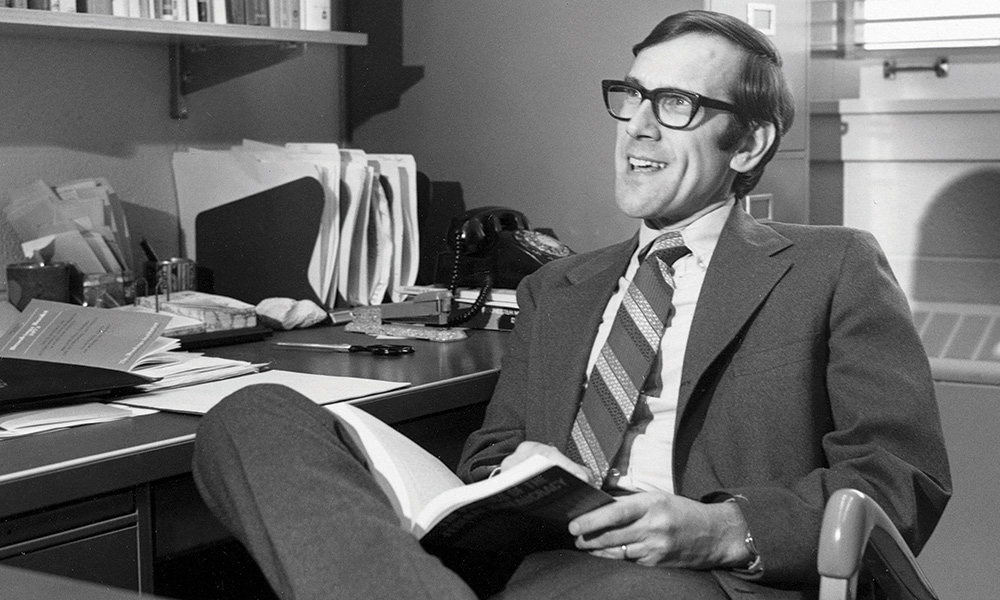

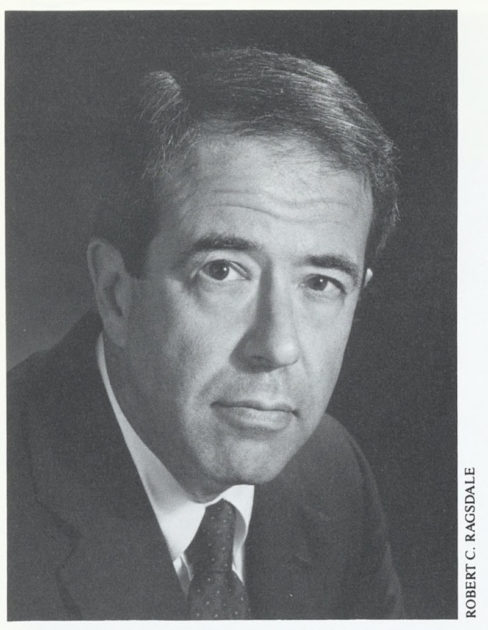

Political scientist Peter Regenstreif is remembered as an expert on mass media.

Faculty, alumni, family, and friends are remembering Rochester political scientist Peter Regenstreif, an expert on Canadian and comparative politics, mass media, and public opinion, who taught at the University of Rochester for nearly half a century.

A scholar, editorial consultant for the Toronto Star, pollster, and consultant to the political campaigns of Pierre Trudeau and Brian Mulroney in Canada and Jimmy Carter in the US, Regenstreif died in Los Angeles on May 19 at the age of 85.

As a professor of political science and Canadian studies in the Rochester Department of Political Science, he regularly taught a very popular course called Politics and the Mass Media. Indeed, the topic had such universal appeal that he regularly gave talks about it outside the classroom:

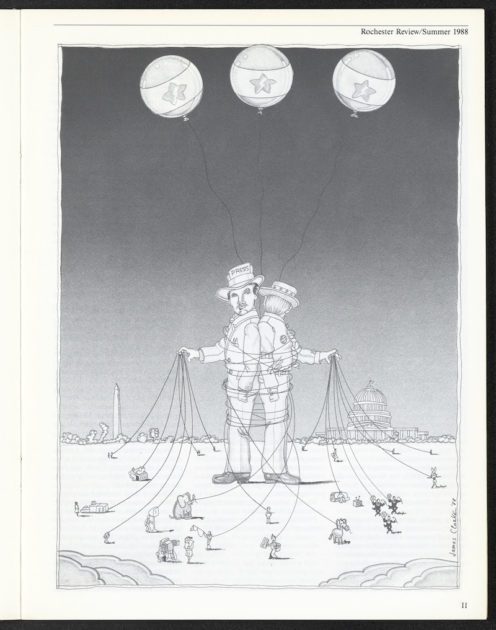

“With the media, there is no truth, there are just appearances,” Regenstreif told a group of Rochester alumni and friends in Boston in 1988.

