A remarkable collection acquired by the University of Rochester’s Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), is now fully digitized and open to scholars.

Find it online

Want to experience Charlotte Perkins Gilman up close and personal? The entire collection has been digitized. The finding aid for the collection is the first one in the RBSCP’s history to incorporate digital objects, an undertaking spearheaded by the libraries’ ArchivesSpace team of Miranda Mims, Jeff Suszczynski, Esther Arnold, and Marcy Strong.

“The idea was to be able to integrate the libraries’ ever-growing, freely accessible, digital collection of documents, photographs, and audiovisual materials into the finding aids,” explains Mims, special collections archivist for discovery and access at the RBSCP. “These aids detail pertinent information about manuscripts and archival material, and are the essential discovery tools that guide researchers through specific collections.”

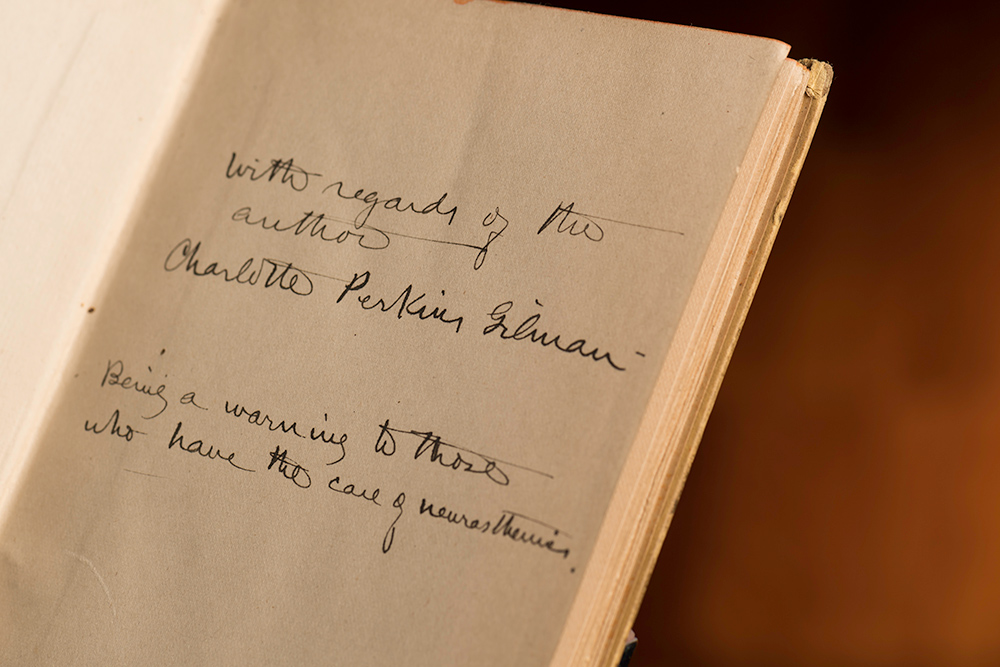

Feminist author and social reformer Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935) was well known in her day, then largely forgotten until modern scholars generated renewed interest in the woman who is perhaps best known as the author of the short story The Yellow Wallpaper (1892). The acquisition, made by the RBSCP in 2017 with the support of the Friends of the University of Rochester Libraries, consists of 52 personal letters from the 1880s. Around the same time, the RBSCP also purchased an inscribed first edition of The Yellow Wallpaper.

Among those celebrating the acquisition is Brianna Theobald, an assistant professor of history at Rochester, who specializes in American women’s history and is planning a course on Gilman.

“Gilman’s writing is significant for the bold utopian futures she imagined,” says Theobald, referencing other famous works by Gilman, such as Women and Economics (1898) and Herland (1915). “She advocated women’s economic independence and believed that women’s maternal instincts, once liberated from the confines of the nuclear household, could transform the world.”

Jessica Lacher-Feldman, assistant dean and Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, sought the Gilman collection to add to the RBSCP’s already rich holdings in related areas.

“Because of our strengths in women’s history and women’s rights, her letters seemed like a natural addition to the collection,” says Lacher-Feldman.

Gilman was part of a well-known literary and suffragist family. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, the original Charlotte Anna Perkins was the daughter of Frederick Beecher Perkins and Mary Anna Fitch Westcott.

“We acquired the letters not long after getting the Isabella Beecher Hooker papers. Charlotte happens to be Isabella’s grand-niece, the granddaughter of her sister, Mary,” says Lacher-Feldman.“It was Isabella who paid for Charlotte’s college education.”

