It was 100 years ago in May, shortly after the United States entered World War I, that President Woodrow Wilson signed the Selective Service Act, authorizing the government to raise an army through conscription. The draft was instrumental in raising troops to fight both world wars, as well as the Korean War. It was generally accepted, too—until the mid-to-late 1960s, at the height of the unpopular Vietnam War.

When President Richard Nixon ended the draft in 1973, he did so with the help of a roster of University of Rochester faculty and administrators.

LISTEN: This week’s University of Rochester QuadCast discusses the team of faculty and graduate students who helped end the military draft.

Podcast transcript

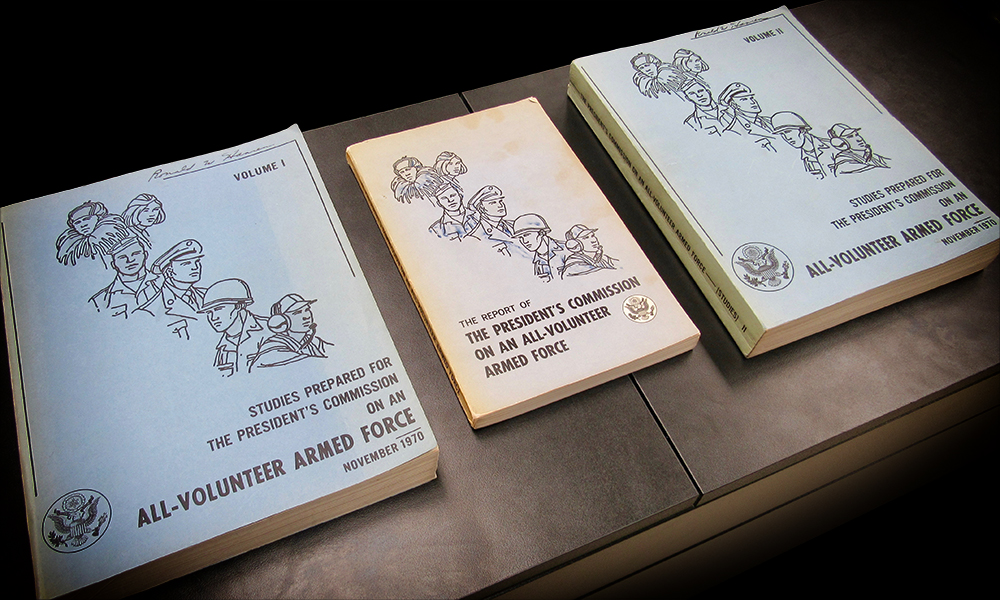

In 1969, President Richard Nixon formed the President’s Commission on an All-Volunteer Armed Force and named Thomas Gates, the secretary of defense under former President Dwight Eisenhower, as its chair. There was a notable presence of University of Rochester faculty and administrators either on the commission, or prominent on its staff. Then President W. Allen Wallis, an economist and statistician, was among the 15 members of the commission. William Meckling, dean of the Graduate School of Management (later to become the Simon Business School), served as the executive director of the commission staff, which included Walter Oi, who had joined Rochester’s economics department two years earlier.

And there was Ron Hansen, professor emeritus and former senior associate dean for faculty and research at the Simon Business School, serving as a researcher.

Hansen—the only surviving member of this group—was working on his graduate thesis in economics at the University of Chicago when he was invited to join the commission staff. The invitation came from his thesis advisor, Larry Sjaastad, who also served on the staff. It was an invitation that was too good for a graduate student to pass up.

“Having Congress accept an all-volunteer army was going to be a hard sell, since it would require a large increase in the federal budget,” Hansen says. “That made my work with the commission an exciting opportunity.”

The argument that Wallis, Meckling, and Oi helped shape—along with University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman and others—had little to do with the popularity of the draft; it was rooted instead in labor economics.

As Hansen—and many other economists—sees it, a milestone in the movement to end conscription came during a conference on the draft held at the University of Chicago in 1966. That’s when Walter Oi delivered a paper on the budgetary cost of eliminating the draft in favor of an all-volunteer military.

“This was not an academic exercise on the workings of free markets,” says his widow, Marjorie Oi. “Walter really thought the draft was immoral, inequitable, and inefficient.”

Oi detailed the social and hidden costs of conscription, and argued that a higher salary for enlistees would increase retention, allowing for an overall reduction in total staff due to a reduced need to train personnel.

“A poll taken before the conference showed that most attendees favored the draft,” recalls Hansen. “But the results were flipped in a poll taken after the conference. Oi’s paper made the difference.”

QUADCAST SUPPLEMENTAL: Listen to the full interview with Ronald Hanson.

When Nixon formed the Gates Commission, Wallis, Meckling, and Oi picked up where Oi’s 1966 paper had left off. The commission cast conscription as a labor issue since it involved raising a military with people—the labor force. “But the military’s budget was not representative of the true value of its resources,” Hansen explains. “Some of that value was taken away from individuals when they were drafted.” That lost value—not seen on any budget line—amounted to a conscription tax. In effect, they concluded, a person drafted into the military was paying a tax equal to what he (and they were all men at the time) would have received if he volunteered.

“Some people in the military at the time had very high wages in civilian life, while others did not. As a result, the tax varied greatly among the personnel,” Hansen says. “My job was to come up with a distribution that took all of that into account.”

Hansen contends that having members of Congress understand the true costs associated with conscription helped convince them to accept the president’s proposal to adopt an all-volunteer military.

At the same time, his work on the commission served another, more personal purpose; it brought him to Rochester.

“I worked directly with several people from Rochester while doing commission work and developed a great deal of respect for them,” he says. “When Meckling asked me a few years later to join the faculty at the business school, I had no hesitations.”

Hansen joined the Rochester faculty in 1971 as an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Management, a predecessor of the Simon Business School of Business. He left the University in 1986 to become an associate professor at Ohio State University, only to return to Rochester two years later as the associate dean for academic affairs. He became the senior associate dean for program development and the William H. Meckling Professor of Business Administration in 2009 and retired from the University in September 2016.

“I’m satisfied that our work has stood the test of time,” he says of the Gates Commission. “Yes, sometimes recruitment goals were missed, but on balance, the personnel objectives of the military have been fulfilled.”