Features

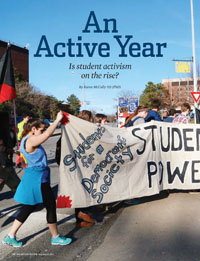

BLACK LIVES MATTER: “It’s important that we talk about our experiences, and why this matters,” says Green, an organizer of the November 25 march (above) who traveled to Ferguson, Missouri, last fall. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

BLACK LIVES MATTER: “It’s important that we talk about our experiences, and why this matters,” says Green, an organizer of the November 25 march (above) who traveled to Ferguson, Missouri, last fall. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Amber Baldie ’15 remembers exactly where she was when she heard the news that Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson would not be indicted in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown.

“I was in the IT Center,” she says. It was just after 9 p.m. on the Monday evening before Thanksgiving, and a small gathering of students stood by the flat screen television affixed to the Gleason Library wall, scrolling on smartphones, waiting for the grand jury decision, which had been expected for days.

“When the announcement came,” Baldie says, “I just broke down and started crying.”

It had been a long and anxious wait. Baldie, a statistics major from Gates, New York, and several of her friends had spent the weekend making signs, in anticipation of a decision they feared wouldn’t go the way they wanted. So when St. Louis County prosecutor Robert McCulloch rose to the podium to announce the grand jury decision, the news was not entirely a surprise. And yet still, it was a shock. Reflecting on that moment, several months later, from the living room of the Douglass Leadership House on the River Campus Fraternity Quad, Baldie confides, “We still did have a little bit of hope.”

When Baldie walked out of the IT Center, and onto the platform where students gather to await buses and shuttles, she carried a sign with the words “Hands Up. Don’t Shoot.” As she and her friends stood with their signs, they were joined by others, and within a short period of time, a crowd had gathered. The demonstrators stood in a circle, holding hands, as Natajah Roberts ’14 came forward and began leading the group in chants. The participants in the spontaneous gathering marched across the River Campus. Then they headed up Elmwood Avenue to College Town. “That’s when we felt this momentum,” Baldie says.

The momentum was felt nationally. That same moment, protests were erupting in more than 180 cities, and on college and university campuses, around the nation. The demonstrations on the evening of November 24 had been so swift, so coordinated, and so national in scope that mainstream news media outlets began referring not merely to the Ferguson protests, but to a movement—a new civil rights movement, reacting to police violence against black Americans and organized around a simple declaration: Black Lives Matter.

But November 24 was less the beginning of a movement than a turning point, both nationally and in Rochester, where students and recent alumni had already launched a new community organization, BLACK: Building Leadership and Community Knowledge.

The previous August, when news broke of the fatal shooting of Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old black teenager with no criminal record, protests erupted immediately in Ferguson. And Baldie, Makia Green ’14, and Anansa Benbow ’15 started texting.

“Our hearts were heavy,” says Green, a psychology major from New York City who was returning to campus for her final semester. They’d been following events closely on Twitter. News outlets told one story, while people on the ground in Ferguson told another. “We started hearing their stories,” Green says of Ferguson residents. “And it was affecting us. About that time, Anansa, Amber, and I had a conversation about what we could do.”

Baldie, Benbow, and Green, who graduated this academic year, had been friends from their first days in Rochester. They’d held the presidency of the Douglass Leadership House, the Black Students’ Union, and the Minority Students Advisory Board, respectively. Green and Baldie were active in theater. Benbow was part of Students for a Democratic Society. All three women had won major awards for their contributions to the campus community. And they’d reached beyond the campus as well, joining local community groups such as Metro Justice.

When they arrived back on campus, they met with Roberts, then an organizer for the Service Employees International Union, and Adrian Elim ’13, a native of Rochester’s 19th Ward, and a cofounder of the Rochester multimedia design and production company Brothahood Productions. The week before school started, the friends tapped into their local networks, calling for a meeting to be held at the Flying Squirrel Community Space on Clarissa Street.

The site was significant. “Clarissa Street used to be a very prominent black area before Urban Renewal,” Elim says, referring to the federally subsidized demolition of many city neighborhoods, throughout the United States in the 1960s. Clarissa Street was the heart of black Rochester, with a bustling mix of stores, clubs, and doctors’ and lawyers’ offices. Today, though it’s home to three churches, it’s otherwise a sparse mixture mostly of garden apartments. “We really wanted to pay homage to that energy that used to be there.”

About 60 people turned up at the Flying Squirrel on the evening of September 12. It wasn’t immediately clear what would grow out of it. “We were all emotional,” recalls Roberts. “It really was a major moment of mourning in the black community.” But as Roberts, Baldie, Benbow, Elim, and Green facilitated the gathering, it became clear, says Roberts, that more was at stake than combatting police violence against people of color. “We were a group of a lot of young people of color, gathered in a room, who cared about the black community. And there wasn’t already a group like us.”

Rosemary Rivera, a local activist, met the five young leaders for the first time that night. “They captured the attention of many of us who have been doing this for ages, way before Mike Brown,” she says. The city’s activist community had aged. “When you’d go to rallies, you’d see the same people.” They needed new and younger energy. Rivera recalls feeling “overjoyed.”

Out of the meeting came BLACK. The name is both a clear statement of racial pride and identity, and an acronym for Building Leadership and Community Knowledge, a phrase that sums up the aims of the group, whose members refer to it as a grassroots collective. In the 10 months since Baldie, Benbow, Elim, Green, and Roberts founded BLACK, the group has established a reading group; held film screenings; developed a program for volunteers to walk children to school; established an after-school tutoring program at the Monroe County Public Library branch on Arnett Boulevard; planted the Causing Effects community garden; established an ongoing social media campaign featuring local, black-owned businesses; held a black-owned business workshop; and passed out T-shirts and buttons such that, on any given day, walking down the tree-lined streets of the 19th Ward, you might see someone affiliated with the group.