Gilman had one brother, Thomas Adie, two years her senior. The family moved frequently after Frederick Perkins abandoned them in 1867. After her father left, her aunts played a critical role in helping the family.

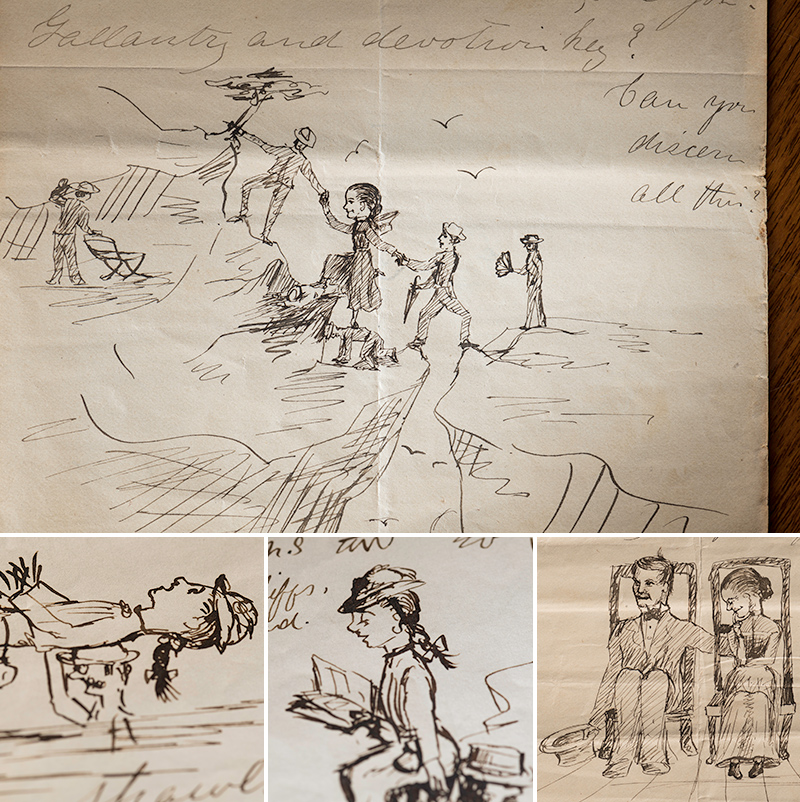

Growing up in relative poverty, she had an irregular formal education, but developed her artistic skills at the Rhode Island School of Design where she took classes for a year. Afterwards Gilman found sporadic employment as an art teacher and illustrator.

Arguably her most famous work, The Yellow Wallpaper is told by a female first-person narrator who is suffering from postpartum depression. The central character is longing to write and return to her work but is told by her physician husband, as well as other men around her, to abandon all creative undertakings, and instead rest at a rented colonial mansion, mostly inside a nursery with peeling yellow wallpaper.

What adds to the eeriness of Gilman’s storytelling is the backdrop against which she wrote. In 1885, shortly after the birth of her only child, Katherine, Gilman herself sank into what’s now recognized as a postpartum psychosis, a fact she alludes to in the inscription of the Rochester first edition: “Being a warning to those who have the care of neurasthenics,” a term used as early as 1829 to describe those suffering from a condition that manifests itself in anxiety, fatigue, high blood pressure, heart palpitations, and depressed mood.

We know many of the emotional details of her despair through the personal letters in the recent acquisition, the bulk of which are made up of Gilman’s correspondence to her close friend, Martha Allen Luther Lane, during the period of 1882 to 1889. In her letters to Lane, often spaced barely two days apart, she minces no words when it comes to her work, marriage, motherhood, and depression.

“Her descriptions of her experience with depression are so raw, succinct, and vivid,” says Andrea Reithmayr, special collections librarian for research and collections, who processed the Gilman acquisition.

In 1884, Gilman married her first husband, the artist Charles Walter Stetson. The pair separated three years after Katherine’s birth and divorced in 1894.

After Katherine’s birth Gilman writes in a letter to Lane on July 8 and 15, 1885, that she’s “very illtempered at times; and almost always morose and melancholy. My very voice changes, and I feel as if I had little option in saying or not saying things.” She assesses her own mental descent as “drifting open eyed into insanity.”

