Features

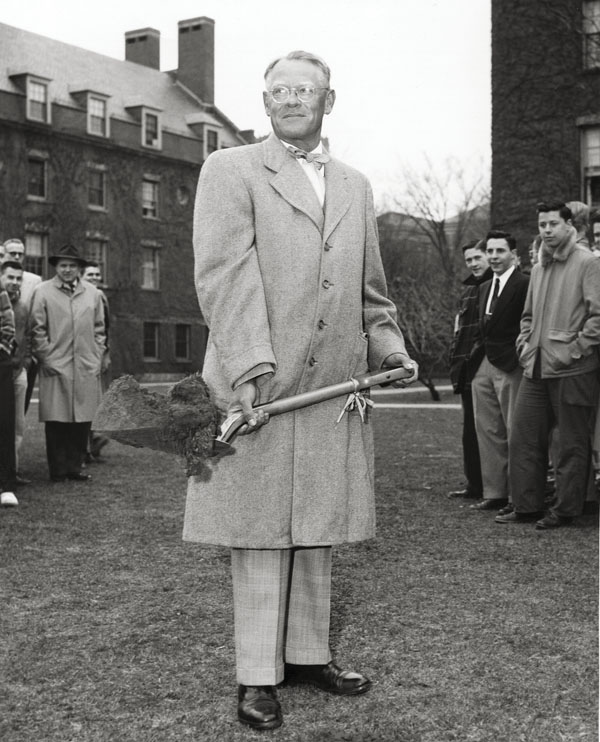

CHANGING PLACES: “A university is never fully mature. It must grow and change, else it languishes and loses its place,” de Kiewiet said when he was named University president. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

CHANGING PLACES: “A university is never fully mature. It must grow and change, else it languishes and loses its place,” de Kiewiet said when he was named University president. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)In 1950, as trustees looked for a successor to Alan Valentine to lead Rochester into its second century, the University had weathered a series of enormous stresses. As a true university it was relatively young. In the three decades since the founding of the esteemed schools of music and medicine—as well as the stately River Campus—University finances, enrollment, and faculty had been buffeted by inflation, the Great Depression, and World War II.

In a sense, the University now faced its first opportunity to plan and define itself—in an era of significant American social change. And it would prepare for unprecedented growth in higher education nationally. College and university enrollments swelled more than 200 percent from 1949 to 1969, much of that growth coming with changing demographics and increased availability of financial aid. Meanwhile, state and federal investment in academic research swelled, particularly when the 1957 Soviet launch of Sputnik heightened concerns about U.S. defense.

At Rochester, projects sponsored by outside agencies became a critical component of ever-growing operations, providing 23 percent of the University’s $26 million budget by 1959. The presidential search committee collected reports from deans and officers as it assessed Rochester’s leadership needs. Among the more serious issues presented: succession plans—or lack of—at the Eastman School of Music and the Medical Center. Both had risen meteorically to premier world ranks, the Eastman School under the groundbreaking guidance of director Howard Hanson, approaching his 30th anniversary; and the medical school under founding dean George Whipple, who, in his 70s, showed little obvious intent to retire. “It is an unsound condition when so much of a school’s success depends upon the presence of a single individual,” provost Donald Gilbert told the committee.

Also, the institution had an “uneven” character to it, treasurer Raymond Thompson observed. While Valentine had set out to place the College of Arts and Science on the same plane of quality as the schools of music and medicine, that had fallen short. Some programs, especially in scientific fields, were heavily funded, leaving little to invest in others. History professor Dexter Perkins “should not have to ‘pass the hat’ for his graduate history fellowship program,” Thompson said. Faculty salaries remained low—lower than prewar levels when adjusted for inflation, estimated at 70 percent from 1939 to 1949.

