Residuals at Artpark

One of several site-specific works commissioned to be installed at Artpark outside Buffalo, the the Topolskis’ exhibition Residuals is free and open to the public. The exhibition, organized by the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art and the collaboration Resource:Art, Play/Ground, has been reimagined for 2020 as outdoor-only installations. The exhibition ends September 20.

For a decade, beginning in 1974, Artpark, outside Buffalo, was a hotbed of avant-garde art. The experimental program, then owned and operated by New York state, commissioned site-specific works from hundreds of artists and art collectives in the summers through 1984.

Among the participants were the collective Ant Farm, who went on to create the famous installation Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, Texas; visual artist, film director, composer, and musician Laurie Anderson; environmental artist Agnes Denes, among whose later works was Wheatfield: A Confrontation, a two-acre wheatfield that she cultivated and harvested on a landfill near the World Trade Center; and the now renowned glass sculptor Dale Chihuly, creator of the blue and gold glass chandelier that’s the centerpiece of the Wolk Atrium at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music.

Artpark’s first decade was “really rich,” particularly because of the feminist artists who participated and their emphasis on “moving art out of the commercial realm and into the public realm,” says Rochester’s Allen Topolski, an associate professor of art. “Everything that had built up to institutionalize art was being questioned in the 1970s and early ’80s. These artists weren’t interested in being in New York City galleries when they started out—although they eventually ended up there.”

The residency program ended in the 1990s. Today, Artpark is a partnership between New York State Parks and the independent nonprofit Artpark & Company.

But ghostly traces of the residency program remain. The artists lived near the Niagara Gorge, in 11 cottages. The only remnants of the cottages are the concrete slabs on which they stood. Allen and his daughter, artist Aster Topolski, have created a temporary, site-specific artistic installation, titled Residuals, that evokes the residency in its heyday.

In their artwork, each cottage site features a single object associated with domesticity and a fabricated architectural remnant, suggesting a fragment of wall. The Topolskis anticipate that the objects and fragments will act as cues for viewers to construct a narrative of place as they move from slab to slab.

The work is part of this year’s Play/Ground, a platform for site-specific installations by contemporary artists. First created in 2018 by the Buffalo Institute for Contemporary Art and the collaboration Resource:Art, Play/Ground has been reimagined for 2020 as outdoor-only installations in Buffalo that can be experienced in observance of social distancing guidelines. The free, public event runs from September 11 to 20.

