The large disparity in state revenue collection between the West and the rest of the world didn’t happen until the 20th century—much later than commonly thought.

In 2015, two political scientists at the University of Rochester began assembling data to study the effects of colonialism on the ability of newly liberated states to collect revenues after independence.

Answering the question required information on former Western colonial powers as well as non-Western states, among them the former colonies. The scholars—Alexander Lee, an associate professor in Rochester’s Department of Political Science, and Jack Paine, now an associate professor of political science at Emory University—amassed a trove of data from 18 Western countries and 76 non-Western countries, with data points spanning the 19th to the 21st century.

What they found was so surprising that they worried they’d gotten it wrong. Their results ran counter to conventional wisdom.

“Wow,” Lee remembers thinking.

Data reveal an overlooked pattern

Academic research on state revenues seems to have overgeneralized the example of Britain, which developed the capacity to efficiently collect revenues as early as the 1700s, and throughout the 19th century. Britain had a strong need to raise revenues during the Napoleonic Wars, from 1803 to 1815. Britain was also where industrialization first took root. Based on the British example, scholars generally assumed that Western European nations, also affected by the Napoleonic Wars, followed a similar path as they, too, underwent economic modernization.

But that seems to have been a mistake. Britain wasn’t a trailblazer. Instead, it was an outlier. Existing studies showing an early European advantage in revenue collection are largely based on “little bits and pieces of revenue estimates with unrepresentative data points,” says Paine.

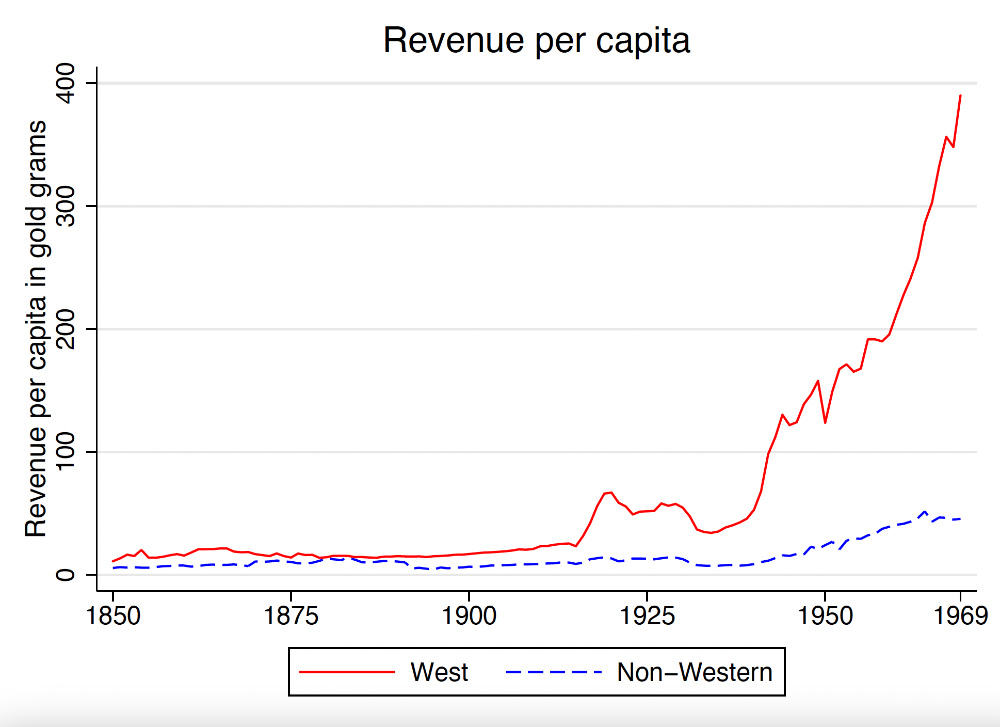

The two scholars had stumbled on a previously overlooked empirical pattern in state revenue collection. As it turns out, as late as 1913 central governments in the West collected very similar levels of per capita revenue as the rest of the world—notwithstanding the fact that many countries in Europe already had the necessary infrastructure in place that would have allowed for much greater revenue extraction.

“People just implicitly assume that if European countries had the ability to raise taxes, they were probably doing it,” says Paine.

