Computer scientist Henry Kautz likens Twitter to a kind of distributed sensor network. Hundreds of millions of tweets are posted to the platform each day, with each user observing and reporting on some aspect of the world.

Unlocking big data

A Newscenter series on how Rochester is using data science to change how we research, how we learn, and how we understand our world.

“Each report is very noisy,” says the Robin and Tim Wentworth Director of the Goergen Institute for Data Science at the University of Rochester. “But the aggregate results can be reliable.”

Those results can provide information to meet all kinds of challenges–from public concerns regarding health, safety, and the environment, to private ones regarding client and customer satisfaction and changing consumer tastes.

Tracking sickness and disease

Kautz and his team have used Twitter to reliably identify and track people with symptoms of flu and food poisoning, enabling health officials to respond much more quickly to disease outbreaks, and even to forecast when and if a specific individual will fall ill.

The Las Vegas Health Department field tested the nEmesis app developed by Kautz and his team to connect food-poisoning-related tweets to restaurants. The researchers found that the tweet-based system led to citations for health violations in 15 percent of inspections, compared to 9 percent using the traditional random system. That resulted in an estimated 9,000 fewer food poisoning incidents and 557 fewer hospitalizations during the course of the study.

Increasing business transparency

Huaxia Rui is a big believer in transparency. That’s why the assistant professor at the Simon Business School uses data science to delve deeply into Twitter–one of the most transparent of our social media– to study the relationships between companies and their customers.

Rui studies how companies respond to tweets, with the goal of increasing transparency about customer satisfaction across multiple industries.

For example, working with Simon professor Abraham Seidmann and PhD student Priyanga Gunarathne, Rui analyzed more than 450,000 Twitter messages to and from three major airlines. The researchers found that all three airlines were more likely to respond to tweets sent by customers with a higher number of followers. The study raises interesting questions about fairness, but also concedes that airlines “may have limited resources to handle all requests for engagement.”

“When you call an airline or any company to complain about it, only you and the company know about it,” Rui says. “If you’re unhappy, what can you do? File a lawsuit? Most people won’t do that.”

Twitter postings, on the other hand, are instantly public. “In general its a good idea to improve the sharing of this data, and increase the transparency, so that people can see in real time what companies are doing and whether their customers are happy,” he says.

Allocating resources

Rui has also found ways in which Twitter data might help both businesses and consumers operate more efficiently.

In one of his first studies involving the social media platform, Rui and two fellow researchers analyzed the impact of four million tweets on box office sales for 63 movies. So-called “intention tweets”–from people who hadn’t seen the movies, but indicated they wanted to–appeared to have a greater effect on box office sales than “positive tweets” from people who had actually seen the movies. Why? Rui cites the dual effect of intention tweets: They are a clear indication that their authors intend to see a movie, and also make their followers aware of the movie, possibly influencing them to see it as well.

How might a savvy business use this kind of information? Imagine you’re the manager of a retail store and it’s two weeks before Black Friday. If you’re scanning Twitter, and detect a surge in “intention” tweets showing an interest in one of your products, “That could be useful for determining your staffing and inventory,” Rui notes.

Geotagged tweets could narrow such staffing and inventory decisions to single regions, even individual stores.

The benefit for consumers? They may be less likely to find long lines or empty shelves on Black Friday if their local stores have done their Twitter “homework” in advance.