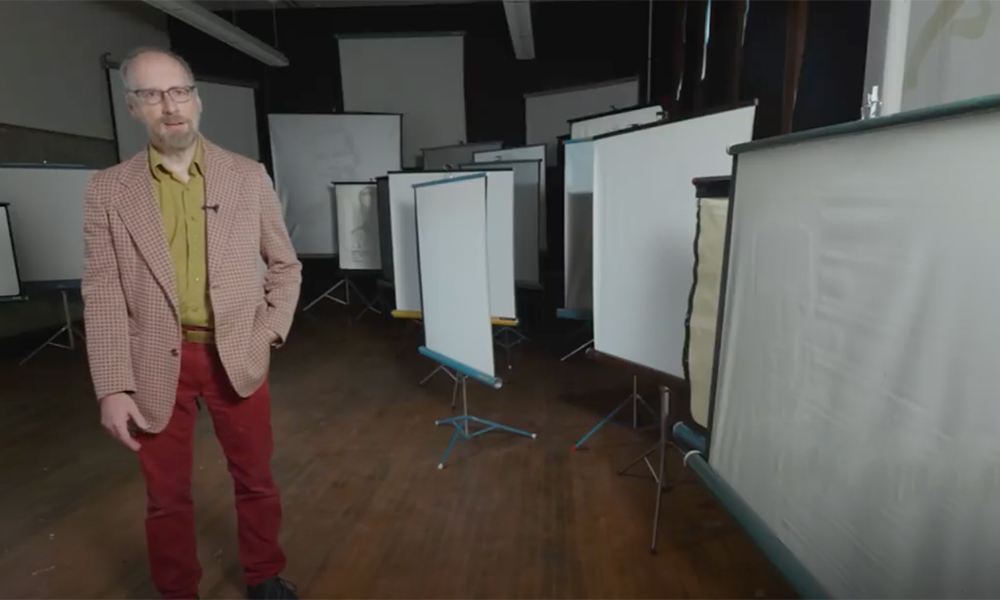

Allen Topolski’s work is concerned with nostalgia and memory in technologies of domesticity and convenience. “It’s metaphorically an attempt to bridge my domestic life and my creative life,” he says. He asked Aster to collaborate with him on the project because “I realized this site we were addressing was grounded in a history that parallels my relationship to her. I think about a passing down of information. Much of what we do conceptually has been allowed by many of the artists that we’re addressing in the installation.”

Aster, who will work begin work on an MFA at the California College of the Arts next year, returned from Miami to Rochester in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. She says the installation is, in part, “a representation of valuing the moment and the spaces we’ve created for ourselves and freezing it in time—freezing a moment we may not recognize the full value of until later.”

Says Allen: “What’s interesting about the work is how we continually find connections between things that we’ve done, and they’re substantiated somehow through the existence of the work of the artists who were there.

“We’re enjoying the intersections that occur: mine and hers, ours and theirs, then and now. That’s what site specificity is about. It’s about understanding where you are through understanding what was there before you.”

Read more

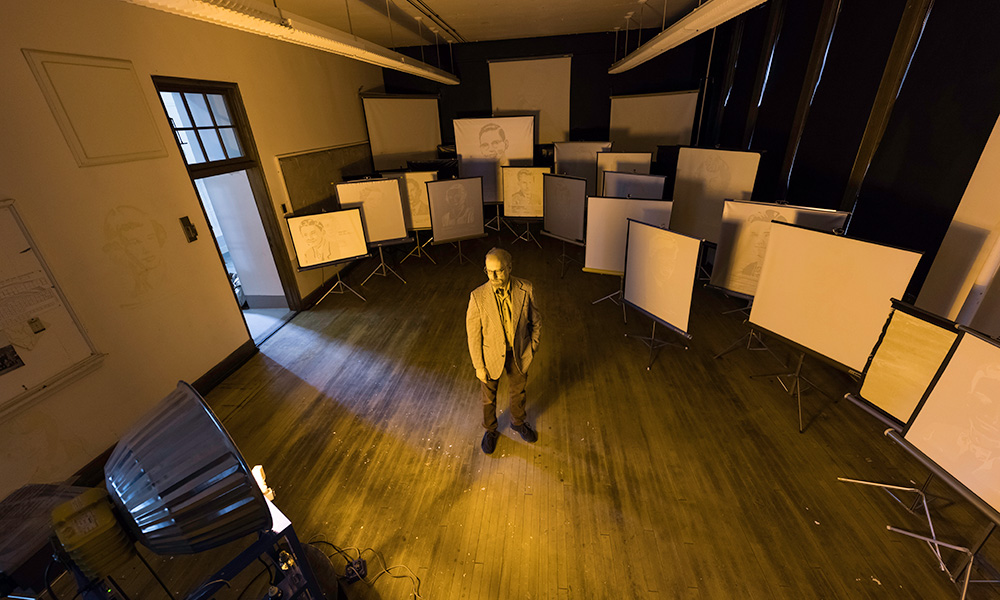

A Playground for Artists

A Playground for ArtistsIt once stood as a school, where students walked the hallways, and learned the periodic tables inside its classrooms. Nearly a century after its construction, and decades since it has been a school, the old Medina High School became a playground of sorts.

Empty high school becomes a playground for artists exploring memory, nostalgia

An empty, Victorian-era building in Medina, New York, hosted a 2018 collaborative art project inspired by the fleetingness and permanence of memory.