In their resulting paper, “The Great Revenue Divergence,” published in the journal International Organization, the coauthors demonstrate that central governments in the West and the rest of the world did not differ dramatically in their ability to raise revenues, measured per capita, until the eve of the First World War. That’s “despite ruling richer societies and experiencing a long history of fiscal innovation,” they write. And while many Asian and African countries and colonies lagged behind Europe in revenue collection, these differences were still small compared to 20th-century standards.

In 1913, for example, Chile and Uruguay each collected more revenue per capita than any country in Western Europe. Denmark—now well known as a high-taxation state—collected less revenue than either Trinidad and Tobago, South Africa, Malaysia, Cuba, or Panama. The United States raised even less than any of these countries, coming in just slightly ahead of Jamaica.

The beginning of the great revenue gap

It wasn’t until the first half of the 20th century—much later than commonly thought—that the differences grew large. By the time the Second World War began, the schism between the West and the rest of the world had become a whopping gap—what the authors call the “20th-century great revenue divergence.”

And the gap has continued to grow. Between 2010 and 2019, for example, Western states raised on average 43 percent of their annual GDP in government revenues, compared to just 27 percent in non-Western countries. According to Lee and Paine, disparities in per capita revenue intake were even greater, given the much higher income levels in the West compared to much of the rest of the world. Some East Asian states, particularly Japan, are exceptions, with a history of efficient bureaucracies that allowed for large taxation increases, similar to was happening in the West.

What changed in the 20th century?

Two things—need and ability. Paine and Lee argue that high levels of revenue intake require both a high demand for an active government that can supply public services to its populace and a high level of bureaucratic ability—also referred to as fiscal capacity. In other words, taxation (and general revenue extraction) requires both strong institutions and robust societal demand, they argue. Ultimately, a system of taxation and revenue collection can only work in an environment where the state possesses enough data about its population to know from whom it can collect and exactly how much. At the same time, the political will to tax heavily is vital, coupled with the population’s demand for increased state services, the duo says.

For example, in 19th-century Denmark, Lee notes, the state knew a lot about its people, but Denmark didn’t really use that information fiscally. Why? Because there was no need. Denmark wasn’t fighting wars and didn’t yet have a welfare state.

The effect of war on revenue collection

Of course, war doesn’t make revenue extraction any easier, but “it drastically increases a state’s incentive to do it,” says Lee. The First World War generated an extraordinary demand for revenues to pay for weapons. But the West’s higher level of revenue extraction continued after the war, and the great revenue divergence that began during World War I widened explosively after the Second World War.

Before the 20th century, the rule of thumb had been that a government would decrease its revenue intake once a war was over. But a few factors changed Western states’ behaviors after the First World War and made the higher level of revenue extraction permanent: there was considerable war debt to pay off, the voting franchise expanded, allowing more people to vote, and Western incomes grew dramatically—all of which went hand in hand with the onset of the modern welfare state.

“The wars are front and center in terms of creating high societal demand for greater revenues and taxation,” Paine says.

Does higher taxation equal greater political stability?

Generally, tax collection and a country’s fiscal capacity are strongly associated with economic development, political order, and governance quality—affecting such critical needs as drinking water, hospitals, road systems, public schooling, and military preparedness. In turn, the quality of these assets has a direct bearing on human welfare and long-term economic growth.

But, as Lee and Paine caution, that doesn’t mean greater revenue collection necessarily leads to greater political stability. In principle, according to Paine, a nefarious government could use a capable tax system to exploit its population, which would likely trigger internal conflict and, thus, destabilize the country.

Yet in Western countries with relatively strong constraints on the executive branch, it’s generally true, says Paine, that a state’s ability to efficiently tax and extract revenues “is good for political order.”

Read more

What can trigger violence in postcolonial Africa?

What can trigger violence in postcolonial Africa?

Why have civil wars and insurgencies occurred in Sudan and Uganda, but not Kenya? A study finds the origins of ethnic violence in precolonial political organization.

Are political parties getting in the way of our well-being?

Are political parties getting in the way of our well-being?

On the contrary, a historical state-level analysis links party competition to increased public investment and greater social well-being.

US state spending historically biased against immigrant, nonwhite communities

US state spending historically biased against immigrant, nonwhite communities

Scholars show a “direct link” from the 1920s to the early 1960s between the race, class, and immigration status of constituents and their district’s share of state funds.