When BLACK got under way last fall, one of its first initiatives was to send its own delegates to Ferguson for a four-day “national call to action.” In early autumn, Ferguson was emerging as a training ground for community organizers. Rivera and another local activist, Ricardo Adams, traveled to Ferguson shortly after the founding of BLACK, and when they returned, strongly urged the young Rochester leaders to make a trip there as well. Through BLACK, Green, Benbow, Elim, and Roberts launched a crowd-funding campaign to finance their trip. And over a long weekend—one that Benbow notes fortuitously coincided with Arts, Sciences & Engineering’s fall break—they drove 13 hours to Ferguson to participate in the series of demonstrations known as Ferguson October.

Benbow, a linguistics major from Troy, New York, and Green prepared for the trip as though it were a high-stakes exam. “Makia and I had been watching the livestream every night for two weeks straight. We had been finding people on Twitter to follow, and reading a lot of articles,” Benbow says. Rivera and Adams put them in contact with Ferguson activists who agreed to be their hosts. For four days, they participated in sit-ins and marches. They saw the military tanks, helicopters, and riot gear. They got arrested on the charge of unlawful assembly, and they were jailed along with protesters, many of them also college students, from around the country.

“We realized the power that college students have,” says Benbow, noting the national media spotlight that shone on Ferguson during the four-day event. Benbow and Green both say they were subjected to excessive force—struck by fists and clubs, and pulled by their hair. But Benbow thinks things would have been worse had they not been college students, and from out of town.

“Being college students and not being from there, I think we were treated differently. It would have been different if we were all just black people from Ferguson.”

Benbow is forthright when she says Ferguson was “like a war zone.” But beneath that, she found community roots that she believes are stronger than many people outside Ferguson realize. “What I think a lot of people miss about the community down there is the foundation of love. It caught me off guard a bit.”

Benbow, Elim, Green, and Roberts left Ferguson prepared to bring their stories back to Rochester, and to put what they’d learned about community organization into action.

For Benbow and Green, the transition back to campus was difficult. They were bruised, emotionally as well as physically, and talking about the experience could be disheartening. Green recalls conversations on social media, in particular, in which she and her friends were deemed “overdramatic,” and “a nuisance.” But they were persistent. They drew strength and support from friends, including staff members at the Paul J. Burgett Intercultural Center and the Office of Minority Student Affairs. The week before the grand jury announcement, Green, Benbow, Baldie, and Alexandra Poindexter ’15, a political science major from Lawrenceburg, Indiana, and then president of the Black Students’ Union, held a die-in in Wilson Commons.

“It was nerve-wracking,” says Benbow. On a Friday afternoon, a time of heavy traffic in the student center, they put up caution tape and lay on the ground. They’d arranged for speakers, including a slam poet. Benbow recalls people gathering, on the balcony and on the stairs, watching, and listening.

The next week was a turning point. The day after the grand jury announcement, the students organized a demonstration at the entrance to the River Campus on Elmwood Avenue. Publicizing the event on campus and through BLACK, they drew students, faculty, staff, administrators, and members of the community.

It was an organizational feat, and one in which Green, Benbow, Roberts, and Elim drew heavily on their experience in Ferguson. With Baldie, Poindexter, and others, they worked in concert with the University’s Department of Public Safety. They dispersed throughout the crowd to keep it focused, peaceful, and on message. They traded turns leading the group in chants. Green served as spokesperson, taking interviews with local news outlets, explaining what the demonstration was about, and what protesters meant by the deceptively simple slogan Black Lives Matter.

Through BLACK, the leaders were establishing a presence around the city. The group organized a downtown rally that attracted some 500 people. In the weeks and months ahead, students, including members of BLACK, held events on the River Campus every Friday—“Ferguson Fridays”—organized around the theme Black Lives Matter.

During all this time, BLACK continued to build itself up in the 19th Ward, and to flesh out its programming and philosophy.

The 19th Ward, just across the Genesee River from the University’s main campus, is a neighborhood in which middle class, working class, and poor residents intermingle. But many of the people who call the 19th Ward home, especially its predominantly black youth, Elim says, have absorbed negative images about black life and culture. In July, the group will launch a new initiative called “I Define Myself.” Elim paraphrases a quote from Audre Lorde. “She said, ‘If I do not define myself for myself, I’ll be crushed into other people’s fantasies of me and be eaten alive.’ And that’s a really important point for our youth.”

Elim claims among his heroes not only Lorde, but James Baldwin and Bayard Rustin, two black activists who were also, like Lorde, gay. He does it to underscore a central tenet of Black Lives Matter. Elim stresses that all black lives matter.

“When we say Black Lives Matter, we mean black LGBT lives matter, the lives of black women matter. We have to come together as a community and take a look at all the nuances of what it means to be black.”

BLACK, he says, is “a lifestyle. It’s not a job or an extracurricular activity. We’re talking about changing habits.”

Since the beginning of BLACK, Elim says, he’s changed a few of his own habits. He pays attention to where he spends his time and his money, supporting black artists and black businesses. The group is rooted in a long tradition of black community uplift, stretching back a century, to Marcus Garvey, and to the 1960s, with Malcolm X. The founders of BLACK have added their own twist.

On Facebook, BLACK declares itself “rooted in the minds and spirits of the U of R and the 19th Ward.” BLACK is Meliora brought to bear on the tradition of black empowerment and community self-reliance.

“We want to build a self-sustaining structure,” Elim writes in a Facebook message. “We are here for the long haul.”