, from social isolation and misinformation to vaccine hesitancy and masking mandates.

Their goal was to help governments make more informed decisions on public policies and allocate resources more effectively.

Suddenly, Druckman, who had been cited as an authority on myriad topics by a handful of news outlets in his career to that point, was everywhere. Google Scholar, for example, shows Druckman’s research has been cited by academics nearly 50,000 times, an extraordinary number by any measure and one that reflects the impact of his work. Well over half of those citations occurred in the last five years.

The consortium, originally called The COVID States Project, has since morphed in name and scope into the much broader Civic Health and Institutions Project, which provides state level data on citizens’ opinions on a wide variety of topics. The project has touched on everything from presidential approval ratings and mental health among young adults to Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter and election fairness.

The Riker legacy

When Druckman announced he was leaving Northwestern for Rochester, word of his departure reverberated through the political science community.

“For Jamie to go anywhere is a massive coup for that university,” says Samara Klar, a professor of political science at the University of Arizona, a former student of Druckman’s at Northwestern, and another of his coauthors. “He’s a giant in our field and surely one of the most influential living political scientists.”

Druckman says his move to Rochester was inspired by two factors.

One was family considerations. His wife, with whom he shares two sons, grew up in the Rochester area. Today, they make their home in Pittsford.

The other was the Department of Political Science’s illustrious history as a trailblazer in the field, as well as the intellectual curiosity and collaboration of its faculty and graduate students that he witnessed after giving a talk at Rochester in 2022.

Druckman cites as one of his greatest influences the late Rochester political scientist William Riker, who revolutionized the field by applying game theory and mathematics to his research and, in the process, transformed the department into a world-class destination for the study of political science.

Riker died in 1993. But the culture he and his colleagues built, Druckman says, still exists.

“It reflects remarkable leadership in the last 30 years years,” he says. “This is palpable on both the individual collegial level and the collective culture of the department.”

Druckman specifically singles out the launch in 2022 of the Democracy Center, led by Gretchen Helmke, the Thomas H. Jackson Distinguished University Professor in political science, as an exciting development. The center seeks to foster a non-partisan community of scholars that advances the study and practice of democracy through research, teaching, and public engagement.

“Every single person I met in the department, faculty and students, had this genuine intellectual curiosity to address important political, social, and economic questions, and they were serious about doing that in a very meticulous and systematic manner,” he says. “That’s a unique intellectual experience in academia. This is a collection of truly special scholars and people.

“It’s the ideal,” he adds. “And, you know, it’s incredibly unique and special. I can’t imagine a better place to be.”

This story appears in the summer 2024 issue of Rochester Review, the magazine of the University of Rochester.