CLASS OF 1958: Sally Ann Goddard (left to right), Cherry Thomson Socciarelli, June Fundin Hardt, Todne Lohndal Wellmann,

Mary Lind Bryan, and Chrystal Murray were among the first women to study on the River Campus after the merger in 1955. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

CLASS OF 1958: Sally Ann Goddard (left to right), Cherry Thomson Socciarelli, June Fundin Hardt, Todne Lohndal Wellmann,

Mary Lind Bryan, and Chrystal Murray were among the first women to study on the River Campus after the merger in 1955. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)Both the River Campus and the Prince Street Campus needed significant capital investments, especially for the women’s library and gymnasium. In addition, the University would need to examine its expectations of a president. Provost Gilbert told the search committee: “In the modern university the functions of this office have become too manifold to be exercised effectively by a single individual.” The president was expected to be the institution’s academic leader, community leader, involved in national activities, and carry principal responsibility for the growth of University financial resources. An enlarged administrative structure was required, Gilbert said.

By August 1950, search committee members had discussed nearly 150 individuals, looked closely at 70, and interviewed a handful. Trustees Charles Wilcox and Raymond Ball drove to Ithaca to talk with Cornelis de Kiewiet, then acting president at Cornell University. Wilcox recalled immediate, strong enthusiasm: Ball wanted to extend an offer that day.

At Cornell, where he had stepped in as president after the sudden resignation of Ezra Day, de Kiewiet was credited with turning around serious budget problems. Accounts of him described uncommon gusto and a great scholarly and executive mind. If anything, de Kiewiet could run too hard and fast with an idea, a Cornell administrator cautioned the Rochester trustees. De Kiewiet was not always diplomatic, and he was not popular with the Cornell faculty. Wilcox remembered hearing, “He was a Dutchman and . . . the trustees would have to ride herd on him carefully.”

De Kiewiet, a native of the Netherlands, spent most of his early life in South Africa, where his father worked as a railroad construction supervisor. The continent held an important place in de Kiewiet’s intellectual passions throughout his life and factored into a notable push for international awareness during his administrative career. De Kiewiet earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and a PhD in history from the University of London. He accepted an assistant professorship in history at the University of Iowa in 1929, the year he published his first of many eminent studies, British Colonial Policy and the South African Republics, 1848–1872.

De Kiewiet joined the Cornell faculty as a professor of modern history in 1941 and promptly earned leadership roles. During the war years he oversaw language-training programs for the military. He became dean of Cornell’s College of Arts and Sciences in 1945 and provost in 1948. He was in line for the presidency of Cornell when Wilcox and Ball visited.

De Kiewiet shared their eagerness. “The first time that I saw the U of R and its people, I liked the whole spirit and tempo so much that I knew that was the place that I wanted to be,” he recalled. When the Rochester search committee learned the Cornell board would convene October 20, 1950, to name a president, it took the unprecedented step of making an offer before Rochester’s full board could convene for final approval on November 4. “Your committee . . . trusts that the Board of Trustees will recognize the urgency of action that arose,” chair Albert Kaiser explained in a report.

Installed as president the following June, de Kiewiet spoke of the need for ongoing growth in a university. “A university is never fully mature,” he said. “It must grow and change, else it languishes and loses its place.” This conviction, he said, applied to the three main activities a university supports: to pursue knowledge wherever it may lead; to cooperate in the technological process that advances business and industry; and, most important, to relate both knowledge and technology “to man’s quest for dignity, peace, justice, the good of life—all the qualities and aspirations which make man a spiritual as well as a physical being.” As the 1951–52 academic year opened, de Kiewiet announced the creation of the University’s first office of development, headed by former provost Gilbert. It was the first in roughly a dozen major new administrative posts, and it would support efforts on many fronts.

De Kiewiet shared candid thoughts in retirement that shed light on his decisions through the transformative period. He participated in an oral-history interview with a University public relations officer in 1971. In the early 1980s, he submitted a poignant draft of an essay for a planned, but never published, University of Rochester Library Bulletin on presidential recollections.