Taking the pulse of the voters

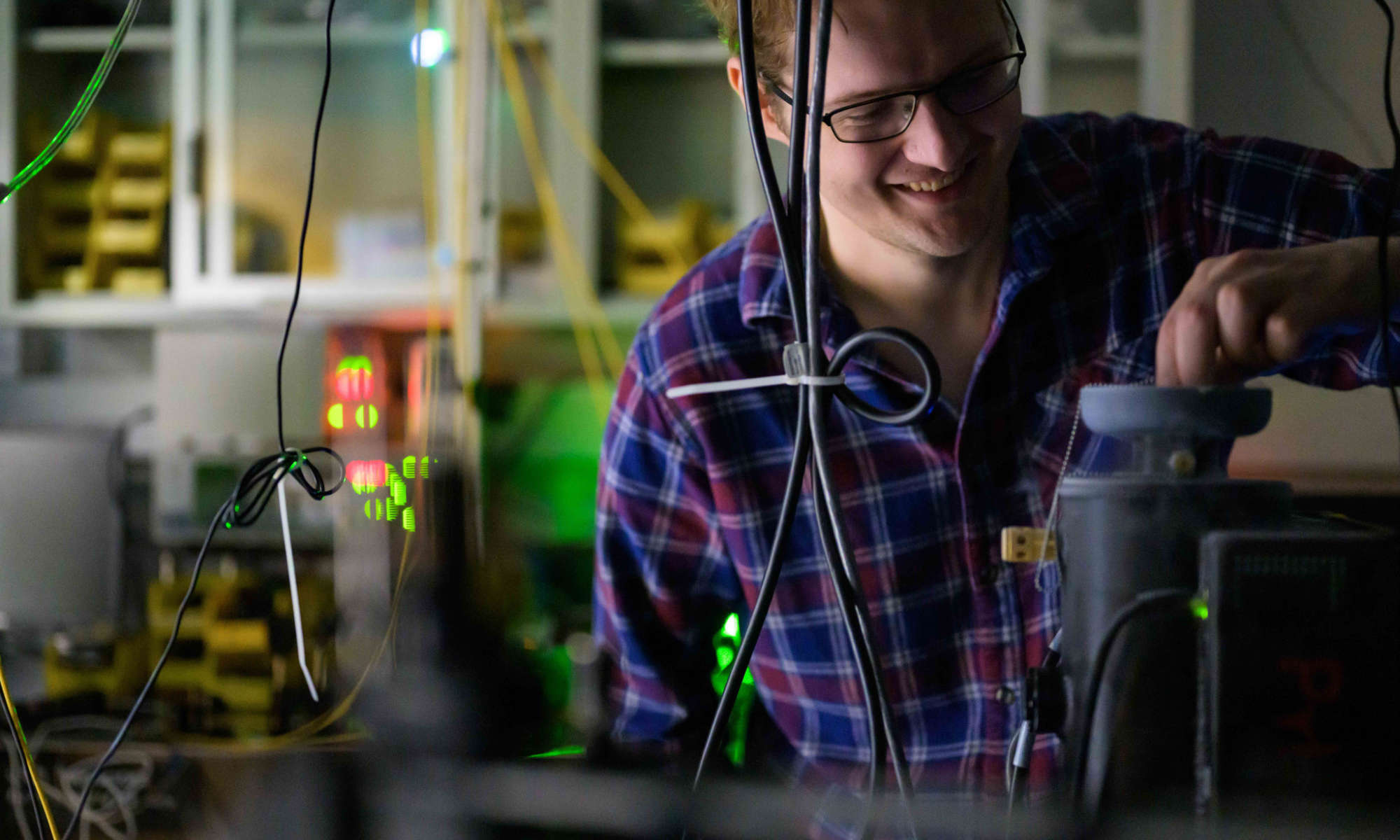

Jiebo Luo, associate professor of computer science, PhD students Yu Wang, and their colleagues tracked the Twitter followers of Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Bernie Sanders and other candidates last year to better understand the dynamics of the 2016 presidential campaign.

“We wanted to understand how each of the candidate’s campaigns evolved, and be able to explain why someone won or lost,” says Luo, an associate professor of computer science.

Though the researchers did not set out to predict who would win the recent presidential election, their exhaustive, 14-month study of each candidate’s Twitter followers–enabled by machine learning and other data science tools–offers tantalizing clues as to why the race turned out the way it did.

In another study with potential political applications, Luo and his students used images extracted from Twitter to train computers to determine what sentiments are likely to be elicited by images.