A war that has targeted Ukrainian heritage has made the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation a cultural refuge.

“A missile. To destroy a museum.”

Even without context, the terse, matter-of-fact delivery of those six words holds a palpable incredulity. So, it may not come as a surprise to learn they were part of a May 7 address given by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, whose country has been the victim of an unconscionable Russian assault since February 24.

Zelensky began his address by delivering the news that the museum and historic home associated with 18th-century Ukrainian philosopher and poet Hryhorii Skovoroda were destroyed overnight.

“As of May 7, the Russian army destroyed or damaged nearly 200 cultural heritage sites already,” reported Zelensky. His calling of attention to what’s being destroyed is more than a matter of accounting; by stressing the extent of Russia’s aggression, Zelensky highlights a less conspicuous target of this war: Ukraine’s identity.

The current threat to Ukrainian culture and heritage has made their preservation more important than ever. However, for some Ukrainian Americans, it’s not an unfamiliar position. In fact, it’s the very reason why the University of Rochester holds the Ukrainian Rochester Collection.

A defender of Ukrainian heritage in Rochester

Discover the Ukrainian Rochester Collection

Wolodymr Pylyshenko “understood how fragile a people’s history could be,” says Miranda Mims, the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation. “But he also understood that the value of the materials was in their accessibility.”

- Learn more about the collection, which is open for research use.

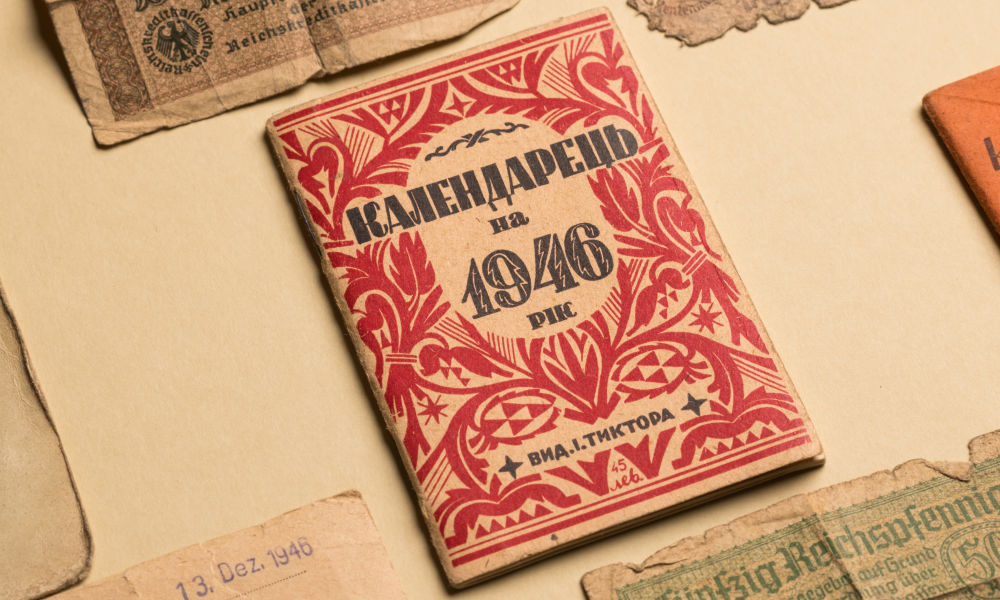

Stewarded by the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation (RBSCP), the Ukrainian Rochester Collection comprises more than 100 boxes of original handwritten documents and published materials, including organization records, club minutes, family papers, memoirs, photographs, and ephemera. Gathered, organized, annotated, and donated to RBSCP by Wolodymr “Mirko” Pylyshenko (1934–2020), the collection is an attempt to preserve the first 100 years of the Ukrainian-American experience in Rochester for the benefit of future generations.

Pylyshenko was born in Ukraine when it was dangerous to be Ukrainian. Persecution by the Soviet Union and the start of World War II forced many Ukrainians to flee their country. During the war, Pylyshenko’s family left their country and spent time living in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and after 1945, displaced persons camps in Germany. Finally, in 1950, he immigrated to the United States with his parents, joining the established Ukrainian-American community in Rochester, New York.

Following his parent’s example, Pylyshenko became heavily involved in the Ukrainian-American community in and beyond Rochester. He was a member and ardent participant in more than two dozen religious, political, social, educational, and professional organizations. And for more than 40 years, he and his family hosted scores of Ukrainian artists, poets, academics, and political figures during their visits to the United States.

Katja Kolcio, one of Pylyshenko’s daughters, recalls waiting for her parents to return from trips to the Soviet Union. Sometimes they would bring back food. Sometimes they would bring back notebooks and other writings from Ukrainian dissidents and political prisoners.

“Ukrainians who fled felt responsible for preserving their country’s intellectual and cultural heritage,” writes Kolcio, an associate professor of dance and environmental studies at Wesleyan University, in a Chicago Sun-Times op-ed. “My parents were among those in the Ukrainian diaspora who did so.”