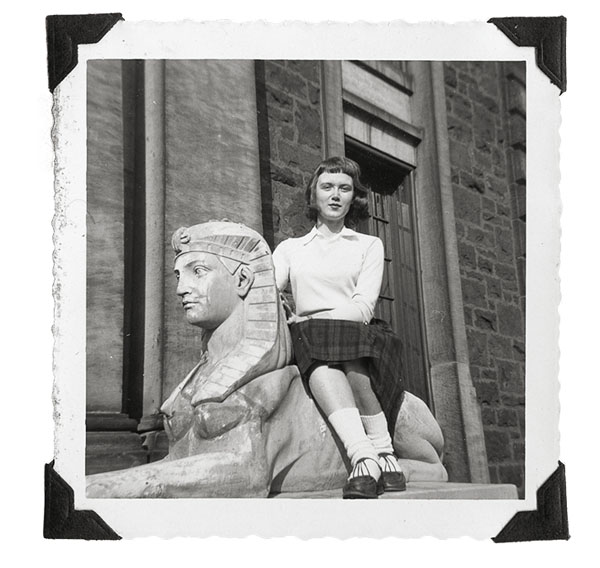

ICONIC MOVE: Sylvia Weber Masucci ’58 poses on one of the Sibley Hall sphinxes, Prince Street icons that, along with a statue of first president Martin Anderson (below), were moved to the River Campus as part of the merger. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

ICONIC MOVE: Sylvia Weber Masucci ’58 poses on one of the Sibley Hall sphinxes, Prince Street icons that, along with a statue of first president Martin Anderson (below), were moved to the River Campus as part of the merger. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation) (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

(Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)Reflecting on his early impressions of the University, de Kiewiet described an “absence of any sense of wholeness, from which the University suffered grievously.” The women’s Prince Street Campus was five miles away from the men’s campus. The administration operated from a residential block there. The Eastman School was downtown in a neighborhood suffering some decay. The medical school, though near the River Campus, also seemed disconnected. “The closest that I feel entitled to come was that each constitution was conceived and considered in its own right,” de Kiewiet remembered. He worked throughout his 10-year term to form a cohesive University “silhouette.” De Kiewiet immediately questioned the logic of a separate women’s campus, which, with some buildings nearing 100 years old, would need $4 million in updates. Faculty and students wasted time, the president believed, traveling between the campuses for various courses or facility use. Further, the arrangement implied inequality for women. De Kiewiet sounded out his idea—transferring women to the River Campus—with board chair M. Herbert Eisenhart.

This notion, though sometimes raised in prior years, had never been considered seriously. There were strong traditions and attitudes. The venerated Rush Rhees, president when benefactor George Eastman led contributions toward development of the River Campus, believed in coordinate education for men and women. Rhees also had wanted to preserve the University’s first campus, opened in 1861. Alumni and alumnae held strong sentiments for their respective colleges, and there was considerable opposition to coeducation among River Campus men who believed the presence of women would cause a drop in academic quality.

De Kiewiet recalled, 30 years later, the powerful impact of his private talk with Eisenhart in the chair’s home. “Mr. Eisenhart was a man of great politeness and attention. He heard me patiently for two full hours. Then he arose to put a glass of whisky in my hand. Then he said with real kindness: ‘I am happy to have listened to you, and I would like to give you some advice. Outside this room, never mention again the idea of bringing the men’s and women’s college together.’ I finished my drink speechlessly, and felt like a marathon runner who falls over at the beginning of the race. On my way home, I remembered what I had said, and the enormity of what had been said. I recalled standing on the verandah of the administration building, and seeing nothing around me. My resolution was like a physical sensation. I would go on and talk, or would go away.”

That November, the president told the board’s executive committee he intended to study “the financial and academic justification” of maintaining separate colleges for men and women. The next month, he reported to the full board on the cost of improvements to the women’s campus—and the national trend toward coeducation. By January 30, 1952, de Kiewiet could report that after consultations with faculty, students, and Rochester graduates, he believed a college merger would have support.

Student opinions were mixed. “I feel it would lower our school’s standing,” Arthur Bernhang ’55 wrote to the Campus. “At present we do not lack social contacts with women, and if they were in our classes it would be distracting.” Bob Gordon ’52 raised a counterpoint: “[It is] necessary financially as the women’s campus is definitely falling behind and needs major improvements. Co- education would be nice and I don’t feel it would have any bad effect on marks. We’d also get rid of the inter-campus transportation problem.”