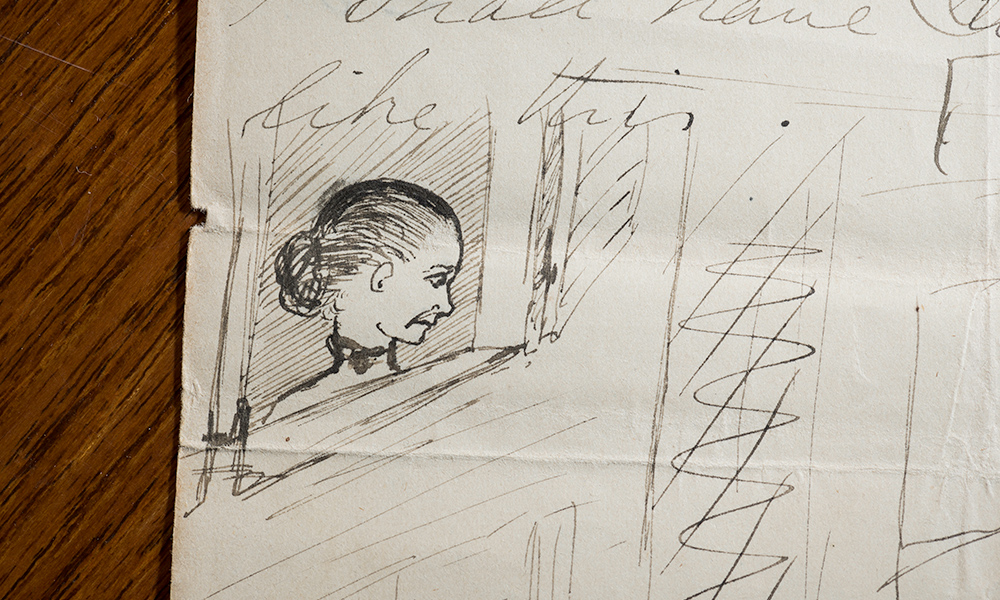

Sometimes Gilman drew scenes, people, and items in her letters. For instance, she sketched a sapling tied down in her August 28, 1895 letter to Lane, describing her feeling trapped in a marriage with an incompatible husband.

(University of Rochester photos / J. Adam Fenster)

According to Reithmayr, the feminist’s writing cuts straight to the core of many women’s struggles in the late 19th century.

“Gilman is so clear that while the love of others is welcome and needed, so, too, is her need to work,” says Reithmayr. Gilman wrote to Lane on August 22, 1885 that she asked her treating physician if he would give up his ambition when he tells Gilman to forgo writing and painting as part of her recovery process. (Ironically, today, people who suffer from depression are often advised by mental health experts to keep a diary.)

“No amount of love can keep me happy while I am hindered from my work…When Dr. Knight spoke in the same way about my present duties and the importance thereof, I admitted all that he said and simply asked him if he would like to give up his business, his education, his ambition, etc. and do the same thing? Being an honest man he laughed and said no.”

A rather different, giddy side to Gilman emerges in her January 24, 1884 letter to Lane in which she mentions recently published work.

“My various ‘poems’ are printed and if you want to buy a ‘Woman’s Journal’ issue of Jan. 12th, you may have the proud joy of seeing my illustrious name therein.”

The University’s collection also contains 15 of Gilman’s advertising trade cards, which she illustrated (unsigned) for several businesses in the Northeast, most notably for the maker of household soap, Kendall Manufacturing Co.

Reading her letters, you can see—almost hear—some of Gilman’s spunk and self-deprecating humor.

“I’m trying to paint lots of cards for Xmas but I don’t get on very fast. Well it’s vacation!,” she tells Lane in a July 21, 1884 letter, shortly after her marriage to Stetson. “Housekeeping flourishes. I kin cook. My appetite fails not. But O my power of writing letters does. I haven’t a word to say to you, dear, so I’ll stop.”

The letters have attracted the attention of researchers such as Todd Gernes, who places them in the context of young women’s literary culture in 19th-century America.

Rochester’s collection “greatly extends and enhances our understanding of how a close, literary friendship that lasted a lifetime provided emotional support and intellectual nourishment to two women of talent and ambition who, though very different in temperament and outlook, strove to engage the world around them in significant ways,” says Gernes, an associate professor of history and American studies at Stonehill College in Massachusetts.

“The rawness, intensity, and dailiness of the letters highlight her strength, vulnerability, and complexity—in a word, her humanity.”