“The media are sending a message. But who is sending the message via the media? All kinds of people out there: special interests, stakeholders, actors in the arena,” Regenstreif told a group of Rochester alumni in Boston in 1988. A version of the speech was published in the Rochester Review that summer.

In the talk—“A Short Course in the Black Arts of Manipulation,” a version of which appeared in the Rochester Review that same year—he shared the “bald statement” he made every semester to his students: “There is no fundamentally, nonideological, apolitical, nonpartisan, news-gathering and reporting system. Having taken this in, we are ready to understand the process.”

John Mueller, a professor emeritus in political science at Ohio State University who taught with Regenstreif during his own 35-year tenure at Rochester, recalls his friend and former colleague’s “arresting insights,” born out of a deep interest in local, regional, and national politics on both sides of the US-Canadian border. “Peter bounced back between Canada and Rochester. He was very close to the ground; he knew where the bodies were buried,” says Mueller. “He knew how things smelled, which often wasn’t too good.”

Mueller describes Regenstreif as a lively and thoroughly interesting interlocutor—one who married substance with wry humor. What made him exciting to talk to, says Mueller, was how his approach to political science differed substantially from that of many academics—”more practical” and less theoretical.

Despite wearing many hats, Regenstreif knew where his priorities lay, judging from an interview he gave to the student newspaper, Campus Times, in 1973—a good decade after his arrival at Rochester. Calling his other jobs (possibly tongue-in-cheek) “tsoris,” he told the paper that “above all, I’m most valuable as a professor,” adding that “being a professor is a marvelous opportunity to be judged on our merits, rather than on illegitimate criteria. It’s a perfect job for a man who admits that he is very much of an intellectual.”

Regenstreif joined the Rochester faculty in 1961, originally as a research associate while still working towards his PhD in political science and government from Cornell University. Hailing from Montreal, Regenstreif earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and political science from McGill University. At Rochester he rose from assistant to full professor, teaching full time until 1992, when he reduced his teaching to take on more political consulting work. He retired from the University in 2009 to emeritus status.

The symbiotic relationship between politicians and journalists

Regenstreif regularly taught a popular class, Politics and the Mass Media, pointing to the symbiotic relationship between politicians and journalists: “The politicians without the media to spread the word would be helpless. The media without anything to write about would equally be helpless. So they coalesce against us: the politicians using the media to send their message; the media in effect creating a filter for the message—a prism, if you like, refracting the rays into a different direction, a different form, a different coloration for the common man. So where do I, the ordinary citizen, fit in? How can I too use the media effectively? How can I understand what is going on? How can I make sense of these strange and marvelous things that take place almost daily, and—we all feel sometimes—uncontrollably.”

The author of The Diefenbaker Interlude: Parties and Voting in Canada; an Interpretation (Longmans, 1965), he taught some of the largest and most popular courses in the department’s history, including Introduction to Comparative Politics and Politics in Canada, in addition to Politics and Mass Media. That’s where Gary Ciarleglio ’89 first encountered Regenstreif, whom he considers one of his “all-time favorite” professors.An All-American linebacker for the Yellowjackets football team in the mid-to-late-1980s, Ciarleglio graduated from Rochester with a bachelor’s degree in political science. After the team emerged from a multiseason rut, winning the first eight games of the season and beating Hofstra in 1987, Regenstreif reacted with an impromptu speech during class.

“He knew who the football players in his class were,” remembers Ciarleglio, who was also a classmate of Regenstreif’s son Jeff. “It wasn’t a long speech, but he made a point to acknowledge us in front of the class for a job extremely well done and for how it lifted the campus up.”

Regenstreif was always actively engaged with the larger community. The University archive is chock full of notices for talks he gave on campus and beyond, often with provocative titles, such as “The Media and the Presidential Process: Has the System Gone Mad?,” which advertised a public affairs forum in Rush Rhees Library in January of 1988.

Randall Stone, a professor of political science and chair of the department, remembers his late colleague for his “good humor, voluble conversation, and incisive commentary.” Stone tells the story of how, for many years, Regenstreif had been in charge of reading out aloud the names of graduating seniors at commencement: “He pronounced unfamiliar names with impressive boldness, leading students to believe that he had correctly pronounced every name—besides their own.”

Regenstreif is survived by his four children from his first marriage, Anne, Mitchell (Ellen), Jeffrey (Mary Nicole), and Gail (Amy Siadek); his second wife Penelope Temkin, her two children Alexei (Amy DeVoldre Temkin) and Nicole Temkin (Ames Alexander) along with eight grandchildren: Anne’s daughter Rachel; Mitchell’s daughters Nina, Claire, and Grace; Jeffrey’s daughters Julia and Sydney; and Alexei’s sons Ashton and David.