ICONIC HOME: Construction on a residence hall for women began in the early 1950s (above) in preparation for the move of the women’s college to the River Campus. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

ICONIC HOME: Construction on a residence hall for women began in the early 1950s (above) in preparation for the move of the women’s college to the River Campus. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)On April 26, 1952, the Board of Trustees unanimously approved that the two colleges “be consolidated at the earliest possible moment.” A cost comparison had been compelling: the women’s college would need $4 million in facility improvements and $10 million to endow program expansion; estimated merger costs were $8.6 million. Said board member James Gleason, a Rochester manufacturer, “Women are taking an increasingly important part in the industrial and professional life of the Nation. This move is in the spirit of the times.”

“Rochester Adopts One-College Plan,” the New York Times announced April 30. The news became bigger: That fall, the University kicked off a $10.7 million capital campaign, with $4 million planned for construction of women’s dorms; upgrades to the student union (Todd Union); and new buildings for the administration and University School, the community education division. The remaining $6.7 million would support faculty recruits and salary increases, scholarships, and student services. Donations ultimately lagged by at least $2 million—a symptom of Rochester’s ongoing struggle with perceptions of its wealth as the principal heir to industrialist Eastman. De Kiewiet preferred the term “integration” to “merger.” In his annual report for 1951–52, he explained, “Rochester is seeking an integration of many parts into a structure that will retain the elements of its present form but welded into a new shape that will be stronger, more active, more effective in the educational life of the community and nation.”

Rochester committees examined a range of matters in the years leading to the merger—admissions, accounting, curriculum, dining, student services, and preservation of meaningful artifacts from the historic Prince Street site. Most important, the merger would present an opportunity for the University to reexamine its role. “The merger gives us an opportunity to begin with a clean slate, to develop anything we desire and determine,” officials wrote in a grant application for self-study in October 1952.

De Kiewiet envisioned an entirely different kind of institution. He referred to a new “center of gravity” for the University. Higher education already was forever changed—in part due to sheer growth in the number of students after the war; in part due to changes in research influenced by the Manhattan Project and other wartime endeavors. Referring to a popular concept then of Rochester as being on par with prominent undergraduate colleges such as Amherst, the president recalled, “I came with a different point of view as to where the most effective center of gravity of the American university system might be or should be, and that clearly was upwards a distinct notch in the direction of more professional education, more graduate education, more research, more of a relationship to the whole phenomenon so much stressed by the Manhattan Project of scientific and intellectual investigation and research.” He also wanted the University to benefit from a close relationship with the prestigious—but decidedly independent—schools of medicine and music.

Distinguished scholars were hired: Vera Micheles Dean in international studies; pioneering political scientist Richard Fenno, the Don Alonzo Watson Professor of History and Political Science; and economist Lionel McKenzie, the Marie C. Wilson and Joseph C. Wilson Professor of Economics. The University drew worldwide acclaim for physics professor Robert Marshak’s annual organization of the International Conference on High Energy Physics, commonly known as the “Rochester Conference.”

There would be difficulties. Some faculty complained of “second-class” treatment compared with research scholars. De Kiewiet’s efforts to exert stronger influence in music and medicine met resistance. Hanson, according to Eastman School historian Vincent Lenti, criticized: “The new president’s policy . . . called for a strong centralization of authority in the university administration, the final authority resting with the president and filtering down to the deans through a series of vice-presidents, provosts, and other university officers. Coupled with this was his insistence that the central core of the university should be the College of Arts and Sciences. Under this policy the College of Arts and Sciences became, itself, the university, the rest of us being adjuncts of the main body. Fortunately for us, the Eastman School was located in downtown Rochester, four miles from the River Campus, and our physical separation kept us from being entirely drowned in the Genesee.”