Pylyshenko worked with people in the community to preserve their family documents. Kolcio says, “When a Ukrainian American died in Rochester, the family knew to bring their mementos to him.” He cultivated an archive of organizational records that speak to all aspects of people’s everyday lives, including politics, religion, professional life, business, sports, education, and intellectual and cultural life. He also encouraged people to write their own stories. All of this is represented in the collection he gave to Rochester.

#ArchivesAreUkraine

Over the past three months, thousands of Ukrainians have become casualties of war. Their stories are potentially lost forever. As Ukraine’s museums and libraries continue to be destroyed or suffer catastrophic damage from Russian fire, collections like Rochester’s become increasingly precious.

Miranda Mims, the Joseph N. Lambert and Harold B. Schleifer Director of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation, discusses the Ukraine Rochester Collection, the department’s relationship with the local Ukrainian community as well as the ones abroad, and her perspective on the value of archives—generally and in times of conflict.

Q&A with Miranda Mims

What do you think is important for people to know about the Ukrainian Rochester Collection?

Mims: The Ukrainian Rochester Collection tells the stories of the people who immigrated to Rochester in the early 1900s and those of their descendants. Individual stories add to the collection’s richness because they hold the names of people who now only exist in the memories of the community members and our archive.

We are so fortunate Mirko had the foresight to actively document and protect his community’s memory. He understood how fragile a people’s history could be. But he also understood that the value of the materials was in their accessibility; he knew it was important for people to be able to engage with their history and understand the meaningful ways Ukrainian-Americans have contributed to Rochester’s development. That’s what you see in the collection he gave to us.

Aside from the massive amount of history that’s been preserved, is there anything particularly noteworthy about the collection?

Mims: One significant aspect is that it is rich with handwritten documents written in Ukrainian. Promoting the collection is important to us, and we want to share it with both the local community and the community abroad, so we are endeavoring to digitize and develop community translation projects. To do this, it is critical for us to develop long-term relationships with the people whose history and culture is represented in this material to ensure we engage in meaningful projects that reflect their vision for their legacy.

Speaking of relationships abroad, the RBSCP has ties to the John McCain Diaspora Library in Dnipro, Ukraine. How did that come about?

Mims: Mirko was instrumental in helping to build the collection held by the diaspora library, which is named for the late US senator and opened in 2019. Working out of the library located within the Ukrainian Federal Credit Union in Rochester, he collected and organized materials that he would send to other libraries here and in Ukraine. It was an extremely meaningful undertaking as some of the material in the McCain collection was once banned by the Soviet government.

I learned about all of this in the summer of 2021, at a celebration for the 30th anniversary of Ukrainian independence here, in Rochester.

Through an existing relationship with Tamara Denysenko, the former executive director of the Ukrainian Federal Credit Union, we began to have conversations with Nataliya Cherneshova (Director of the Department of Economic Affairs, International Cooperation, and Investments), Oleh Repan (Director of the Museum of the History of Dnipro), and Olexsandr Sanzhara (City Council Secretary), who were visiting at that time from Dnipro, Ukraine. During their visit, we spoke about a possible partnership that would make the collection more accessible both locally and abroad.

We are hopeful that we can fully realize this partnership one day. Having the records of a local diaspora community links us to a country in another part of the world and creates a bridge to other diaspora communities dispersed around the world. Having the opportunity to partner with a library such as the McCain Diaspora Library would ensure that the stories we hold here contribute to and are in conversation with the larger story of Ukraine. If we don’t pursue relationship-building and engage with the community, we’ll only ever have part of the story.

This summer, we will begin our first translation project, spearheaded by Lev Earle, our special collections archivist.

According to the International Council on Archives (ICA), “Archives and archivists play an important role in accountability, transparency, democracy, heritage, memory, and society.” What’s your perspective on the value of archives?

Mims: Thanks to the ICA, in June, we celebrate International Archives Day (June 9) and Week (June 6–June 10). Archives can be locally based, but they can also have a global impact, which is why it is imperative that we raise awareness about archives as far and wide as possible. This year’s theme is #ArchivesAreYou.

Archives, by design, are opportunities for understanding and reckoning with the past. However, as our political and cultural circumstances change, so often does the lens through which we interpret historical documents. This is why preserving cultural and intellectual heritage is so important. As archivists and curators, we understand the value of protecting the material culture of the past and making it accessible to people in the present and future generations.

Because you mentioned politics, how does the importance of archiving change in the context of violence, specifically the war between Ukraine and Russia, which President Zelensky has described as an attempt to “[e]rase our country. Erase us all”?

Mims: Material culture is most at risk during times of conflict.

The surviving records that make up the Ukrainian Rochester Collection speak to the complexity of immigrating to America and show how the Ukrainian Diaspora in Rochester came together through shared traditions, family customs, and celebrations of their identity and culture. It represents meaningful contributions and history for generations of individuals and collectives. Imagine that being lost forever.

However, times of conflict are also the times to remember that archives are records of the past.

Contemporary politics is a product of history. Those who focus on what is happening today ignore the long, often complicated series of preceding events, but archives can provide a map through materials like official documents and newspaper articles. Unfortunately, this can make them targets.

Erasure is a tool of oppression. It creates a space that anyone can fill with any narrative they want. Archives defend the past while informing the future.