COMPUTER AGE: The University established its first computer center with a single desk-sized machine in 1955. The center was

upgraded a year later and again in 1961 to keep pace with changing technology. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

COMPUTER AGE: The University established its first computer center with a single desk-sized machine in 1955. The center was

upgraded a year later and again in 1961 to keep pace with changing technology. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)De Kiewiet’s style may have estranged some. Soon after arriving at Rochester, he sent letters to national medical educators requesting names of a potential dean to replace Whipple—before realizing Whipple had not yet decided to retire. On another occasion, de Kiewiet apologized to trustees for publicly announcing key administrative appointments before sharing the information with the board. In a letter to Whipple’s successor, Donald Anderson, de Kiewiet seemed to explain his sense of urgency: “A president has three years for innovation, three years for consolidation, and three years for loss of reputation.” At least two deans resigned over differences with the president, and a Middle States accrediting committee raised a concern about lack of communication between the University administration and Medical Center leadership. “President de Kiewiet soon became a controversial figure at the University of Rochester,” longtime chemistry chair W. Albert Noyes Jr., the Charles Frederick Houghton Professor of Chemistry, wrote in a memoir. Noyes served as graduate studies dean and, temporarily, dean of the College. “But, I can honestly say that I have never served under a university president with a better . . . understanding of the essentials of a good university.”

Noyes helped gain faculty support for de Kiewiet’s second organizational feat: to create the professional schools of education, business, and engineering in 1958. The president saw these disciplines as anomalies in the College of Arts and Science that probably were not adequately supported in that liberal arts context. Demand was high for professional courses; part-time enrollment for employed adults in the community education division—known as University School—increased from 2,800 in 1954–55 to 4,300 in 1957–58.

A faculty committee examined options for two years before recommending the plan to develop the new schools. Rochester’s industrial leaders had pressed for engineering expertise. More broadly, knowledge was expanding and subdividing in specialties, and the United States had become a world center for training, de Kiewiet told the board. “U. of R. Raises Its Sights,” an editorial headline in Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle declared after the University’s announcement of its new divisions. “The reorganization, in time, will change the profile of the university, physically, as higher enrollments, more facilities dictate expansion,” the article said. “The inner change will be felt even more because it is indicative of the U. of R.’s resolution to meet the new, titanic challenges of higher education.”

John Graham Jr., vice president of the Cooper Union, was recruited as dean of the College of Engineering. Previously he rose from instructor of civil engineering to dean of students at Carnegie Institute of Technology, later part of Carnegie Mellon University. By 1963, Rochester’s engineering school faculty doubled to more than 30, and sponsored research grew from $20,000 a year to $375,000. Doctoral programs were begun in mechanical and electrical engineering— chemical engineering already had offered a PhD. In 1960, the engineering college, working with the Medical Center, added one of the first biomedical engineering degrees in the country.

John Brophy, a professor specializing in organizational theory and administration at Cornell, was appointed dean of the School of Business Administration, later the Simon Business School. During Brophy’s five-year tenure, full- and part-time MBA programs were established. Charles Plosser, a former dean of the school and the Fred H. Gowen Professor of Business Administration and the John M. Olin Professor in Government, credited Brophy with setting the foundation for one of the country’s leading business schools.

William Fullagar, the Earl B. Taylor Professor of Education Emeritus, served as founding dean of what became the Warner School of Education. Under his leadership from its inception in 1958 until 1968, faculty increased more than fivefold, to 37. Enhanced graduate programs, including doctoral degrees, drew 141 full-time students and 482 part-time students in 1968. The president would report at the end of the 1958–59 year, the first of operations for the new schools: “It is not customary for an institution of higher education to create in one year three new, major educational units. Yet it seemed after mature and protracted reflection on the part of all concerned that the University in terms of the purposes it had set for itself in the anticipated dynamic period of the 1960s should complete the reorganization of its academic structure in one move and thus be as adequately prepared as possible for the demands which it was clear would be placed upon it.” Harper’s Magazine in 1959 identified the University among several whose distinction was greater than recognized, de Kiewiet told the board.

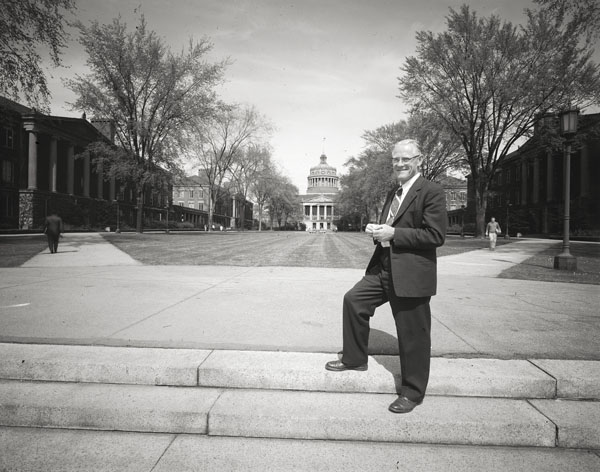

NATIONAL PICTURE: Taking a prominent national role, de Kiewiet was president of the Association of American Universities and

the American Council of Learned Societies. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)

NATIONAL PICTURE: Taking a prominent national role, de Kiewiet was president of the Association of American Universities and

the American Council of Learned Societies. (Photo: University Libraries/Department of Rare Books, Special Collections, and Preservation)University historian Arthur May described the creation of the three professional schools as “the most significant development in the University complex since the opening of the Medical Center more than three decades before.” The separate units would enhance training for local industries and be in a better position to attract growth capital, May said. A Rochester Review report marking the schools’ 50th anniversary noted de Kiewiet wanted the units to have more autonomy to pursue their academic development and programs. Also, putting the divisions on a new professional and graduate level would better position them to attract faculty and students. “The moves also bolstered Rochester’s position as a research university made up of academic units devoted to particular fields,” the Review said.

A new sphere of demands began to surface. Students became more critical of University administration. Student newspapers of the 1950s show the beginning of familiar complaints about tuition, parking, and dining. Tuition more than doubled from 1951 to 1961, to $1,275. As automobile use increased—it doubled in the Rochester metropolitan area from 1946 to 1956, to 200,000—the University revised its parking policies and imposed fines of $40 or more for violations. When the University instituted a compulsory board plan in 1959, letters streamed to the Campus-Times, the newspaper formed after the merger of the men’s and women’s campuses. “Meals are obligatory now for the simple reason that if this were not the case, few would be foolish enough to pay for them,” wrote A. Lapidus ’60. “There are few people who, if faced with a choice between lime [Jell-O] and cottage cheese on lettuce with Russian dressing, and a good steak dinner for under a dollar in one of the restaurants which surround the campus, would not choose the latter. The fact is that the food bought by the University is bad and the preparation is worse.”

Students became more active around deep social concerns, most evident when racial tensions grew in the South. At least 50 students picketed the downtown Rochester Woolworth’s in March 1960 to protest the retail chain’s policy of lunch-counter segregation in the South. “The act signals a revival of consciousness in a generation,” stated a Campus-Times editorial. “Those students and few faculty members who silently and anonymously walked back and forth in front of Woolworth’s for two hours last night in freezing cold, those people generated their own warmth.” About the same time, student members of the NAACP demanded University pressure for removal of a clause in the charter of national fraternity Sigma Chi prohibiting membership of nonwhites.

A History But Begun ...

The history of the University is getting an update.

Our Work Is But Begun: A History of the University of Rochester, 1850–2005, by Janice Bullard Pieterse, a freelance writer in Rochester, is scheduled to be published this fall by the University of Rochester Press.

With a foreword by President Joel Seligman and an afterword by Paul Burgett ’68E, ’72E (PhD), University vice president and senior advisor to the president, the book takes the story of Rochester through the tenure of the University’s ninth president, Thomas Jackson.

The main narrative focuses on Rochester’s leadership, direction, and goals, but the book is filled with sidebars, profiles, and anecdotes of academic and student life at Rochester over the past 160 years.

The new book takes its place among other historical accounts of Rochester, including A History of the University of Rochester, 1850–1962, by the late Rochester professor Arthur May (Princeton University Press, 1977), Beside the Genesee: A Pictorial History of the University of Rochester, by Jan LaMartina Waxman ’81N and edited by Margaret Bond ’47 (Q Publishing, 2000), and Transforming Ideas, edited Robert Kraus ’71 and University Professor Charles Phelps (University of Rochester Press, 2000), both published to coincide with the University’s sesquicentennial celebration in 2000.

Our Work Is But Begun will be available to pre-order on the bookstore’s website (http://urochester.bncollege.com) beginning in August. Updates on ordering the book will be posted on the bookstore’s Facebook page at http://www.facebook.com/URBookstore. Questions about orders can be directed to (585) 275-4012.

By the end of the decade, it was time to look again at development. De Kiewiet drew up plans for the next phase of University growth—new dorms for men; a wing for physics, optics, and math; a science lecture hall and other academic buildings; and a chapel. The Medical Center, undergoing its own reorganization under the leadership of Anderson, was enhanced by an expanded library, new buildings for the Atomic Energy Project, animal studies, and hospital facilities. The College aimed for enrollment growth of 25 percent, to 2,500. With 4,100 employees—including nearly 500 full-time faculty members—the University ranked sixth largest among Rochester employers.

“The nation’s need for educated manpower is rising sharply and will continue to rise,” de Kiewiet said. “The explosion of new knowledge in our time is unparalleled in world history. International crises on every hand require creative solutions to new and age-old problems.” “A university must have and show a dynamic attitude to its own future,” de Kiewiet said.

But de Kiewiet was becoming restless. His correspondence with board members showed frustration, especially on financial issues and control of the music and medical schools. He saw an ally in the newly elected chair, Joseph Wilson ’31, founder of Xerox Corp. Wilson would be a significant figure through the 1960s. In the summer of 1959, de Kiewiet raised privately with Wilson the prospect of moving the Eastman School to the River Campus. “I am aware that this sort of thinking may light fires from horizon to horizon,” de Kiewiet said. “I am aware also that it may turn out to be completely unrealistic, but I am also aware, and this is important, that the total financial picture of the Eastman School of Music is going to call for some very radical handling.” Evidently stunned, Wilson replied, “The idea . . . was so new to me that I will refrain from doing more now than to say that I will think about it thoroughly.”

Within months, de Kiewiet would write of worsening malaise. “The combination of a tug of war between the executive and finance committees and of the lack of any clarity of responsibility in the Board of Managers of the Eastman School of Music have made me feel that my sense of unhappiness can only increase.” Six months later, on news that his daughter was terminally ill, de Kiewiet requested a leave of absence. He resigned in the summer of 1961.

Historian Richard Glotzer credited de Kiewiet with helping shape the research university as it is known today. “At Cornell and Rochester, de Kiewiet recognized the urgent need for change in post-war universities,” Glotzer wrote in an analysis published in American History Journal. “He understood that the jerry rigged arrangements hurriedly grafted onto pre-war university structures were ill-suited to sustain an ongoing explosion of knowledge and technology.”

De Kiewiet was a force on the state and national level. In New York, de Kiewiet led a council of private colleges and universities to consult with legislators forming the state university system. He served as president of the Association of American Universities and of the American Council of Learned Societies, where he defended universities under scrutiny during the McCarthy era and articulated the importance of funding higher education as its services grew. De Kiewiet also served a variety of national roles as the U.S. government and grant-making organizations looked for ways to understand developing nations and support their educational institutions, including South Africa. The president sent farewells to several trustees. He wrote to Eisenhart: “There is, of course, sadness in leaving an institution where we both worked with a sense of purpose that lay beyond ourselves even though perhaps sometimes my own hand reached too far. It always takes time for perspectives that have been rudely broken to re-establish themselves but I take comfort in the conviction that this decade has been useful.”

He closed a letter to trustee Sol Linowitz, Wilson’s business partner: “All men must be measured finally by the direction and the distance of their gaze. I am content to be measured by this test.”

This essay is adapted from Our Work Is But Begun: A History of the University of Rochester, 1850–2005 (University of Rochester Press, 2014). Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.